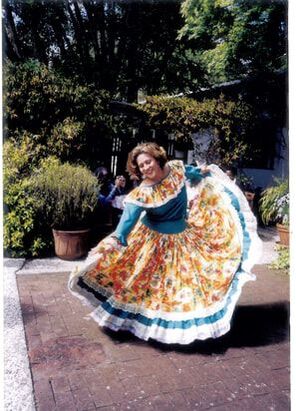

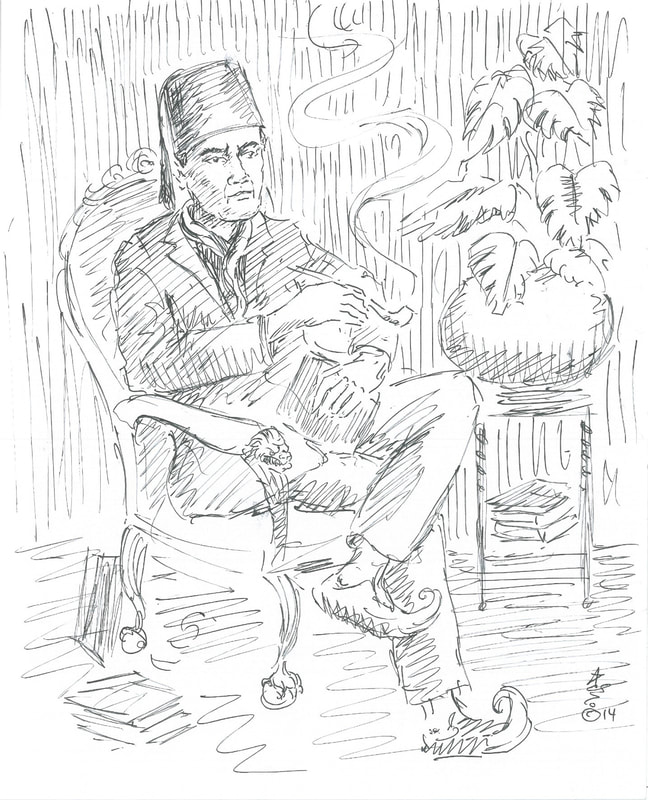

“Por escrito” Lucha Corpi (LC) entrevista a Graciela Brauer Ramírez (GBR), Catedrática jubilada de la Universidad Estatal de California en Sacramento. Poeta y narradora chicana, y trabajadora cultural incansable. Miembro de “Escritores del Nuevo Sol” en el Valle de Sacramento y de “Círculo de poetas & Writers” en la Bahía de San Francisco, con sede en Oakland. AZTLÁN – El lugar de las garzas LC: Querida Graciela, cómo se ve claramente, en la portada de tu libro están estampadas las garzas, aves que normalmente habitan a orillas de los ríos en California y en México: Algunos de los ríos más caudalosos se encuentran en el sur de México y precisamente en el estado de Veracruz y cerca de la Ciudad de México de donde eres originaria. Me fascinó ver que tu obra comienza con una descripción del Río Americano (the American River) que atraviesa de lado a lado la Cd. de Sacramento, capital del estado de California. Según la leyenda indígena mexicana, AZTLÁN era el lugar de origen de las varias tribus pre-colombinas, las que poblaban el continente de América, desde Alaska y Canadá hasta Tierra del Fuego en Sudamérica. A primera vista se podría también decir que EDUCACIÓN: Una Épica Chicana de la catedrática, poeta y narradora, Graciela Brauer Ramírez, es un libro de texto histórico. Ofrece una visión y cronología histórico-política de acontecimientos que se suscitaron en la Cd. de Sacramento, capital del estado de California, durante las décadas de 1960 a 1980. Al mismo tiempo, ofrece una vista panorámica del movimiento socio-político y pro-derechos civiles del pueblo México-americano en EE.UU., es decir de la población que se autodefine políticamente como chicanos. De una manera más general, bosqueja también el impacto de los logros de esta población, desde entonces hasta la fecha. Desde el punto de vista literario sigue las reglas de una epopeya clásica, es decir como lo fueran la Odisea o Ilíada en la antigüedad. Es un relato en verso y trata de las hazañas de héroes en tiempos de guerra y en defensa de su pueblo, su historia y cultura. Más aún, es la infra-historia de una familia californiana, con fuertes lazos culturales, literarios e históricos, con México y el sudoeste de Estados Unidos. Gracias. Graciela. Lucha Corpi Entrevista y plática: Lucha Corpi (LC) y Graciela Brauer Ramírez (GBR) en conversación. Influencias: En familia o comunitarias: LC: Tu obra culturalmente es parte de una tradición oral, pero lo es también de la literaria. Es en verdad, Una Épica Chicana, y una obra monumental. ¡Enhorabuena, Graciela! Ahora, cuéntanos un poco sobre tu niñez y adolescencia en familia. Sabemos que tu padre fue de gran influencia en ti, quien estimuló tu sed intelectual por el conocimiento y la lectura. Aprendiste a leer a los cuatro años. Entiendo que tu convivencia con otros parientes, en ambos lados, también fue muy importante. En familia, aparte de tu papá y mamá, ¿Quiénes más fueron de gran influencia en ti durante tu niñez? GBR: Como digo en mi libro, Una épica chicana, por las noches, en familia, nos juntábamos en el patio y cada uno decía poesías o contaba historias. Por ejemplo, a mi tío Homero le gustaban las historias del mar y de barcos. Después fue marinero. Mi tío Sergio siempre nos contaba la misma historia sólo le cambiaba los nombres de los personajes. A mí me subían en una silla y recitaba: “Mamá, soy Paquito, no haré travesuras…” Y también una que dice: “Guadalupe la Chinaca va en busca de Pantaleón su marido…” Dado que a los 2 o 3 años yo no podía todavía hablar bien, recitaba este verso a mi manera: “aupe anaca busca a neon maido…” Mi tía Elena, aun cuando ya estaba yo grande, se burlaba de mí imitándome, pues a esa edad temprana no podía yo hablar claro, pero, según yo, ya recitaba. También mi tía me decía que cuando terminaba yo les pedía aplausos al “púbico” (el público). LC: Me haces reír. Muy divertido. Ya entrando a la secundaria, ¿seguiste recitando poemas en público? GBR: Claro que sí. Ya de estudiante, en la secundaria, recitaba en concursos y en uno de ellos gané el primer premio al recitar de memoria el poema “Los Motivos del Lobo” de Rubén Darío el gran poeta de Nicaragua. Hasta la fecha, ya en mi vejez, aún recuerdo todo este poema tan largo. LC: Entonces, en cuanto a los lugares que fueron importantes en tu desarrollo durante tus años tempranos, sabemos que naciste y viviste en la Ciudad de México y que sufriste los calores y el bochorno del trópico en el puerto de Veracruz. En el prólogo de Educación: Una Épica Chicana, JoAnn Anglin, gran poeta y narradora, a quien también tengo el gusto y la honra de conocer, nos da algunos datos personales tuyos, pero bastante esquemáticos. LC: Si te es posible, cuéntanos un poco de ti, de tu vida personal antes de unirte al cuerpo docente de la Universidad Estatal de California (California State University at Sacramento-CSUS). GBR: Las gentes que tuvieron más influencia en mi infancia fueron mi papá y mi tía abuela Juanita. El me introdujo a la lectura, al grado de que cuando fui al kínder ya había leído varios libros de cuentos que él siempre me compraba. Mi tía abuela Juanita tenía una tienda de abarrotes a media cuadra de nuestro apartamento. Ella tenía su recámara arriba de la tienda. A veces ella me cuidaba o cuando iba a la tienda inmediatamente subía a su recámara pues ahí tenía muchos libros. Ahí leí: Corazón Diario de un Niño, Las Mil y Una Noches y muchas otras obras que aún viven en mi mente y que me han ayudado a sobrevivir. Un día mi tía me sorprendió mucho cuando me regaló estos dos libros y algunos más. También mi papá. Él era militar, y por algunas horas, también valuador en la mayor casa de empeño controlada por el gobierno. A veces tenían subastas y la mercancía que quedaba la repartían entre los trabajadores. Esta era generalmente de libros, los cuales él traía al apartamento. Entre esos libros leí, con ayuda de adultos, La Vuelta al Mundo en Ochenta Días, El Jorobado de Nuestra Señora de París y muchos más. Fui muy afortunada. LC: Nos has contado que debido al trabajo de tu papá, quién era militar, viviste en diferentes lugares. ¿Cómo afectó el pasar tu infancia y adolescencia en comunidades tan diferentes una de la otra? GBR: Primero, era una bebé y mientras que las mismas personas me cuidaran, no había problema. Después, cuando contaba con cuatro años, mi papá me ponía en el tren los viernes por la noche y mi abuelito me recogía en el puerto de Veracruz en la mañana del sábado. El regreso era viaje opuesto, por supuesto, de domingo en la noche a lunes por la mañana. También pasaba todas las vacaciones en la costa del Golfo de México, que era la costa veracruzana. Vivir en el puerto de Veracruz fue para mí una experiencia muy afortunada pues mi abuelito era una persona muy educada al haber estudiado en el seminario; había leído mucho. Con él aprendí bastante. También en Veracruz vivían mis tíos quienes eran muy adeptos a las poesías. Mi tío Carlos, por ejemplo, sabía muchas de ellas de memoria. En las noches nos recitaba versos de sus autores favoritos como Díaz Mirón, poeta veracruzano. Mi tía Estela recitaba en las escuelas. Aún recuerdo una de sus poesías favoritas que dice: “…espera la caída de las hojas.” Mi abuelito y su hijo mayor trabajaban en el ferrocarril me conocían y me querían bastante. A menudo, ellos me llevaban de viaje. Durante mis viajes la tripulación del ferrocarril me cuidaba. LC: Cuéntanos también de tu familia materna y de tu educación formal y adolescencia GBR: Cursé la primaria en El Colegio de San Ignacio de Loyola comúnmente conocido como Colegio de las Vizcaínas, una escuela católica en la Ciudad de México. Mis padres se divorciaron cuando yo tenía menos de un año. Mi papá tomó la responsabilidad de criarme. Él era militar así es que yo crecí regimentada, cosa que siempre le he agradecido pues aprendí disciplina, algo que me ha servido toda mi vida, y que él hizo con mucho amor. A los 15 años me fui a vivir con mi mamá. Ella era una famosa cantante de música ranchera. Mi vida con ella era excitante pues me llevaba a los teatros y estaciones de radio en donde conocí artistas famosos de aquella época. Por otro lado, ella era una persona muy extrovertida y se impacientaba mucho conmigo por ser yo sumamente introvertida. Con ella viajé en sus giras por muchos estados de México y lugares en los Estados Unidos como las ciudades fronterizas de El Paso, Texas y San Diego, California, además de Los Ángeles en California, entre otras. Desgraciadamente mi mamá y yo éramos demasiado diferentes. Ella era una feminista que a los 40 años se hizo torera aficionada; yo vivía dentro de los libros. Con mis padres crecí en dos mundos completamente opuestos. Sin embargo, en ambos mundos, todas mis experiencias fueron muy buenas. LC: En esta entrevista quiero hacer resaltar no sólo tu trayectoria poética-literaria sino también tu participación en el movimiento pro-derechos civiles y humanos del pueblo chicano en Estados Unidos. Al leer tu obra, me doy cuenta que tú fuiste testigo y participante en muchos de los acontecimientos que describes en tu libro durante “el movimiento chicano”. Cuéntanos sobre esta importante época de tu vida. GBR: Mi participación en los primeros años de pertenecer al movimiento chicano, fue la siguiente: ayudaba en lo que podía como organizar eventos poéticos, así como los Simposios de Pensadores del Tercer Mundo y otros más. También ayudaba en sus funciones para recaudar fondos como ventas de pan dulce, tacos etc. Me daba de voluntaria para ayudar a organizaciones como CAMP (College Assistance Migrant Program) entre otras. También tuve en el barrio, en el Washington Neighborhood Center, un programa tutorial en el que llevaba estudiantes de la universidad a enseñar a los niños. Lo óptimo de mi participación fue cuando formulé y comencé a enseñar el curso “La Mujer Chicana” en el Departamento de Estudios Étnicos, de la Universidad Estatal de California en su campus de Sacramento-CSUS. El gran poeta y activista chicano, José Montoya, era catedrático en este mismo departamento. Después de haber recibido algunos reconocimientos por mi participación en el movimiento chicano, mi mayor orgullo llegó un día cuando José Montoya me llamó y me dijo: “Gracias, Graciela, porque nunca nos has dejado”. Este ha sido el mejor reconocimiento que he recibido en mi vida. José tenía razón. He creído siempre que es un derecho de todo ser humano tener acceso a la educación formal. Me uní al Movimiento Chicano Pro-derechos humanos y civiles. Para los chicanos, acceso a una buena educación era lo que más deseaban. Sentí como si un imán me atraía hacia ellos. También a José Montoya siempre le viviré agradecida. El organizaba programas y recitales de poesía en la universidad. Fue él quien me apoyó é invitó a leer mi obra poética en público, por primera vez en mi vida. Cómo recuerdo cuanto sufrí, y las ansias que me causó, pues tenía demasiado miedo de leer en público. Yo había leído en programas escolares pero nunca en programas en público en general. José lo notó y con sus palabras me animó mucho. Al fin, temblaba pero lo hice. La Poesía de Graciela B. Ramírez REBOZO Rebozo que humillado te escondías, mas con la revolución volviste altivo en los hombros de Frida** quien sin miedo te sacó de penumbras ensalzando los colores brillantes de tus hilos. Así volviste a colorear las fiestas adornando con gracia a las mujeres quienes ahora en cuerpos te lucían o zapateando en moños te enredaban. Rebozo que en los campos de batalla de la intemperie protegías a guerrilleras y en las noches cubriendo a los amantes creabas mundo privado en que chasquidos de besos resonaban en el aire y después el amor bajo de ti hacían porque quizá la luz del sol Ya no verían Rebozo, con tus hebras acaricias de las futuras madres sus vientres esponjados, entibiando matrices, dando calor a fetos, enlazando dos seres en comunión sagrada Cordón umbilical de madre y niño porque cuando ellas cargan, cual marsupias, a sus tiernos infantes, ellos saben que no hay peligro alguno porque tú con firmeza los sostienes. Y también con amor cubres los senos cuando el pequeño cual gatito tierno mama la tibia leche de su madre y arrullado con ritmos de latidos sueña envuelto en respiros melodiosos y despierta al sentir hondo suspiro y se ve reflejado en dulces ojos. **Nota Bene: Frida Kahlo volvió a hacer famoso el rebozo de seda mexicano. A este rebozo también se le conoce como Rebozo de seda de Santa María, el pequeño pueblo en el estado de San Luis Potosí, en donde se encuentran los telares de rebozos. Ahí mismo también se pueden ver los sembradíos de las plantas de las que se alimentan las orugas que el público en general conoce como “los gusanos de seda”. Frida también mostró el modo, arte y orgullo de portarlo el rebozo. Fue precisamente durante las décadas de los años sesenta y setenta que las mujeres chicanas, México-americanas y latinas volvieron una vez más a hacer legítimo el uso del rebozo, tanto el de algodón como el de seda. -LC Tlaloc There came a day when your gigantic statue was moved from its birth place to Chapultepec’s sacred emerald forest where hundreds of crickets sing for you the eternal welcoming song Slowly, so slowly 168 tons of stone moved through Tenochtitlan’s streets cradled in the specially-built trailer going slowly, So slowly. During the night, work crews disconnected and reconnected electrical wires needed because of your 23-foot height. Perhaps you laughed At all the attention From the multitudes After the 30-mile journey, came the huge explosion, like a Big Bang, embedding our memories back in our city recalling years of invasions, centuries of deep pain. But finally, the gift of spiritual Renaissance as you passed through the Zócalo, The Great Temple, El Templo Mayor. At that precise instant came the deluge, your fertility water, your life-giving water, your survival water, your baptismal water, your melting jade rain that poured over us running in force through our city washing us in blessings and forgiving waters through archeological sites, the burial homes of your ancestors the burial homes of our ancestors. Tláloc, the Great Tláloc: The eagle and the serpent Acknowledged you As the Lord of the Third Sun, As God of all Water. PINCELADAS Instantly becoming one With the new born moon And the eastern star All of a sudden Autumn smiles Reddish leaves Cosumnes River Witness in silence Courtship of cranes The broom Escapes from my hands Dishes Look at me with anger Only the pencil Calls me by my name Magic of Jazz Is for me Sensuality and Spirituality Interwoven Only the pencil Calls me by my name Rain, flamenco woman Dancer Stamping On the roof of my house. **CHICANOS Y LA LENGUA Esta es la historia de la gente… que nace o emigra en retroceso, a esas tierras que ancestros disfrutaron, a lugares viniendo de regreso, que ejércitos extraños conquistaron, sitio donde las grullas con su beso y su baile, colonias iniciaron. Esta es la gente que con ansia busca, un lugar en el sol, cosa muy justa. ... **EPIFANÍA CHICANA Aztlán renace, del chicano cuna su núcleo de las cuatro direcciones aurículas en Utah y Colorado ventrícula del sur en Arizona y otra en Nuevo México hechicero, Aztlán cuyas arterias cristalinas de estrellas salpicadas son Ríos Grande, Colorado y también el Sacramento. ... **LC: Estrofas de Educación: Una Epica Chicana, p. 3 y 24 GBR: Aquí estamos José Montoya y yo esperando una de las cuatro ceremonias pre-Colombinas en Sacramento (la de los niños, la de las jóvenes o Xilonen, la de los jóvenes y el Día de los Muertos). En los setenta José fue uno de los iniciadores de ellas y tuvo a su cargo el altar del norte o el de los viejitos. Yo empecé en el sagrado círculo como a principio de los ochenta y duré en la dirección del norte con José como 25 años o más que fueron inolvidables pues pasar más de 9 horas en compañía de José preparando el altar, marcar el círculo con polvo de maíz, mantener el fuego en el salmador, esperar al grupo que iba a recibir consejos y dárselos fue una de mis mejores experiencias. Con él y los Chicanos aprendí muchísimo. Generalmente leo con mi grupo “Escritores del Nuevo Sol”. Yo soy la que organizo los recitales poéticos en Sacramento. Nuestros programas son en lugares como “Sol Collective”, “Luna’s Café”, y “The Poetry Center”. Hace tiempo iba con mi grupo de escritores a leer en las ciudades de San Francisco, Stockton, Yuba City y otros lugares en California. También en ocasiones leo como parte del grupo al que también pertenezco “Círculo de Poetas & Writers” con base en Oakland, California y miembros en varias ciudades del norte de California. LC: ¿Cómo y dónde pueden los interesados conseguir el libro Educación: Una Épica Chicana?

1) De la autora: email: [email protected] 2) Sol Collective, Sacramento, California LC: No hay duda, apreciada Graciela, que has tenido una larga y fascinante carrera como catedrática y poeta. Me encanta tu actitud ante la vida: siempre optimista. Eres de gran inspiración a todos nosotros, tanto a los “Escritores del Nuevo Sol” como los miembros del “Círculo de poetas & Writers”. Mil gracias por tu participación en esta serie de entrevistas, patrocinadas por el periódico bilingüe Somos en escrito y por “Círculo de poetas & Writers” en la bahía de San Francisco. **En especial, mis más sinceras gracias a Jenny Irizary of Somos en escrito, por su paciencia y asistencia técnica en esta serie de entrevistas mes tras mes. Abrazos, Jenny. **Igualmente, gracias a Paul Aponte y Betty Sánchez de “Círculo de poetas & Writers” (SFBA) y “Escritores del Nuevo Sol”, Sacramento por su ayuda con las fotos que aquí se incluyen. © Poetry, Graciela Brauer Ramírez, de su libro: Educación: Una Épica Chicana

0 Comments

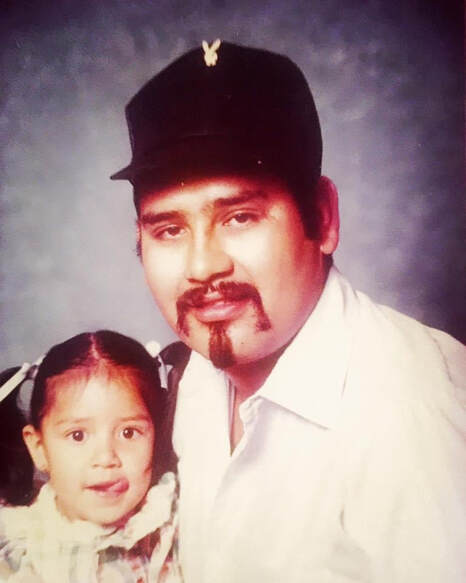

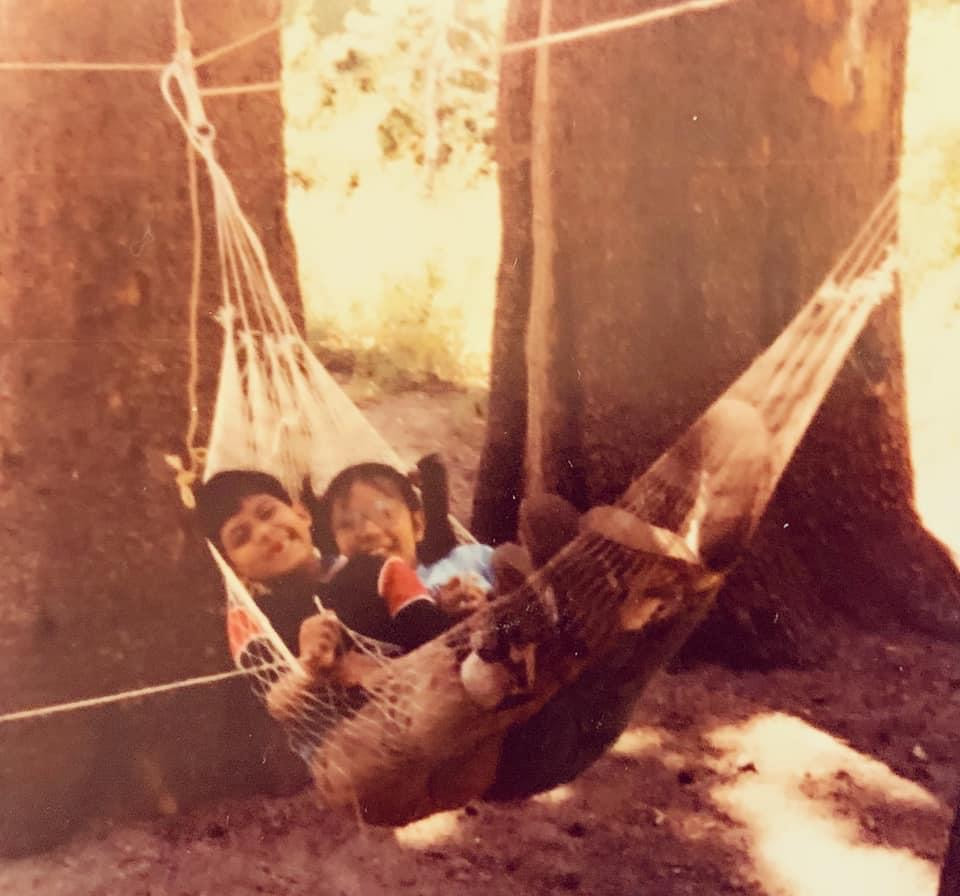

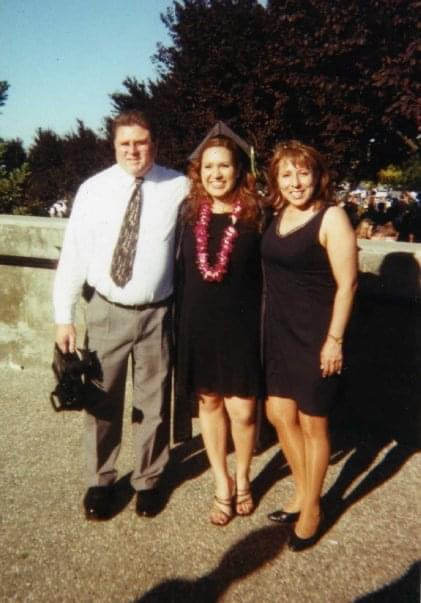

NANCY AIDÉ GONZÁLEZ THE POET: A PERSONAL NARRATIVE I was born on a hot day on July 3rd at 12:24 PM in the Imperial Valley to my parents, Amelia and Jose Luis González. I am told I came out of my mother's womb crying for life with a full head of black hair that stuck straight up. I was named Nancy because it means “Grace of God.” My mom felt that I was a gift from God because she almost lost me several times during her pregnancy. She was fragile when she was pregnant and skinny. To her, it was a miracle that I was born because she had endured a painful pregnancy. My middle name was chosen to be Aidé because my mom loved a novela that had an actress named Aidé in it who was intelligent and beautiful. Aidé is a variant form of the name Heidi which means “of a noble kind.” When I was born, both sides of my family were at the hospital. I was the first grandchild on both sides of the family. I was greeted with an abundance of love. My story is interwoven with the story of my mother and father. My mother, Amelia, was born in El Paso, Texas, and was raised in Mexico by her Tía Cuca. Her father and mother had separated when she was a baby. Neither her father nor mother could raise her, so she was sent to live with her Tía Cuca in a peach-colored adobe house in Delicias, Chihuahua. Tía Cuca took in my mother, her twin sister, Tita, and youngest sister, Armida. She and her sisters worked to earn their keep at their Tía Cuca's who had them clean, cook, and feed the chickens and pigs. There she went to school and attended a very strict Christian church. My mom came to the United States when she was 16 to live with her aunt. She worked in the fields of the Central Valley, picking fruits and vegetables. Then she moved to San Bernardino to live with her Tía Cholita. My mother always felt like an outsider. She encountered racism in high school. She was told to “go back to Mexico” and called a “beaner” by her classmates. My mom learned English in high school. My father, Jose Luis, was born in El Paso, Texas, and his family moved to San Bernardino, California, when he was a child. He did not know Spanish well. His father worked picking up garbage for the city as a sanitation worker, and his mother was a housewife. My father had four siblings. They were devout Catholics who attended church on Sundays. My father grew up playing baseball, chess, and wrestling. In high school, he was on the wrestling team. My father played saxophone in the school band. My mother and father met at San Bernardino High School. My mother was enamored with him. He was popular and considered handsome by the girls. They went on dates, but my mom's aunt was strict and would only let my mom stay out until seven in the evening. My mother was very religious and conservative while my father went to parties and dated other girls. After they graduated from high school, they continued to date and fell in love. Eventually, they got married in a church in 1976. There are photos of them at the wedding in an album. My mom wore a white dress made of lace and looked radiant. My father had a light blue bow tie and cummerbund. They are smiling in their wedding pictures while they cut the three-tier cake and have their first dance. In the wedding photos, they are full of hope and joy. They were young when they married. My mother had me a year later when she was 23 years old. She decided to go to junior college. My father worked at a carpet business for a while, laying down carpet in homes. My brother, Michael, was conceived two years later. Then my father started to work for the Santa Fe railroad. He began traveling to lay down tracks and fix the railroad tracks in different cities. My brother was born when my father began working for Santa Fe railroad. Then one day, my father injured his back, laying down the tracks for the railroad. The doctor gave my father prescription drugs for his back pains. The prescription drugs were not enough. My father turned to illegal drugs and alcohol to escape the pain. He began hanging out with people who did illicit drugs and became an addict. I was three years old at the time. Once someone becomes addicted to drugs, their lives change, and priorities shift. The addiction takes over, the person's personality changes, this is something I learned as a child. My father's addiction affected our family. My mother did not allow drugs in our house. My father was angry, jobless, and in pain. He would leave my mother, brother, and me for weeks, then months. Each time he returned, my mother and father would argue. My father would beat my mother. I would hide in the closet among the softness of clothing in the darkness. My brother would be crying in his crib. After my father beat my mother, he would leave the house as quickly as he arrived. The door would slam and shake the house on F Street. The engine of his yellow Duster would rev then speed away. I would come out of the closet to find my mother on the floor. She usually had a black eye and was bleeding from her nose. I would lay on the floor and hug her. We would cry together. Then my mother would eventually get up off the floor. She would clean her face and put ice on her eye. We would sing Christian hymns until we were tired. A few days later, my father would come home and beg my mother for forgiveness on his knees. He would promise he would change and cry. My mother would forgive him. For a week, there would be peace. We would go to church together. My mom and dad would hold hands while watching TV. Then my father would leave. The last time he left, I was five years old. He called my mom from a crackling payphone in September 1982. He told my mom that he was going to make a lot of money on a business deal. The money was going to change our lives, and everything was going to improve. A few weeks passed, and my father was found with fifteen bullet holes in his chest. Joggers in the Arrowhead mountains discovered his body in the bushes. The autopsy report indicated the last thing he had eaten was blood oranges. The police did not investigate or look for who killed my father. Due to the condition of my father's body, at his funeral, the casket was closed. I remember people at the funeral whispering while looking at me, “Do you think she knows she won't see her father again?” I remember staring at the black and white tile of the funeral home while a woman from our church sang “Amazing Grace.” I understood that my father was no longer alive, and I would never see him again. A recurring nightmare during my childhood was that my mother and brother were in a car accident. In my dream, they were in the yellow Datsun driving by in front of the house on F Street in San Bernardino. Then a semi-truck would come out of nowhere and crash into the Datsun. I would witness the crash in slow motion. In the dream, I would want to move from the porch to run towards them, but I could not move. I would be frozen, and when I screamed, nothing would come out of my mouth. I would wake up in a sweat, unable to move. I learned early on that words had power. I learned that the words my father yelled at my mother hurt her. I learned that the words of the lullabies my mother sang to me soothed me. I learned that lyrics in music I listened to by the record player could move me to dance. I learned in church that the words of the Bible were important. Words could build up or tear down. They could hurt and create invisible scars. My mother taught me my letters and numbers when I was four years old. She was in junior college and then attended San Bernardino State University. She wanted to be an elementary school teacher. She worked as a teacher's aide when I was in kindergarten while going to University. My mother would read books to me. I loved when she read me Goodnight Moon, Curious George, Little Red Riding Hood, and Five Little Monkeys Jumping on the Bed. I would ask her to read the books over and over. When she took me to the library, I was overjoyed to pick new stories that ignited my imagination. I struggled with reading in first grade. It wasn't until mid-first grade that I was taken to the optometrist. I had acute astigmatism and chose glasses with dark purple frames. I was delighted to have my glasses because, for the first time, everything was clear. Then to my dismay, I wore the glasses to school, and children made fun of me. They called me “four eyes,” and a boy told me, “You look ugly.” I sobbed in the bathroom all recess, and when I got back to class, I shoved my glasses to the back of my desk. I didn't wear my glasses at school. However, I needed my glasses to see, so I did not know what was going on in class. I couldn't see the letters on the board; everything was a blur. I disliked school, and I would daydream. I was seated in my chair in the classroom, but my mind was somewhere else. I would imagine being “Wonder Woman” and sliding down rainbows. It wasn't until third grade that I began to wear my glasses at school. I learned to read in third grade because I could actually see the words on the page without squinting. I had a reading anthology that my teacher sent home with me. I would practice reading every night with my mom or stepdad. One of my favorite teachers was Mrs. Whitfield. I had her for both fifth and sixth grade in El Cajon, California. She had us read Johnny Tremain, which is an historical fiction novel written by Ester Forbes set before the American Revolution. I remember that Johnny hurts his hand as a silversmith and could no longer use it. I felt empathy for his character, who had one hand and had a love interest named Cilla. It was the first young adult novel that I read that moved me. After reading Johnny Tremain, I became an avid reader. I would go home and read until it was time for me to go to sleep. Mrs. Whitfield also had my class memorize a poem a week. I remember we had to recite poetry to her and get graded. I memorized “Eldorado” by Edgar Allen Poe and “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost. She also let us pick poetry to read in front of the class. I was timid and I remember I chose to read “Let America Be America Again” by Langston Hughes in front of my class. I was only 12, and I did not fully understand all the concepts the poem addressed. I remember the line, “Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed-…” I remember shaking while reading the poem, each word was loudly spoken with conviction. The class clapped after I read the poem, and Mrs. Whitfield said, “Nancy is a poet!” Mrs. Whitfield believed in me and pushed me out of my comfort zone. She expected a lot from me as a student, and I excelled in her class. She made me feel seen. She awarded me a student of the year award in six grade. I don't think there is an exact moment that one becomes a writer. I just know that I liked to write. I remember writing a short story about a grandfather and granddaughter in seventh grade. My English teacher read the story to the class and said I was talented. After class, he took me outside and told me I should consider going to college. I told him I planned on going to college when I grew up. My mom and stepdad had ingrained the idea into my mind that I was going to college when I was six years old. My mom would take my brother and me to daycare to attend afternoon classes at San Bernardino State University. After class, my mom would let my brother and me run in the grass. My mom met my stepdad, John, in a Mexican history class. They were friends at first then they began dating after my father passed away. I did not trust John when I met him. I would not talk to him and did not make eye contact with him. Then he slowly became an integral part of my life. He would take my mom, brother, and me to pizza. He would babysit my brother and me. My brother and I did things with him that we were not allowed to do when my mom was around, like jump on the bed and dance. He took us to have chili dogs for breakfast. He told us dad jokes, and he still does. My stepdad accepted my brother and me as his own. John and my mom got married when I was nine years old. My brother and I were in the wedding. I was the flower girl, and my brother was the ring bearer. My mom and stepdad have been married for thirty-four years. It is from them that I know how love can change lives. In high school, I would write in a journal about my thoughts and feelings daily. I took Honors American Literature, where we read The Scarlett Letter and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. I took Honors World Literature, where we read Things fall Apart by Chinua Achebe and other African literature. I never saw myself in the books and stories that I read until my sophomore year at California State University, Sacramento. I took a Chicana Literature course taught by Professor Graciela B. Ramirez who assigned books by Chicana authors that impacted my life. I read Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza [1987], a semi-autobiographical work by Gloria E. Anzaldúa. I read Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma by Ana Castillo. I read This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, the feminist anthology edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa. I read The Moths and other Short Stories by Helena Maria Viramontes. I devoured these books because I saw myself in the essays and literature. I found myself and my culture described within the pages on these books, and it was empowering. It was the first time in my life that I thought I could be a writer. I was published in Calaveras Station, the literary journal at Sacramento State. I was overjoyed when I saw my poem in print. Years went by, and I became an elementary school teacher. I would write poems in journals and napkins, but I never shared my work. It was not until 2011 when I decided I was going to take my writing seriously. I became very depressed because I wanted a child. I had been trying to conceive a child for a year. I have polycystic ovary syndrome, and I was put on metformin by my doctor. It made me ill, but I stayed on the metformin. Then one day, my mother said, “I hate seeing you sad. Perhaps you should accept that you might not ever conceive a child.” I contemplated this idea for a few weeks. Then I decided that if I could not conceive a child that I would give birth to thoughts and words in the form of poetry. Poetry brought me back to life. I began writing poems and joined Escritores Del Nuevo Sol. At my first meeting, I read a poem about my female ancestors called “The Ones that Live On.” It was my soul that urged me to write the poem. Francisco X. Alarcón was a member of Escritores Del Nuevo Sol; he encouraged me to keep writing. Francisco X. Alarcón had a significant impact on me as a poet. He asked me if he could publish my poem on Poets Responding to SB1070 on Facebook. There, on Poets Responding to SB1070, I met other writers who were activists from across the nation. Joining a community of poets helped me gain confidence and discover my voice. I also joined the Sacramento Poetry Center and began hosting a poetry reading series called Mosaic of Voices for three years. I met brilliant poets while hosting the reading series. The readings were on Sunday afternoons; they became like church. Each poetry reading was spiritually and intellectually moving. I began submitting my work, and my poems were published in several literary journals and anthologies. My poetry friends became like a second family. When I begin writing, I don't know where the poem is going or what will spill out onto the page. Sometimes I write poetry, then take a few lines and write another poem. Other times, a whole poem will come to me in the middle of the night, and I will get up and write it. Poetry that comes to me in the middle of the night rarely needs to be edited. Some poems I revise and re-edit until I feel they are done. I know when a poem is done when I feel it in my heart that there are no words I want to change or images I want to insert. Writing allows me to explore my emotions and communicate ideas about the world around me. Poetry has helped me heal and has forced me to deal with pain. It has helped me understand my life experiences. It has helped me forgive others and myself. I have written poems about my father and my infertility. It has helped me transform into a more introspective individual. Part of being a writer is observing and experiencing each moment. I notice the smallest things, dust in the air, the smell of earth, and sunshine through leaves. Poetry allows me to take my pain and make it into something heartbreakingly raw and beautiful. My soul moves me to put pen to paper and give birth. THE POETRY OF NANCY AIDÉ GONZÁLEZ: “…something heartbreakingly raw and beautiful” La Virgen de Las Calles for Ester Hernandez She stands on the busy street corner selling delicate red and white roses hugged by baby's breath and luminous cellophane resting in a once discarded plastic bucket. She understands the innate beauty of roses, their fragility their fragrant hope as they grow slowly from bud to emerge embracing change, as they flush into full bloom. She knows of piercing thorns and truth of crossing barbed wire borders. She understands the prickling sting, the aculeus of being an outsider. She wears a large sweatshirt with USA emblazoned in block print across her chest but she misses Mexico and the small town she was raised in. A red and green rebozo hangs down upon her head shielding her from the fulgent sun, a gift from her mother, a reminder of home. People stride past her lost in their own thoughts hustling to work, on pressing errands, wandering down the tangle of the Los Angeles landscape. She is La Virgen de las Calles, waiting with a heavy heart, full of yearning, dreaming of new horizons, a fountain of humble tenderness and abounding love. La Virgen de las Calles comprehends the nature of roses, their vulnerability their need for nettle. Rose Ranfla Riding in the ’63 Impala cruis’n el corazón del barrio passing by carnalitos y carnalitas running through sprinklers abuelas y abuelos on the porch talk’n about the old days cholos playing handball at the high school women in the beauty shop getting their hair did rollin’ past taquerías panaderías heladerías Bumping I’m Your Puppet La La Means I love You Thin Line Between Love and Hate Sabor A Mí through the streets of Califaztlan Chrome spoke wheels spin low and slow variations of pink paint layers glisten hard top covered in a garden of hand painted gypsy roses lean back upon velvet pink interior flip the switch hit the hydraulics dip and raise dip and raise hop hop hop off the ground in the intersection the journey has just begun let’s chase the immensity of the moment in estilo. Serenade I become earth’s remembrance of everything creviced skin of red rock endless pregnant season toothless silence I want to understand this world, your scars stay cradled by tree arms delve in splinters my womb is filled with clay barren it throbs I want to say many things but my words are trapped in caverns where bats hide from redundancies no one told me of the gritty essence of the residue that settles Black star dying innumerable deaths in this life we have come here to the waters we are he and she or man and woman scent of copper and jasmine we sip smoldering gravity separated space fills a serenade in golden afternoon unborn twins sob otherworldly whimpers timeless they can be heard by the bees and ants they enter this wasteland we inhabit nameless they will remain, my infants Adrift we are. Come to me. I am alone. wild horses turnover the headstones take my ovaries spine skull take the truth I search for in crushed leaves, in the fading contrails of fading light. Zapata y Frida By chance they meet at a bar she drinks tequila shots she wants to be life itself he caresses his gun he longs for uprising. he strokes his mustache, his wet lips glistening she touches her brow, her eyes aflame they speak of monkeys and flowers, of war and borders in the corner they become the world itself, spinning off axis they laugh loudly and don’t notice people staring “Take me away,” she says. II She places her hands on his face studies his indigenous features examines his eyes “I know you” she says. “I have known you all my life. You will cause my slow death.” III She unbraids her hair her pink ribbons fall to the tierra he take off her embroidered dress he places his hands upon her small breasts they devour each other’s skin thrusting and precise piercing moaning until night melts into brightness there are no promises made upon the wet grass after she places her head upon his chest and hears the drum of his heart “You will remember me.” she says. IV They ride horses through Morelos near sugar cane fields “It is better to die on your feet than live on your knees,” he says. “Death knocks at my door,” she says. “I have no mercy,” he says. “Please have mercy on me,” she says. VII The next time they make love she unhinges him touches the wilderness with abandon hunger drives them deeper into the topography of vermillion desire VIII An eagle sits on a cactus and watches them dance to corridos she pulls him close with her rebozo “We are home,” she says. IX That night she has a dream she is in the forest alone she is a deer and arrows puncture her flesh she awakes sobbing and gasping paint splattered on her face She reaches for him. “No llores,” he says. “I want to be your soldadera,” she says. X He vanishes in the middle of the night he leaves her a rifle with a rose in the barrel she takes her brush and paints. Railways Smell of dirt and sweat Mingled with whiskey and cigarettes the train resounds, he is home. All day he mends railroads comes home & takes of his dusty boots, the sour aroma of twilight. I watch his face think of the softness of the figs growing in the backyard, play with dolls. He calls me outside talks to me as he smokes a joint about constellations and the dangers of night, I tell him of the butterfly I caught and set free. The red porch paint peels, nearby the cactus grows entangled this is our small space his jagged hand caresses my face, above a shooting star scars the sky. Then he and my mother fight A blur of fists, blood his departure marked with dissipating smoke. I don’t want to know the details of where he went or how he felt as all those bullets punctured his flesh. All I hear is his distant voice on the cracking phone line saying, “I will be home soon.” On the way to the funeral we stop as the train roars car after car after car speed by weight & rhythm of wheel on steel, he has gone home. Foreigner I am a foreigner in my own country there is torment in the disconnection, I examine the geometries of mountains and plateaus pass by clamorous rivers, the land remains the same. The land remains the same in the mirror, reflection my face is my own my wide brown eyes my carefully drawn red lips, the world has changed. The world has changed, I send a letter to a good friend Wait for an answer that might never arrive, the mailbox is empty I must fill my own emptiness. I must fill my own emptiness the dirty laundry piles up, politicians recite alternative lies on television lying has somehow become the norm, I march with millions in protest against injustice raise my voice for the voiceless, raids round up “unauthorized” immigrants to be sent to Mexico, there is an unraveling of fear and hate. There is an unraveling of fear and hate my soul knows the unsayable, I drive to work and back home throw things on the ground to see how they fall, pick up wilted flowers try to revive them, find a dead seagull on the path blood encrusted with dirt broken wing hanging, I search for the bare skinned essence of light within darkness. I search for the bare skinned essence of light within darkness, at the park a small girl holds a red balloon she becomes distracted by laughter lets go of the string watches the balloon float to meet the sun, I want to peel the sun lay my fingers on permanence. I want to peel the sun lay my fingers on permanence, rays illuminate a thick black arrow tattooed on the cashier’s forearm, I want to follow the arrow to where it might take me, so I may arrive at the unseen, become connected. I am a foreigner in my own country the land remains the same yet my world has changed, memory filters through lace wings those I thought I knew, have become strangers. Expedition of the Heart for Christina Fernandez A woman’s voice whispers in español there is no silence during daylight hours only memory arranged and scattered days that become years map charted life air thick with absence, un canto. 1910, Leaving Morelia, Michoacán Through Michoacán the fishermen throw nets into clear waters fish sink heart sick light is submerged revolution leaves dust thick insurgent shapes arc She clasps her hands gazes out in the womb a child stirs door-heart creaks in the empty house resolve ripens becomes honeyed she has died and has been resurrected she must leave the river that sings now the monarch beckons. 1919, Portland, Colorado Stains have been scrubbed in laundry detergent bleached in stark bubbles that shine like prismatic marbles creating rhythm on washboard ridges soft hands massage grime, bitterness Wooden pins fasten three shirts and a bed sheet alabaster they flap in the breeze She knows she must travel lightly leave segments to soak to lift to float feathered and bask in the impermanent sunlight. 1927, Going Back to Morelia What is known, will be known what I take in this black chest is not mine, it is ours. These tracks will take me back to the smell of copal and agave nectar where I will kick the scorpion and hold the snake I will invoke la Virgen. I clasp these words written on crumpled paper words that have carried me through vacant terrain I hold these needles which I will use to thread together shreds mend each emotion filament by filament. I am not who I was you will know me anew I will rename each radiant blade of grass each distant storm after you. 1930, Transporting Produce, Outskirts of Phoenix. Arizona Be careful not to bruise the apples that is not to spoil the flesh I was told to twist the stem gently leave the tree as it is fruit is placed into wooden crates, carried to the truck We were told there would be water and a bathroom there wasn’t we were told we wouldn’t be sprayed with pesticides, we were we were told many lies. We watch majestic seasons clinched in foliage shift follow the crops in old cars where they lead we are strangers yet friends we are hombres y mujeres always leaving behind something someone each other always searching orchards and rows for distant secrets, trying not to bruise. 1945, Aliso Village, Boyle Heights, California I trust one and perhaps I trust none I wear an apron sweep and mop the houses of others, then my own I clean mirrors so I can see what is and what is not wipe reflections with rags as solitude encloses After dusting, motes remain and gather these granules the soul accumulates. How far I have come, each sepia detail crisscrossing small daily miracles. 1950, San Diego Faith has brought me to where I am These things I touch with my two hands: a hot stove, pots, pans, a cup of tea, my children I belong to myself, to others. This space is mine this spot where the floor is illuminated and love collapses I need to tell you, you are enough you will leave pieces of yourself scattered through the world you will be drawn back by generations of madres, padres, hermanas, y hermanos you will envision your ancestors existed far removed from desolation that they were not lost You will scrape together details of their lives become the author of your history tell their stories with your words Our narratives will continue we will find our way home. © Poetry: Nancy Aidé González Nancy Aidé González is a Chicana poet, educator, and activist. Her work has appeared in Huizache: The Magazine of Latino Literature, La Tolteca, Mujeres De Maiz Zine, DoveTales, Seeds of Resistance Flor y Canto: Tortilla Warrior, Hinchas de Poesía, La Bloga, Fifth Wednesday Journal and several other literary journals. Her work is featured in the Poetry of Resistance: Voices for Social Justice, Sacramento Voices: Foam at the Mouth Anthology, and Lowriting: Shots, Rides, and Stories from the Chicano Soul.

Edited by poet and writer, and member of Círculo de Poetas y Escritores, Lucha Corpi, for Somos en escrito Magazine. ZHEYLA HENRIKSEN

PREÁMBULO: EN SUS PROPIAS PALABRAS: Niñez y Juventud de Zheyla Loor Villaquirán Nací en Portete, un pueblito ecuatoriano aislado y al cual sólo se llegaba en barco, Mi padre me registró a los 6 meses que viajó a la ciudad, el 20 de febrero de 1949. Creo que no quiso pagar la multa, así que todos mis documentos tienen esa fecha. Pero yo festejo el verdadero día en que nací: el 16 de agosto de 1948. Creo yo tendría 6 años cuando mamá dejó Portete, donde nacimos todos, con sus dos últimos hijos, mi hermano Manolo y yo, para vivir en la ciudad de Esmeraldas. Jamás volvimos, aunque siempre teníamos las maletas listas porque mamá decía que nos iba a mandar de vacaciones con una hermana mayor que vivía allí. A la ciudad sólo se llegaba por medio de un barco muy primitivo. El dolor de la muerte de un hermano de 16 años y por la causa que ya se nos la iba llevando el mar (literalmente porque mi hermano y yo pescábamos desde la cocina), mi mamá decidió abandonar el pueblo. Portete, sigue siendo un pueblito, pero al frente se ha construido un resort muy moderno. Con la marea baja se puede cruzar a pie del hotel al pueblito. Al subir el mar hay que usar una lancha. Que yo recuerde, estaría yo en 4to o 5to grado cuando comencé a escribir poesía. Casi todas mis compañeras de la escuela primaria eran mayores que yo y tenían enamorados. Supongo que sabrían que yo escribía poemas, por eso me pedían que les escribiera acrósticos para sus enamorados. No recuerdo los poemas. El único poema que la memoria recuerda es el de mi primer amor por un torero imaginario que conocí en la “plaza”. Con decirte que yo no tenía ni idea de lo que era amor ni tampoco de lo que era una “plaza de toros”. La única plaza que yo conocía era la que también llamábamos mercado. Así es que a mi toreador “lo conocí” en el mercado. Mi maestra no creyó que yo hubiera escrito ese poema, pero lo corrigió y recuerdo la palabra “contendor” supongo de “contender” que ella substituyó por la mía: Pasando yo por la plaza vi a un hermoso torero que por mí daba la vida que por mí daba su amor Estamos ya cara a cara vamos para mi casa que tengo todo arreglado para realizar nuestra boda Aquel torero garboso le tocó pelear con un toro de los más feroces que había El toro ya lo vencía cuando alzó la vista hacia mí y dijo: ¡oh morena! ¿aquí habéis estado? Sí, aquí me hallo mirando, Mirando cómo peleas por vencer a tu contendor Pero, ¿de qué me vale ese honor? Y así terminó mi vida con aquel torero que por mí daba su vida que por mí daba su honor. Mis hermanos mayores ya vivían por su cuenta y las mujeres ya casadas, pero todavía había dos hermanas que estaban en un internado estudiando en la ciudad. Allí nos fuimos Manolo y yo. Ya estábamos en edad escolar y por primera vez nos separaron. Me pasé todo el año llorando y por eso perdí mi primer grado. Mi escuela quedaba al frente de la de mi hermano, pero no estábamos juntos. Mi escuela primaria era monolingüe. En la secundaria teníamos un profesor que había aprendido inglés por sí mismo, así que nos enseñó “a traducir”, entre comillas porque en realidad era puro vocabulario lo que nos enseñaba. Cuando me casé, mi esposo decidió que debíamos visitar Portete. Tendría 23 años. En aquel tiempo sólo se podía ir en barco. Recientemente se construyó una carretera y dos sobrinos me han llevado las últimas veces que he ido a Ecuador. Emigré porque estaba casada con “un gringo” que pertenecía al Cuerpo de Paz, “Peace Corps”. Lo conocí en el 2do año de universidad, cuando mi profesor de inglés tuvo que viajar a los EE.UU. y buscaba un remplazo por un mes. Encontró al que iba a ser mi esposo en la calle y él aceptó substituirlo. Así lo conocí. Mi hermano y yo nos sentábamos juntos en la clase de inglés y le hacíamos bromas de su pronunciación en español. Todavía en Ecuador, nos casamos, y construimos una casa. Estudiábamos francés en la Alianza Francesa porque yo quería continuar mis estudios en la Sorbona. Mi profesor de francés, que también era el cónsul de Francia, me había seleccionado para que yo fuera la segunda estudiante de la Alianza que él mandaría. Mi profesora de literatura de la universidad había sido la primera becaria. Pero tuvimos un terremoto muy fuerte que hizo que el edificio donde teníamos clases se derrumbara. Como mi esposo pertenecía al Cuerpo de Paz y por estar casado conmigo ya le habían renovado dos veces su estadía, le dijeron que tendría que regresar a los EE.UU. Teníamos los dos 30 años entonces. Con el derrumbe del edificio terminó el sueño de ir a Francia. Y aquí estamos, en California. ENTREVISTA: EN PLATICA: Lucha Corpi (LC) y Zheyla Henriksen (ZH) LC: Zheyla, tuve la suerte, por primera vez, de oírte declamar tus poemas en público durante un recital de poesía en Sacramento, California, patrocinado por Escritores del Nuevo Sol en conjunto con Círculo de Poetas. Dijiste algo muy interesante a modo de preámbulo a tu presentación, y es que casi exclusivamente escribes “poesía erótica”. En general, cuando alguien, y en especial una mujer dice eso, creo que el público inmediatamente piensa en el sexo o acto sexual mismo. Aunque ya no tan a menudo, también consideran a la mujer amoral. No piensan en la sensualidad, la cual es producto de la imaginación. Es decir que el erotismo no es producto del cuerpo, enteramente, y puede no preceder o ser parte del acto sexual. Así mismo, consideran a los poetas (sexo masculino) como primordiales exponentes de la poesía erótica. Aquí mis preguntas con la idea de aproximarnos a tu propia definición de tu arte poético: LC: A tu parecer, ¿Cuáles son los elementos primordiales que definen la poesía erótica en general? ¿Y de qué manera se manifiestan estos en tu propia obra? ZH: Bueno, mira, no es que yo escriba exclusivamente poesía erótica, pero me inclino bastante a ella. Lo que pasa es que por haber quedado como finalista en el concurso internacional de poesía erótica en las dos veces que participé, me han dado ese título y yo me lo he apoderado. En cuanto a lo erótico como campo masculino, no lo veo desde la visión histórica sino desde el punto mítico-religioso. Me explico: Míticamente los ritos “orgásmicos” primordiales le corresponden a la mujer porque es ella la suprema dadora del placer. Entre muchos estudios, voy a mencionar sólo tres: The Great Cosmic Mother: Rediscovering the Religion of the Earth de Monica Sjöö y Barbara Mor, y en Sacred Pleasure de Riane Eisler, explican que fisiológicamente es en la mujer donde, exclusivamente, existe una conexión similar al trance religioso en el cerebro frontal y el cerebellum lo que permite el enganche al “neocortex”. Por eso en el acto sexual, la mujer experimenta un cierto trance espiritual, el éxtasis. Si observas tú la estatua de Bernini, El éxtasis de Santa Teresa, la contorsión y el relajamiento del cuerpo de la estatua es similar gesto del éxtasis sexual, (tuve la dicha de verla en W. D.C.) LC: De acuerdo. Entonces en todo esto, la mujer es la dadora del placer en la pareja! Y si es así, ¿Qué papel juega el hombre? ZH: Así es. Las investigadoras observan que en los ritos sumerios, el hombre es el objeto del placer. En los himnos a la diosa Inana, que hoy se consideran más antiguos de lo que se creía; a la mujer se la presenta como la dadora y conductora de la energía divina a través del sexo. Por tanto es también la creadora de la escritura sagrada llamada el Kundalini. Estos versos son los más bellos cánticos a la sexualidad. Sin ir más lejos, en el libro histórico como que es la Biblia, el Cantar de los Cantares contiene versos de tremendo contenido erótico. En ellos es la amada, la hablante, la que seduce y canta a su amado. LC: Hace muchos años que leí algunos de ellos, pero a escondidas. Ya sabes, la religión católica le prohíbe a la mujer leerlos. Y crecí en México, donde la iglesia católica manda. ZH: En realidad se piensa que estos versos pertenecían a libros míticos, pero con la imposición más tarde del patriarcado no pudieron eliminarlos, y más bien fue un caso de “co-option” política. La religión moderna los interpreta como un canto de amor entre el creyente y la iglesia. LC: Claro. La iglesia. La que a veces ve solamente por sus propios intereses y enriquecimiento, y la liberación sexual de la mujer no le conviene. ZH: Al imponerse el patriarcado lo erótico y la escritura erótica pasó a ser dominio del hombre y desde entonces él es el que puede cantar a la sexualidad, al amor, al erotismo no sólo de él sino de la mujer. ¿Te parece esto justo? LC: Claro que no. Pero en estos casos nunca se trata de justicia, ni siquiera de caridad, sino de conveniencia y poder. ZH: En lo que respecta a la mujer latina. El hombre le ha impuesto la modestia y el silencio, según las editoras del libro Pleasure in the Word: Erotic Writing by Latin American Women, e indican que la política del patriarcado cercenó el derecho que desde tiempos prehistóricos le correspondía a la mujer como dadora del placer y de la escritura. LC: Es decir que la mujer, al escribir cualquier tema que se le tilde de “erótico,” está aceptando que es la mejor exponente del erotismo. Pero el varón no puede aceptar la competencia, aunque hay muchos que lo ponen en términos de hacerle un bien a la mujer al reprimirla, Por el bien de la raza humana. Pero eso ya va cambiando debido a movimiento feminista. ¿Cuál es tu parecer? ZH: Lo que las poetas, y me incluyo yo entre ellas, están haciendo es recuperar su sexualidad, al crear su propio lenguaje para expresar lo erótico, deshaciéndose de la palabra-masculina. Y como me inclino mucho a lo mítico, incluso en mis investigaciones, tengo la tendencia de buscar y encontrar fácilmente símbolos míticos. Considero que en nuestro inconsciente colectivo se conservan esos mitos que son actualizados por el rito de la escritura erótica. Según Cassirer y Jung, la escritura, y especialmente la poesía, es el rito por el cual se actualizan los mitos. Ahora te voy a contar una anécdota personal. La primera vez que fui a una conferencia a la universidad de Louisville, Kentucky donde me aceptaron tanto en ponencia como en poesía, me encontré por primera vez en el panel de poesía a dos poetas eróticas, Nela Rio e Ivonne Gordon, compatriota esta última. Por primera vez leía mi poesía erótica y con tanta vergüenza que agachaba la cabeza. Luego me dice Nela, Zheyla, no debes de avergonzarte de leer tus poemas eróticos y de allí me invitó a otra lectura en Washington D.C para poemas del cuerpo y más tarde, a otras conferencias y poco a poco fui perdiendo la vergüenza que ahora me siento una “sin vergüenza”. Nela ha sido una de las poetas más generosas con la que me he encontrado en el camino de las letras, ella fue la que me dio información sobre el Concurso Internacional de Poesía Erótica en la que le habían otorgado una mención honorífica especial. LC: ¡Qué linda y generosa Nela! No tuve el placer de conocerla, pero tuve el gusto de conocer y compartir con Ivonne Gordon en San Antonio. No recuerdo bien el nombre de la conferencia, pero si el tema: Mujeres Poetas del Mundo Latino. Había otras grandes poetas de América Latina, al igual que Norma Cantú. ZH: Poema a Nela Nela contigo puedo jugar a las rayuelas cantar una ronda infantil "qué quería mi señorío matun-tiru-tiru-lán" -queremos ser poetas y cocineras, matum-tirun-tiru-lán Nela contigo vuelvo a la infancia con una canción de cuna "duérmete mi niño que tengo que hacer" lavar estos versos ponerme a comer Nela de niñas yo te enseñaría el "tun, tun ¿quién es? el diablo con los siete mil cachos o el ángel con la bola de oro" que quiere una fruta o cinta para ponerle colores colocarla en un moño Nela Correríamos nuevamente una calle cualquiera pero tomadas de la mano para robar una estrella. LC: Es como si se hubieran conocido tú y Nela desde la niñez, jugado juntas —desde siempre. Bello. Cambiando un poco el tema. Veo que has publicado tu poesía en un sinnúmero de antologías y revistas, y en ediciones de tus libros. El único de tus poemarios que tengo es el último, Confesiones de un cuerpo/Confessions of a Body, editado por la Editorial Académica española en el 2019. ¿Cuáles son los títulos de tus otros poemarios? ZH: 1) Pedazos, los recuerdos/Shattered Memories 2) Caleidoscopio del Recuerdo/Kaleidoscope of Memories 3) Confesiones de un cuerpo: Estaciones de Pasión/Confessions of a Body, Seasons of Passion. LC: Me has dicho que conociste a Phan Thi Kim muchos años después de que terminó la guerra en Viet Nam. Pero escribiste este poema muchos años antes. ¿Qué te hizo escribirlo? ZH: Otro ejemplo de la violencia contra la mujer ya desde niña, está fotografía icónica, en especial de una niña vietnamita desnuda, huyendo, de la guerra en Viet Nam. El poema que yo le escribí: “PHAN THI KIM”, fue publicado en 2003 en la exposición de poesía Outspoken Art/Arte Claro, dedicado a la eliminación de toda forma de violencia contra la mujer. PHAN THI KIM You have forgiven us. Your fragile body running naked stuck in my mind. For years the picture has been encrusted in my retina, behind the infernal dust that burned your body half. Nic Ut save your image for the world to see his crime. I still don’t understand why man has created war. Tiny body, open mouth arms flapping horizontally, Behind, in front, in the center you, the Christ, the city. And still the world goes on the same crime for ever and ever. Phan Thi you are thirty three now and you came to forgive us. ********** LC: Ha sido un placer platicar contigo, Zheyla. Mil gracias por tus versos. Un cálido abrazo. © Poetry by Zheyla Henriksen ARTURO MANTECÓN |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed