|

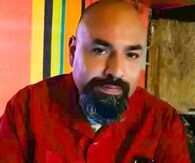

Rinconcito is a special little corner in Somos en escrito for short writings: a single poem, a short story, a memoir, flash fiction, and the like. Two poems by Vincent CooperVeterano Before the election I saw Chicano veterans holding up Vote for Trump Signs outside of schools And libraries. Some Veteranos Don’t know they’re Chicano, They want that towering wall Dividing America and Mexico To smite gay pride and the rainbow flag. Trump-sates the blood-thirsty hate from within The void of my father Was filled by a Veterano, Who in 1967 (Dropping out of Brackenridge High School) Heard the war song of A westside Marine Corps Recruiter. “Go defend our country son make Uncle Sam proud. Don’t worry about a High School Diploma, You’ve got the Viet Cong to think about. You’ll be physically fit, cock strong, in your dress blues All these westside chicks are gonna want to fuck you You’ll have medals pinned on your chest, a career as a cook or custodian Benefits with a steady paycheck, a cheap little house with an iron fence C’mon be a real man with a rifle in your hands And tell them all, later on, about the young heroes of war Jungle sounds, Khe San and how things were in’ Nam. Vietnamese rats Chasing like rabid dogs So large you couldn’t swallow Shooting women And children Coming back To be a Little League coach For your kids- A hero? A patriot? Wearing a red and gold cover That reads: 1967-1969 Reconnaissance USMC Raising a Devil Dog flag in the front yard Next to an American flag. Everyone driving by knows where you stand. Who you are A Veterano What you did For this country That is not yours A dream you’re not in. A Real Marine You’re a marine? Thank you for your service is physically fit, says OORAH when they see another marine, has American pride, honors the eagle, globe and anchor, has a bulldog named Chesty, tells war stories, while polishing his medals, banks with USAA, psycho tough, ready to kill, never hesitates, knows martial arts like Chuck Norris, is an alcoholic with a side chick, has PTSD, a racist in denial, attends air shows with the silent drill platoon. A real marine says this country has gone to shit, doesn’t want to die, because their grandson is gay, on the flip, he wants gays in the military to serve as bullet-catchers. A real marine gets shafted by the corps, years later, thankless service, wearing a red cover, USMC t-shirt, won’t stop until the job is done, flashbacks, hates Asians, haircut high n’ tight, originally from Parris Island, is sometimes a tio taco, not that amphibious, a cock boy in dress uniform, marching at grocery stores. A real marine trains people of color to kill people of color. A United States fucking Marine, trained to kill anyone, anything, even himself. I didn’t go to war.  Vincent Cooper is the author of Zarzamora – Poetry of Survival and Where the Reckless Ones Come to Die. His poems can be found in Huizache 6 and Huizache 8, Riversedge Journal, and Latino Literatures. Cooper was selected to the Macondo Writer’s Workshop in 2015. He currently resides in the southside of San Antonio, Texas.

3 Comments

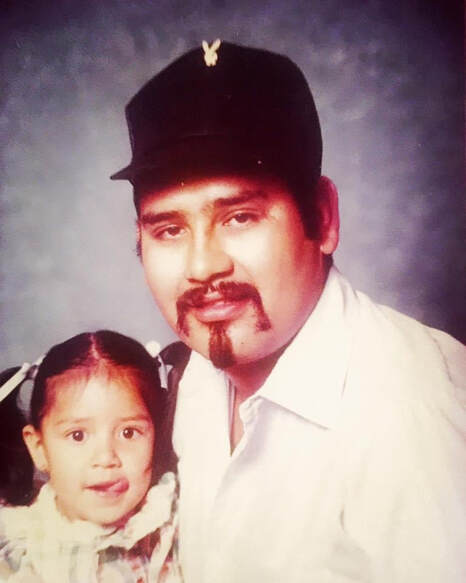

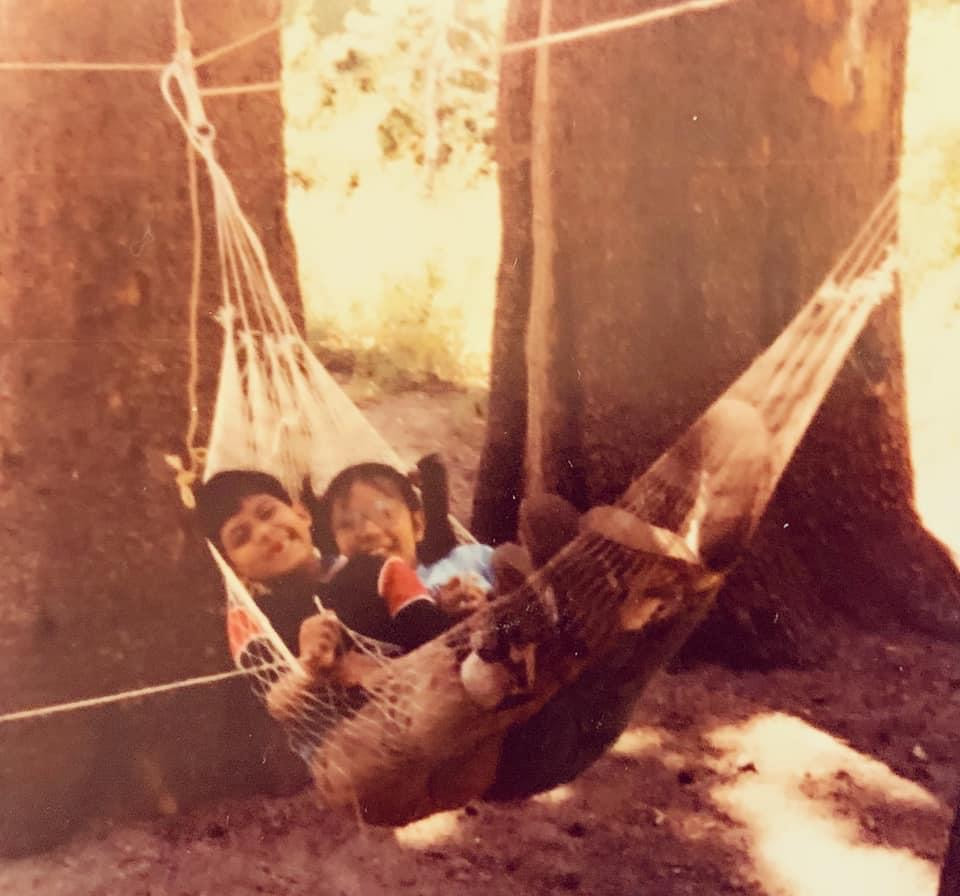

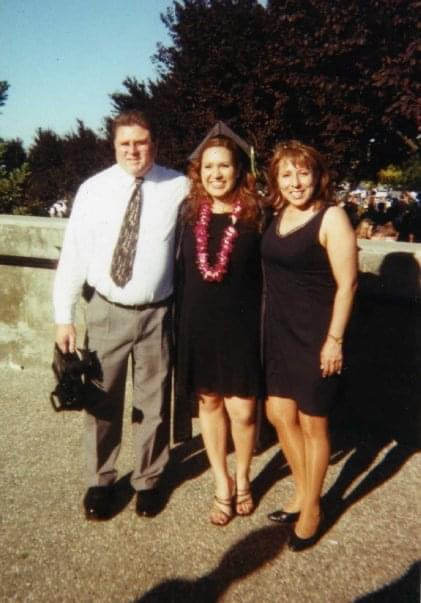

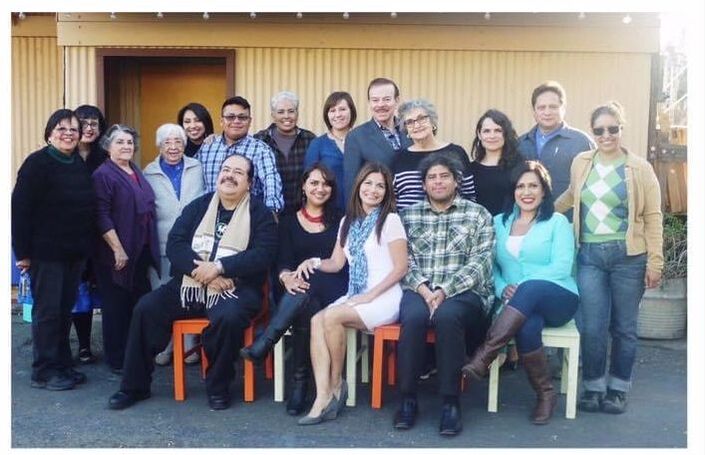

NANCY AIDÉ GONZÁLEZ THE POET: A PERSONAL NARRATIVE I was born on a hot day on July 3rd at 12:24 PM in the Imperial Valley to my parents, Amelia and Jose Luis González. I am told I came out of my mother's womb crying for life with a full head of black hair that stuck straight up. I was named Nancy because it means “Grace of God.” My mom felt that I was a gift from God because she almost lost me several times during her pregnancy. She was fragile when she was pregnant and skinny. To her, it was a miracle that I was born because she had endured a painful pregnancy. My middle name was chosen to be Aidé because my mom loved a novela that had an actress named Aidé in it who was intelligent and beautiful. Aidé is a variant form of the name Heidi which means “of a noble kind.” When I was born, both sides of my family were at the hospital. I was the first grandchild on both sides of the family. I was greeted with an abundance of love. My story is interwoven with the story of my mother and father. My mother, Amelia, was born in El Paso, Texas, and was raised in Mexico by her Tía Cuca. Her father and mother had separated when she was a baby. Neither her father nor mother could raise her, so she was sent to live with her Tía Cuca in a peach-colored adobe house in Delicias, Chihuahua. Tía Cuca took in my mother, her twin sister, Tita, and youngest sister, Armida. She and her sisters worked to earn their keep at their Tía Cuca's who had them clean, cook, and feed the chickens and pigs. There she went to school and attended a very strict Christian church. My mom came to the United States when she was 16 to live with her aunt. She worked in the fields of the Central Valley, picking fruits and vegetables. Then she moved to San Bernardino to live with her Tía Cholita. My mother always felt like an outsider. She encountered racism in high school. She was told to “go back to Mexico” and called a “beaner” by her classmates. My mom learned English in high school. My father, Jose Luis, was born in El Paso, Texas, and his family moved to San Bernardino, California, when he was a child. He did not know Spanish well. His father worked picking up garbage for the city as a sanitation worker, and his mother was a housewife. My father had four siblings. They were devout Catholics who attended church on Sundays. My father grew up playing baseball, chess, and wrestling. In high school, he was on the wrestling team. My father played saxophone in the school band. My mother and father met at San Bernardino High School. My mother was enamored with him. He was popular and considered handsome by the girls. They went on dates, but my mom's aunt was strict and would only let my mom stay out until seven in the evening. My mother was very religious and conservative while my father went to parties and dated other girls. After they graduated from high school, they continued to date and fell in love. Eventually, they got married in a church in 1976. There are photos of them at the wedding in an album. My mom wore a white dress made of lace and looked radiant. My father had a light blue bow tie and cummerbund. They are smiling in their wedding pictures while they cut the three-tier cake and have their first dance. In the wedding photos, they are full of hope and joy. They were young when they married. My mother had me a year later when she was 23 years old. She decided to go to junior college. My father worked at a carpet business for a while, laying down carpet in homes. My brother, Michael, was conceived two years later. Then my father started to work for the Santa Fe railroad. He began traveling to lay down tracks and fix the railroad tracks in different cities. My brother was born when my father began working for Santa Fe railroad. Then one day, my father injured his back, laying down the tracks for the railroad. The doctor gave my father prescription drugs for his back pains. The prescription drugs were not enough. My father turned to illegal drugs and alcohol to escape the pain. He began hanging out with people who did illicit drugs and became an addict. I was three years old at the time. Once someone becomes addicted to drugs, their lives change, and priorities shift. The addiction takes over, the person's personality changes, this is something I learned as a child. My father's addiction affected our family. My mother did not allow drugs in our house. My father was angry, jobless, and in pain. He would leave my mother, brother, and me for weeks, then months. Each time he returned, my mother and father would argue. My father would beat my mother. I would hide in the closet among the softness of clothing in the darkness. My brother would be crying in his crib. After my father beat my mother, he would leave the house as quickly as he arrived. The door would slam and shake the house on F Street. The engine of his yellow Duster would rev then speed away. I would come out of the closet to find my mother on the floor. She usually had a black eye and was bleeding from her nose. I would lay on the floor and hug her. We would cry together. Then my mother would eventually get up off the floor. She would clean her face and put ice on her eye. We would sing Christian hymns until we were tired. A few days later, my father would come home and beg my mother for forgiveness on his knees. He would promise he would change and cry. My mother would forgive him. For a week, there would be peace. We would go to church together. My mom and dad would hold hands while watching TV. Then my father would leave. The last time he left, I was five years old. He called my mom from a crackling payphone in September 1982. He told my mom that he was going to make a lot of money on a business deal. The money was going to change our lives, and everything was going to improve. A few weeks passed, and my father was found with fifteen bullet holes in his chest. Joggers in the Arrowhead mountains discovered his body in the bushes. The autopsy report indicated the last thing he had eaten was blood oranges. The police did not investigate or look for who killed my father. Due to the condition of my father's body, at his funeral, the casket was closed. I remember people at the funeral whispering while looking at me, “Do you think she knows she won't see her father again?” I remember staring at the black and white tile of the funeral home while a woman from our church sang “Amazing Grace.” I understood that my father was no longer alive, and I would never see him again. A recurring nightmare during my childhood was that my mother and brother were in a car accident. In my dream, they were in the yellow Datsun driving by in front of the house on F Street in San Bernardino. Then a semi-truck would come out of nowhere and crash into the Datsun. I would witness the crash in slow motion. In the dream, I would want to move from the porch to run towards them, but I could not move. I would be frozen, and when I screamed, nothing would come out of my mouth. I would wake up in a sweat, unable to move. I learned early on that words had power. I learned that the words my father yelled at my mother hurt her. I learned that the words of the lullabies my mother sang to me soothed me. I learned that lyrics in music I listened to by the record player could move me to dance. I learned in church that the words of the Bible were important. Words could build up or tear down. They could hurt and create invisible scars. My mother taught me my letters and numbers when I was four years old. She was in junior college and then attended San Bernardino State University. She wanted to be an elementary school teacher. She worked as a teacher's aide when I was in kindergarten while going to University. My mother would read books to me. I loved when she read me Goodnight Moon, Curious George, Little Red Riding Hood, and Five Little Monkeys Jumping on the Bed. I would ask her to read the books over and over. When she took me to the library, I was overjoyed to pick new stories that ignited my imagination. I struggled with reading in first grade. It wasn't until mid-first grade that I was taken to the optometrist. I had acute astigmatism and chose glasses with dark purple frames. I was delighted to have my glasses because, for the first time, everything was clear. Then to my dismay, I wore the glasses to school, and children made fun of me. They called me “four eyes,” and a boy told me, “You look ugly.” I sobbed in the bathroom all recess, and when I got back to class, I shoved my glasses to the back of my desk. I didn't wear my glasses at school. However, I needed my glasses to see, so I did not know what was going on in class. I couldn't see the letters on the board; everything was a blur. I disliked school, and I would daydream. I was seated in my chair in the classroom, but my mind was somewhere else. I would imagine being “Wonder Woman” and sliding down rainbows. It wasn't until third grade that I began to wear my glasses at school. I learned to read in third grade because I could actually see the words on the page without squinting. I had a reading anthology that my teacher sent home with me. I would practice reading every night with my mom or stepdad. One of my favorite teachers was Mrs. Whitfield. I had her for both fifth and sixth grade in El Cajon, California. She had us read Johnny Tremain, which is an historical fiction novel written by Ester Forbes set before the American Revolution. I remember that Johnny hurts his hand as a silversmith and could no longer use it. I felt empathy for his character, who had one hand and had a love interest named Cilla. It was the first young adult novel that I read that moved me. After reading Johnny Tremain, I became an avid reader. I would go home and read until it was time for me to go to sleep. Mrs. Whitfield also had my class memorize a poem a week. I remember we had to recite poetry to her and get graded. I memorized “Eldorado” by Edgar Allen Poe and “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost. She also let us pick poetry to read in front of the class. I was timid and I remember I chose to read “Let America Be America Again” by Langston Hughes in front of my class. I was only 12, and I did not fully understand all the concepts the poem addressed. I remember the line, “Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed-…” I remember shaking while reading the poem, each word was loudly spoken with conviction. The class clapped after I read the poem, and Mrs. Whitfield said, “Nancy is a poet!” Mrs. Whitfield believed in me and pushed me out of my comfort zone. She expected a lot from me as a student, and I excelled in her class. She made me feel seen. She awarded me a student of the year award in six grade. I don't think there is an exact moment that one becomes a writer. I just know that I liked to write. I remember writing a short story about a grandfather and granddaughter in seventh grade. My English teacher read the story to the class and said I was talented. After class, he took me outside and told me I should consider going to college. I told him I planned on going to college when I grew up. My mom and stepdad had ingrained the idea into my mind that I was going to college when I was six years old. My mom would take my brother and me to daycare to attend afternoon classes at San Bernardino State University. After class, my mom would let my brother and me run in the grass. My mom met my stepdad, John, in a Mexican history class. They were friends at first then they began dating after my father passed away. I did not trust John when I met him. I would not talk to him and did not make eye contact with him. Then he slowly became an integral part of my life. He would take my mom, brother, and me to pizza. He would babysit my brother and me. My brother and I did things with him that we were not allowed to do when my mom was around, like jump on the bed and dance. He took us to have chili dogs for breakfast. He told us dad jokes, and he still does. My stepdad accepted my brother and me as his own. John and my mom got married when I was nine years old. My brother and I were in the wedding. I was the flower girl, and my brother was the ring bearer. My mom and stepdad have been married for thirty-four years. It is from them that I know how love can change lives. In high school, I would write in a journal about my thoughts and feelings daily. I took Honors American Literature, where we read The Scarlett Letter and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. I took Honors World Literature, where we read Things fall Apart by Chinua Achebe and other African literature. I never saw myself in the books and stories that I read until my sophomore year at California State University, Sacramento. I took a Chicana Literature course taught by Professor Graciela B. Ramirez who assigned books by Chicana authors that impacted my life. I read Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza [1987], a semi-autobiographical work by Gloria E. Anzaldúa. I read Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma by Ana Castillo. I read This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, the feminist anthology edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa. I read The Moths and other Short Stories by Helena Maria Viramontes. I devoured these books because I saw myself in the essays and literature. I found myself and my culture described within the pages on these books, and it was empowering. It was the first time in my life that I thought I could be a writer. I was published in Calaveras Station, the literary journal at Sacramento State. I was overjoyed when I saw my poem in print. Years went by, and I became an elementary school teacher. I would write poems in journals and napkins, but I never shared my work. It was not until 2011 when I decided I was going to take my writing seriously. I became very depressed because I wanted a child. I had been trying to conceive a child for a year. I have polycystic ovary syndrome, and I was put on metformin by my doctor. It made me ill, but I stayed on the metformin. Then one day, my mother said, “I hate seeing you sad. Perhaps you should accept that you might not ever conceive a child.” I contemplated this idea for a few weeks. Then I decided that if I could not conceive a child that I would give birth to thoughts and words in the form of poetry. Poetry brought me back to life. I began writing poems and joined Escritores Del Nuevo Sol. At my first meeting, I read a poem about my female ancestors called “The Ones that Live On.” It was my soul that urged me to write the poem. Francisco X. Alarcón was a member of Escritores Del Nuevo Sol; he encouraged me to keep writing. Francisco X. Alarcón had a significant impact on me as a poet. He asked me if he could publish my poem on Poets Responding to SB1070 on Facebook. There, on Poets Responding to SB1070, I met other writers who were activists from across the nation. Joining a community of poets helped me gain confidence and discover my voice. I also joined the Sacramento Poetry Center and began hosting a poetry reading series called Mosaic of Voices for three years. I met brilliant poets while hosting the reading series. The readings were on Sunday afternoons; they became like church. Each poetry reading was spiritually and intellectually moving. I began submitting my work, and my poems were published in several literary journals and anthologies. My poetry friends became like a second family. When I begin writing, I don't know where the poem is going or what will spill out onto the page. Sometimes I write poetry, then take a few lines and write another poem. Other times, a whole poem will come to me in the middle of the night, and I will get up and write it. Poetry that comes to me in the middle of the night rarely needs to be edited. Some poems I revise and re-edit until I feel they are done. I know when a poem is done when I feel it in my heart that there are no words I want to change or images I want to insert. Writing allows me to explore my emotions and communicate ideas about the world around me. Poetry has helped me heal and has forced me to deal with pain. It has helped me understand my life experiences. It has helped me forgive others and myself. I have written poems about my father and my infertility. It has helped me transform into a more introspective individual. Part of being a writer is observing and experiencing each moment. I notice the smallest things, dust in the air, the smell of earth, and sunshine through leaves. Poetry allows me to take my pain and make it into something heartbreakingly raw and beautiful. My soul moves me to put pen to paper and give birth. THE POETRY OF NANCY AIDÉ GONZÁLEZ: “…something heartbreakingly raw and beautiful” La Virgen de Las Calles for Ester Hernandez She stands on the busy street corner selling delicate red and white roses hugged by baby's breath and luminous cellophane resting in a once discarded plastic bucket. She understands the innate beauty of roses, their fragility their fragrant hope as they grow slowly from bud to emerge embracing change, as they flush into full bloom. She knows of piercing thorns and truth of crossing barbed wire borders. She understands the prickling sting, the aculeus of being an outsider. She wears a large sweatshirt with USA emblazoned in block print across her chest but she misses Mexico and the small town she was raised in. A red and green rebozo hangs down upon her head shielding her from the fulgent sun, a gift from her mother, a reminder of home. People stride past her lost in their own thoughts hustling to work, on pressing errands, wandering down the tangle of the Los Angeles landscape. She is La Virgen de las Calles, waiting with a heavy heart, full of yearning, dreaming of new horizons, a fountain of humble tenderness and abounding love. La Virgen de las Calles comprehends the nature of roses, their vulnerability their need for nettle. Rose Ranfla Riding in the ’63 Impala cruis’n el corazón del barrio passing by carnalitos y carnalitas running through sprinklers abuelas y abuelos on the porch talk’n about the old days cholos playing handball at the high school women in the beauty shop getting their hair did rollin’ past taquerías panaderías heladerías Bumping I’m Your Puppet La La Means I love You Thin Line Between Love and Hate Sabor A Mí through the streets of Califaztlan Chrome spoke wheels spin low and slow variations of pink paint layers glisten hard top covered in a garden of hand painted gypsy roses lean back upon velvet pink interior flip the switch hit the hydraulics dip and raise dip and raise hop hop hop off the ground in the intersection the journey has just begun let’s chase the immensity of the moment in estilo. Serenade I become earth’s remembrance of everything creviced skin of red rock endless pregnant season toothless silence I want to understand this world, your scars stay cradled by tree arms delve in splinters my womb is filled with clay barren it throbs I want to say many things but my words are trapped in caverns where bats hide from redundancies no one told me of the gritty essence of the residue that settles Black star dying innumerable deaths in this life we have come here to the waters we are he and she or man and woman scent of copper and jasmine we sip smoldering gravity separated space fills a serenade in golden afternoon unborn twins sob otherworldly whimpers timeless they can be heard by the bees and ants they enter this wasteland we inhabit nameless they will remain, my infants Adrift we are. Come to me. I am alone. wild horses turnover the headstones take my ovaries spine skull take the truth I search for in crushed leaves, in the fading contrails of fading light. Zapata y Frida By chance they meet at a bar she drinks tequila shots she wants to be life itself he caresses his gun he longs for uprising. he strokes his mustache, his wet lips glistening she touches her brow, her eyes aflame they speak of monkeys and flowers, of war and borders in the corner they become the world itself, spinning off axis they laugh loudly and don’t notice people staring “Take me away,” she says. II She places her hands on his face studies his indigenous features examines his eyes “I know you” she says. “I have known you all my life. You will cause my slow death.” III She unbraids her hair her pink ribbons fall to the tierra he take off her embroidered dress he places his hands upon her small breasts they devour each other’s skin thrusting and precise piercing moaning until night melts into brightness there are no promises made upon the wet grass after she places her head upon his chest and hears the drum of his heart “You will remember me.” she says. IV They ride horses through Morelos near sugar cane fields “It is better to die on your feet than live on your knees,” he says. “Death knocks at my door,” she says. “I have no mercy,” he says. “Please have mercy on me,” she says. VII The next time they make love she unhinges him touches the wilderness with abandon hunger drives them deeper into the topography of vermillion desire VIII An eagle sits on a cactus and watches them dance to corridos she pulls him close with her rebozo “We are home,” she says. IX That night she has a dream she is in the forest alone she is a deer and arrows puncture her flesh she awakes sobbing and gasping paint splattered on her face She reaches for him. “No llores,” he says. “I want to be your soldadera,” she says. X He vanishes in the middle of the night he leaves her a rifle with a rose in the barrel she takes her brush and paints. Railways Smell of dirt and sweat Mingled with whiskey and cigarettes the train resounds, he is home. All day he mends railroads comes home & takes of his dusty boots, the sour aroma of twilight. I watch his face think of the softness of the figs growing in the backyard, play with dolls. He calls me outside talks to me as he smokes a joint about constellations and the dangers of night, I tell him of the butterfly I caught and set free. The red porch paint peels, nearby the cactus grows entangled this is our small space his jagged hand caresses my face, above a shooting star scars the sky. Then he and my mother fight A blur of fists, blood his departure marked with dissipating smoke. I don’t want to know the details of where he went or how he felt as all those bullets punctured his flesh. All I hear is his distant voice on the cracking phone line saying, “I will be home soon.” On the way to the funeral we stop as the train roars car after car after car speed by weight & rhythm of wheel on steel, he has gone home. Foreigner I am a foreigner in my own country there is torment in the disconnection, I examine the geometries of mountains and plateaus pass by clamorous rivers, the land remains the same. The land remains the same in the mirror, reflection my face is my own my wide brown eyes my carefully drawn red lips, the world has changed. The world has changed, I send a letter to a good friend Wait for an answer that might never arrive, the mailbox is empty I must fill my own emptiness. I must fill my own emptiness the dirty laundry piles up, politicians recite alternative lies on television lying has somehow become the norm, I march with millions in protest against injustice raise my voice for the voiceless, raids round up “unauthorized” immigrants to be sent to Mexico, there is an unraveling of fear and hate. There is an unraveling of fear and hate my soul knows the unsayable, I drive to work and back home throw things on the ground to see how they fall, pick up wilted flowers try to revive them, find a dead seagull on the path blood encrusted with dirt broken wing hanging, I search for the bare skinned essence of light within darkness. I search for the bare skinned essence of light within darkness, at the park a small girl holds a red balloon she becomes distracted by laughter lets go of the string watches the balloon float to meet the sun, I want to peel the sun lay my fingers on permanence. I want to peel the sun lay my fingers on permanence, rays illuminate a thick black arrow tattooed on the cashier’s forearm, I want to follow the arrow to where it might take me, so I may arrive at the unseen, become connected. I am a foreigner in my own country the land remains the same yet my world has changed, memory filters through lace wings those I thought I knew, have become strangers. Expedition of the Heart for Christina Fernandez A woman’s voice whispers in español there is no silence during daylight hours only memory arranged and scattered days that become years map charted life air thick with absence, un canto. 1910, Leaving Morelia, Michoacán Through Michoacán the fishermen throw nets into clear waters fish sink heart sick light is submerged revolution leaves dust thick insurgent shapes arc She clasps her hands gazes out in the womb a child stirs door-heart creaks in the empty house resolve ripens becomes honeyed she has died and has been resurrected she must leave the river that sings now the monarch beckons. 1919, Portland, Colorado Stains have been scrubbed in laundry detergent bleached in stark bubbles that shine like prismatic marbles creating rhythm on washboard ridges soft hands massage grime, bitterness Wooden pins fasten three shirts and a bed sheet alabaster they flap in the breeze She knows she must travel lightly leave segments to soak to lift to float feathered and bask in the impermanent sunlight. 1927, Going Back to Morelia What is known, will be known what I take in this black chest is not mine, it is ours. These tracks will take me back to the smell of copal and agave nectar where I will kick the scorpion and hold the snake I will invoke la Virgen. I clasp these words written on crumpled paper words that have carried me through vacant terrain I hold these needles which I will use to thread together shreds mend each emotion filament by filament. I am not who I was you will know me anew I will rename each radiant blade of grass each distant storm after you. 1930, Transporting Produce, Outskirts of Phoenix. Arizona Be careful not to bruise the apples that is not to spoil the flesh I was told to twist the stem gently leave the tree as it is fruit is placed into wooden crates, carried to the truck We were told there would be water and a bathroom there wasn’t we were told we wouldn’t be sprayed with pesticides, we were we were told many lies. We watch majestic seasons clinched in foliage shift follow the crops in old cars where they lead we are strangers yet friends we are hombres y mujeres always leaving behind something someone each other always searching orchards and rows for distant secrets, trying not to bruise. 1945, Aliso Village, Boyle Heights, California I trust one and perhaps I trust none I wear an apron sweep and mop the houses of others, then my own I clean mirrors so I can see what is and what is not wipe reflections with rags as solitude encloses After dusting, motes remain and gather these granules the soul accumulates. How far I have come, each sepia detail crisscrossing small daily miracles. 1950, San Diego Faith has brought me to where I am These things I touch with my two hands: a hot stove, pots, pans, a cup of tea, my children I belong to myself, to others. This space is mine this spot where the floor is illuminated and love collapses I need to tell you, you are enough you will leave pieces of yourself scattered through the world you will be drawn back by generations of madres, padres, hermanas, y hermanos you will envision your ancestors existed far removed from desolation that they were not lost You will scrape together details of their lives become the author of your history tell their stories with your words Our narratives will continue we will find our way home. © Poetry: Nancy Aidé González Nancy Aidé González is a Chicana poet, educator, and activist. Her work has appeared in Huizache: The Magazine of Latino Literature, La Tolteca, Mujeres De Maiz Zine, DoveTales, Seeds of Resistance Flor y Canto: Tortilla Warrior, Hinchas de Poesía, La Bloga, Fifth Wednesday Journal and several other literary journals. Her work is featured in the Poetry of Resistance: Voices for Social Justice, Sacramento Voices: Foam at the Mouth Anthology, and Lowriting: Shots, Rides, and Stories from the Chicano Soul.

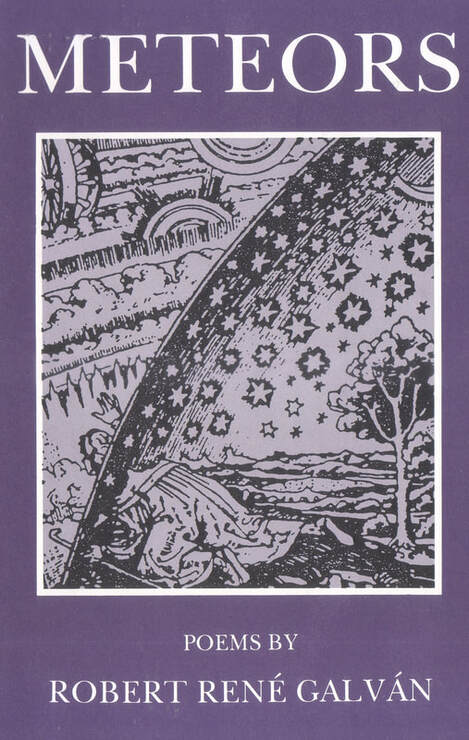

Edited by poet and writer, and member of Círculo de Poetas y Escritores, Lucha Corpi, for Somos en escrito Magazine. In search of parchment, indelibilityExcerpt from Meteors, a collection of poetryby Robert René GalvánGRAFFITI Take this glowing script As a burnt offering Of chrism from my brow. Midnight oil consumed By the greedy darkness, When my wick grows dim And words become a relief Of amoebic spectres On the wall. We are the same, A whimsy of dancing hands, Indigo faces in search Of parchment, Indelibility: The stealth of youths And the stench of sprayed Rebellion in the trainyard, A lover's vow scratched in oak, Or in wet cement, The bathroom bard, Granite elegies, Scars of melody on vinyl, Frozen images on celluloid, And shadows made fast on wafers Of dead tree. My own strokes are engulfed By solitude, Like footprints on the moon. They are faint adumbrations, A sack of spores Waiting to be strewn From the folds Of paper birds. An earlier version of "GRAFFITI" appeared in Sands. LA PARTERA My grandmother's raisined hands Guide a new life through the meniscus of sleep and into the blinding day. This has been her ritual for fifty years: The phone rings -- The metallic music of her black bag Answers back as she flies to a neighbor's house. She prepares her fingers in boiled water As if to coax sweetness out of those dried figs And waits for the mother to blossom. But this one's a breach, Poised as if trying to break his fall, feet first. Calmly, she finds the baby's mouth With her finger; He bares down to suckle And she turns him toward the light. Age and aches have not dissuaded her For her room is filled With reminders of her faith: A statue of La Virgen, Bottles of holy water Among brittle blades of palm, And countless gift rosaries That grace the bedposts; She caresses each pearl And prays for stronger hands. MEMORIAL for Woody McGriff, dancer 1957-94 The blood-dimmed tide is loosed.... -- W.B. Yeats An obsidian wing glanced my shoulder Amid the languid trance of cicadas Seething in the midday heat. It fluttered like an errant leaf And summoned the splendor of your dance, Flight frozen like a Rodin bronze, Fixed by a flash of incorruptible light. But the heavy tide drew you under, The once supple leaps reduced To a lumber toward a distant sea.  Robert René Galván, born in San Antonio, resides in New York City where he works as a professional musician and poet. His last collection of poems is entitled, Meteors, published by Lux Nova Press. His poetry was recently featured in Adelaide Literary Magazine, Azahares Literary Magazine, Gyroscope, Hawaii Review, Newtown Review, Panoply, Stillwater Review, West Texas Literary Review, and the Winter 2018 issue of UU World. He is a Shortlist Winner Nominee in the 2018 Adelaide Literary Award for Best Poem. Recently, his poems are featured in Puro ChicanX Writers of the 21st Century. He was educated at Texas State University, SUNY Stony Brook and the University of Texas. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed