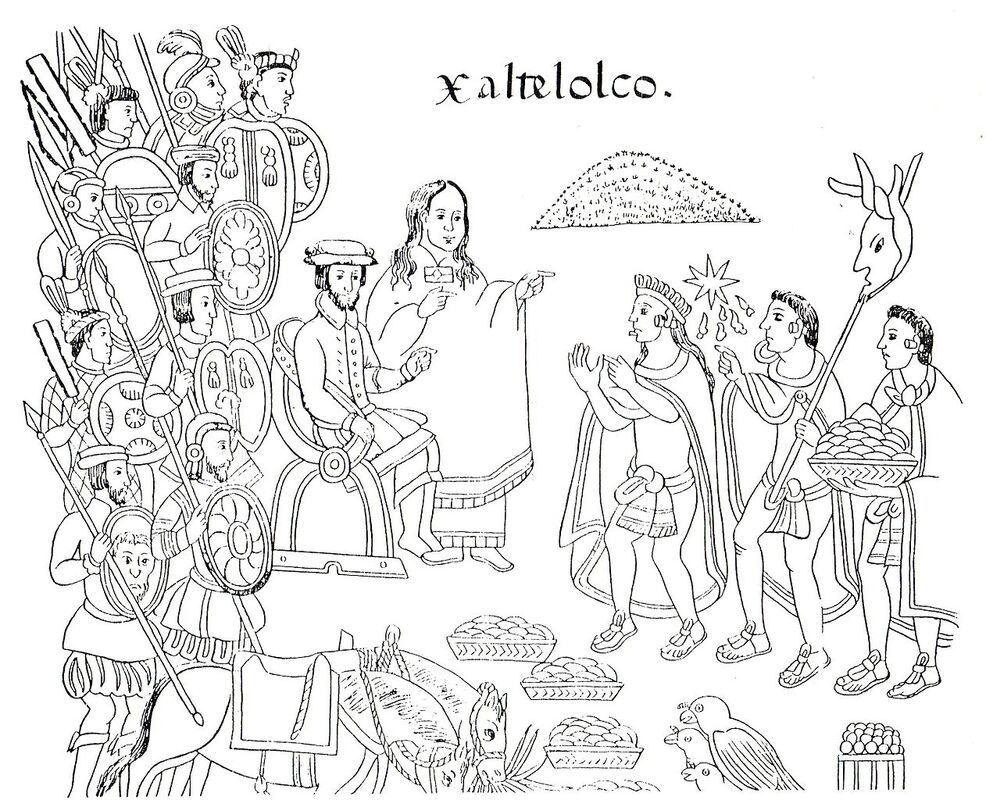

Como con las manosby Elizabeth Jiménez Montelongo I want to hold my food Feel it with my fingers The texture on my skin Before I taste it I want to feel The oily tortilla of my taco al pastor I want to feel that rough tostada de ceviche That loses toppings As I crunch it I want a warm tamal in my hand Salsa y queso y crema Dripping off the sides I want to eat that birria right: Con tortillas, en tacos, quesabirria Consomé dripping off my chin I want that chile verde in the gorditas And on the sopes to end up All over my fingers So I can lick it off I want to mop the mole off my plate With a warm tortilla My daughter wants to eat salad or eggs With her fingers? Enjoy Roll up a pancake and eat it Like a taco? Go for it Hold those little trees of broccoli Pick up those peas and frijoles one by one Like they’re gems Touch that food, shape it, arrange it Some call it “playing with food” I call it “art” and my mom let me do it Orange Mexican rice teokalli Little flat-topped pyramids de arroz Were my recurring sculptures Table manners are for tables Not for people who know How to experience their food Long before it gets in their mouth Some would judge my way of eating But so what if my elbows Are on the table At least I’m not putting My codo on the minimum wage So what if I slurp my caldo de pollo At least I’m not slurping All the profit off someone else’s labor So what if I lick my fingers, smack my lips At least I’m not licking or kissing Anybody’s anything para quedar bien So what if I play with my food At least I don’t play With other people’s lives So what if I burp It’s better than talking hot air Making promises I won’t keep There are some things I’ll never know Like why I’ve never Eaten enchiladas con las manos – yet Or why there’s a limit to how high I can pile the pozole on my spoon But what I do know is that When my napkin stays on the table You can bet I’m leaning over my food, breathing it, Holding it, savoring it, The way food was meant to be handled I leave nothing on my plate Snatch up those bits of carnitas Every last crumb of milanesa Belongs in my mouth And I’ll enjoy the leftovers con salsa Mañana That’s how to handle comida ¡Con las manos! Crunch those buñuelos Let the crumbs of criticism fall On a tapete of repurposed judgment Reduced hierarchy Recycled capitalism  Elizabeth Jiménez Montelongo is a visual artist, poet, and facilitator. Elizabeth's work is informed by her Indigenous ancestry, Mesoamerican philosophy, Mexika & Mixtec art, Mexican culture, Chicano history, and her experiences as a woman. Her paintings and sculptures have been exhibited across the United States and her poetry is published widely, including in print and online journals, and in anthologies such as: Nos pasamos de la raya/We Crossed the Line (2017), Azahares (2020), and Harvard’s PALABRITAS (2020). She was 2021 Creative Ambassador of the San José Office of Cultural Affairs. She is a Board Member of Poetry Center San José and Editor of La Raíz Magazine. www.ejmontelongo.com

1 Comment

Poetry on going beyond stars |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed