HusksAbuelita tells me that I was born in the month of Tlaloc: Part jaguar, part thunder and rain—grown like corn, in a smoggy valley downstream from the Iztaccihuatl. There, we knew how to cook for the dead: tamales sweet as suffering. With molcajetes, we mashed hearts stuffed with the blood of truths omitted while loving. I don’t remember the bullet that split Julio’s skull. But, imagine Mother hypervigilant for the sky falling. Death threats, caseloads of Bacardi, comida cold. Joy coagulates, like cars on the periférico. Finally, we see corruption’s fangs taller than any volcanos. Negrita is left at the pound. All night, camote carts cry. Then came the trunks, the take-only-what-you-need, leave the snow on the Ajusco, take Juanita Perez. Feel the bloody slice of the interim between indigena and immigrant. Here, my estadounidense classmates pretend I don’t exist. Abuelita dies. Even Tlaloc forgets me in this blurry desert: Santa Anas in our eyes, on the stingy side of survival. Somedays, we even let ourselves feel the grinding of the stone, identity sifting, the flattening of the rolling pin. Next time, consider keeping all the husks when you peel me. Nursemaid MagicFear runs like a headless chicken flapping into you at the market, when you least expect it to— wings tossing up dirt long after the machete has been wiped clean of blood. The blade is our phone. It swings at safety every time the calls arrive: “Los vamos a fusilar!” Meanwhile, Mami draws lines in the rugs pacing—she squawks, her feathers awry. Some will grab the rosary, others the gun. There is no time to wait for pricy milagros in the Plaza de la Conchita. But I was with Juanita making maza and, I swear, she left the virgencita on her gold throne, and summoned the pumas, monkeys and nāhuallis down from her verdant Oaxacan hills instead, right into our kitchen in the big city. She wove protective spells into my black braids, combed out my anxiety with her whispery Náhuatl, took me straight to the moon of her smiling face. Some will burn copal, others learn about battle from the zing-zing of hummingbirds. It’s no wonder Mami, to this day, though safely tucked into a California suburb, refuses to answer her phone: She didn’t have a nursemaid like my Juanita. The Body RemembersMy Abuelita nearly died in the fire that ate her songbirds, in the city Dad came from-- where he played the violin. Maybe it was cigarettes, maybe spontaneous combustion. We don’t talk about those things that happened in Juarez, where youth was bought and sold, like trinkets at the border. But ask my mother and she’ll tell you how Alzheimer’s brought it all back. How the body resurrects wounds before it dies: harkens back to terror through touch. After the brain falters, after fighting, escaping, crossing, sweating, surviving. You still die under a conquistador’s swinging sword. I prefer fire.  Katarina Xóchitl Vargas was raised in Mexico City. She and her family moved to San Diego when she was 13, where she began composing poems to process alienation. A dual citizen of the United States and Mexico, today she lives on the east coast where—prompted by her father’s death—she’s begun to write poetry again and is working on her first chapbook. Somos en escrito is delighted to be the first to publish her writings.

0 Comments

“Por escrito” Lucha Corpi (LC) entrevista a Graciela Brauer Ramírez (GBR), Catedrática jubilada de la Universidad Estatal de California en Sacramento. Poeta y narradora chicana, y trabajadora cultural incansable. Miembro de “Escritores del Nuevo Sol” en el Valle de Sacramento y de “Círculo de poetas & Writers” en la Bahía de San Francisco, con sede en Oakland. AZTLÁN – El lugar de las garzas LC: Querida Graciela, cómo se ve claramente, en la portada de tu libro están estampadas las garzas, aves que normalmente habitan a orillas de los ríos en California y en México: Algunos de los ríos más caudalosos se encuentran en el sur de México y precisamente en el estado de Veracruz y cerca de la Ciudad de México de donde eres originaria. Me fascinó ver que tu obra comienza con una descripción del Río Americano (the American River) que atraviesa de lado a lado la Cd. de Sacramento, capital del estado de California. Según la leyenda indígena mexicana, AZTLÁN era el lugar de origen de las varias tribus pre-colombinas, las que poblaban el continente de América, desde Alaska y Canadá hasta Tierra del Fuego en Sudamérica. A primera vista se podría también decir que EDUCACIÓN: Una Épica Chicana de la catedrática, poeta y narradora, Graciela Brauer Ramírez, es un libro de texto histórico. Ofrece una visión y cronología histórico-política de acontecimientos que se suscitaron en la Cd. de Sacramento, capital del estado de California, durante las décadas de 1960 a 1980. Al mismo tiempo, ofrece una vista panorámica del movimiento socio-político y pro-derechos civiles del pueblo México-americano en EE.UU., es decir de la población que se autodefine políticamente como chicanos. De una manera más general, bosqueja también el impacto de los logros de esta población, desde entonces hasta la fecha. Desde el punto de vista literario sigue las reglas de una epopeya clásica, es decir como lo fueran la Odisea o Ilíada en la antigüedad. Es un relato en verso y trata de las hazañas de héroes en tiempos de guerra y en defensa de su pueblo, su historia y cultura. Más aún, es la infra-historia de una familia californiana, con fuertes lazos culturales, literarios e históricos, con México y el sudoeste de Estados Unidos. Gracias. Graciela. Lucha Corpi Entrevista y plática: Lucha Corpi (LC) y Graciela Brauer Ramírez (GBR) en conversación. Influencias: En familia o comunitarias: LC: Tu obra culturalmente es parte de una tradición oral, pero lo es también de la literaria. Es en verdad, Una Épica Chicana, y una obra monumental. ¡Enhorabuena, Graciela! Ahora, cuéntanos un poco sobre tu niñez y adolescencia en familia. Sabemos que tu padre fue de gran influencia en ti, quien estimuló tu sed intelectual por el conocimiento y la lectura. Aprendiste a leer a los cuatro años. Entiendo que tu convivencia con otros parientes, en ambos lados, también fue muy importante. En familia, aparte de tu papá y mamá, ¿Quiénes más fueron de gran influencia en ti durante tu niñez? GBR: Como digo en mi libro, Una épica chicana, por las noches, en familia, nos juntábamos en el patio y cada uno decía poesías o contaba historias. Por ejemplo, a mi tío Homero le gustaban las historias del mar y de barcos. Después fue marinero. Mi tío Sergio siempre nos contaba la misma historia sólo le cambiaba los nombres de los personajes. A mí me subían en una silla y recitaba: “Mamá, soy Paquito, no haré travesuras…” Y también una que dice: “Guadalupe la Chinaca va en busca de Pantaleón su marido…” Dado que a los 2 o 3 años yo no podía todavía hablar bien, recitaba este verso a mi manera: “aupe anaca busca a neon maido…” Mi tía Elena, aun cuando ya estaba yo grande, se burlaba de mí imitándome, pues a esa edad temprana no podía yo hablar claro, pero, según yo, ya recitaba. También mi tía me decía que cuando terminaba yo les pedía aplausos al “púbico” (el público). LC: Me haces reír. Muy divertido. Ya entrando a la secundaria, ¿seguiste recitando poemas en público? GBR: Claro que sí. Ya de estudiante, en la secundaria, recitaba en concursos y en uno de ellos gané el primer premio al recitar de memoria el poema “Los Motivos del Lobo” de Rubén Darío el gran poeta de Nicaragua. Hasta la fecha, ya en mi vejez, aún recuerdo todo este poema tan largo. LC: Entonces, en cuanto a los lugares que fueron importantes en tu desarrollo durante tus años tempranos, sabemos que naciste y viviste en la Ciudad de México y que sufriste los calores y el bochorno del trópico en el puerto de Veracruz. En el prólogo de Educación: Una Épica Chicana, JoAnn Anglin, gran poeta y narradora, a quien también tengo el gusto y la honra de conocer, nos da algunos datos personales tuyos, pero bastante esquemáticos. LC: Si te es posible, cuéntanos un poco de ti, de tu vida personal antes de unirte al cuerpo docente de la Universidad Estatal de California (California State University at Sacramento-CSUS). GBR: Las gentes que tuvieron más influencia en mi infancia fueron mi papá y mi tía abuela Juanita. El me introdujo a la lectura, al grado de que cuando fui al kínder ya había leído varios libros de cuentos que él siempre me compraba. Mi tía abuela Juanita tenía una tienda de abarrotes a media cuadra de nuestro apartamento. Ella tenía su recámara arriba de la tienda. A veces ella me cuidaba o cuando iba a la tienda inmediatamente subía a su recámara pues ahí tenía muchos libros. Ahí leí: Corazón Diario de un Niño, Las Mil y Una Noches y muchas otras obras que aún viven en mi mente y que me han ayudado a sobrevivir. Un día mi tía me sorprendió mucho cuando me regaló estos dos libros y algunos más. También mi papá. Él era militar, y por algunas horas, también valuador en la mayor casa de empeño controlada por el gobierno. A veces tenían subastas y la mercancía que quedaba la repartían entre los trabajadores. Esta era generalmente de libros, los cuales él traía al apartamento. Entre esos libros leí, con ayuda de adultos, La Vuelta al Mundo en Ochenta Días, El Jorobado de Nuestra Señora de París y muchos más. Fui muy afortunada. LC: Nos has contado que debido al trabajo de tu papá, quién era militar, viviste en diferentes lugares. ¿Cómo afectó el pasar tu infancia y adolescencia en comunidades tan diferentes una de la otra? GBR: Primero, era una bebé y mientras que las mismas personas me cuidaran, no había problema. Después, cuando contaba con cuatro años, mi papá me ponía en el tren los viernes por la noche y mi abuelito me recogía en el puerto de Veracruz en la mañana del sábado. El regreso era viaje opuesto, por supuesto, de domingo en la noche a lunes por la mañana. También pasaba todas las vacaciones en la costa del Golfo de México, que era la costa veracruzana. Vivir en el puerto de Veracruz fue para mí una experiencia muy afortunada pues mi abuelito era una persona muy educada al haber estudiado en el seminario; había leído mucho. Con él aprendí bastante. También en Veracruz vivían mis tíos quienes eran muy adeptos a las poesías. Mi tío Carlos, por ejemplo, sabía muchas de ellas de memoria. En las noches nos recitaba versos de sus autores favoritos como Díaz Mirón, poeta veracruzano. Mi tía Estela recitaba en las escuelas. Aún recuerdo una de sus poesías favoritas que dice: “…espera la caída de las hojas.” Mi abuelito y su hijo mayor trabajaban en el ferrocarril me conocían y me querían bastante. A menudo, ellos me llevaban de viaje. Durante mis viajes la tripulación del ferrocarril me cuidaba. LC: Cuéntanos también de tu familia materna y de tu educación formal y adolescencia GBR: Cursé la primaria en El Colegio de San Ignacio de Loyola comúnmente conocido como Colegio de las Vizcaínas, una escuela católica en la Ciudad de México. Mis padres se divorciaron cuando yo tenía menos de un año. Mi papá tomó la responsabilidad de criarme. Él era militar así es que yo crecí regimentada, cosa que siempre le he agradecido pues aprendí disciplina, algo que me ha servido toda mi vida, y que él hizo con mucho amor. A los 15 años me fui a vivir con mi mamá. Ella era una famosa cantante de música ranchera. Mi vida con ella era excitante pues me llevaba a los teatros y estaciones de radio en donde conocí artistas famosos de aquella época. Por otro lado, ella era una persona muy extrovertida y se impacientaba mucho conmigo por ser yo sumamente introvertida. Con ella viajé en sus giras por muchos estados de México y lugares en los Estados Unidos como las ciudades fronterizas de El Paso, Texas y San Diego, California, además de Los Ángeles en California, entre otras. Desgraciadamente mi mamá y yo éramos demasiado diferentes. Ella era una feminista que a los 40 años se hizo torera aficionada; yo vivía dentro de los libros. Con mis padres crecí en dos mundos completamente opuestos. Sin embargo, en ambos mundos, todas mis experiencias fueron muy buenas. LC: En esta entrevista quiero hacer resaltar no sólo tu trayectoria poética-literaria sino también tu participación en el movimiento pro-derechos civiles y humanos del pueblo chicano en Estados Unidos. Al leer tu obra, me doy cuenta que tú fuiste testigo y participante en muchos de los acontecimientos que describes en tu libro durante “el movimiento chicano”. Cuéntanos sobre esta importante época de tu vida. GBR: Mi participación en los primeros años de pertenecer al movimiento chicano, fue la siguiente: ayudaba en lo que podía como organizar eventos poéticos, así como los Simposios de Pensadores del Tercer Mundo y otros más. También ayudaba en sus funciones para recaudar fondos como ventas de pan dulce, tacos etc. Me daba de voluntaria para ayudar a organizaciones como CAMP (College Assistance Migrant Program) entre otras. También tuve en el barrio, en el Washington Neighborhood Center, un programa tutorial en el que llevaba estudiantes de la universidad a enseñar a los niños. Lo óptimo de mi participación fue cuando formulé y comencé a enseñar el curso “La Mujer Chicana” en el Departamento de Estudios Étnicos, de la Universidad Estatal de California en su campus de Sacramento-CSUS. El gran poeta y activista chicano, José Montoya, era catedrático en este mismo departamento. Después de haber recibido algunos reconocimientos por mi participación en el movimiento chicano, mi mayor orgullo llegó un día cuando José Montoya me llamó y me dijo: “Gracias, Graciela, porque nunca nos has dejado”. Este ha sido el mejor reconocimiento que he recibido en mi vida. José tenía razón. He creído siempre que es un derecho de todo ser humano tener acceso a la educación formal. Me uní al Movimiento Chicano Pro-derechos humanos y civiles. Para los chicanos, acceso a una buena educación era lo que más deseaban. Sentí como si un imán me atraía hacia ellos. También a José Montoya siempre le viviré agradecida. El organizaba programas y recitales de poesía en la universidad. Fue él quien me apoyó é invitó a leer mi obra poética en público, por primera vez en mi vida. Cómo recuerdo cuanto sufrí, y las ansias que me causó, pues tenía demasiado miedo de leer en público. Yo había leído en programas escolares pero nunca en programas en público en general. José lo notó y con sus palabras me animó mucho. Al fin, temblaba pero lo hice. La Poesía de Graciela B. Ramírez REBOZO Rebozo que humillado te escondías, mas con la revolución volviste altivo en los hombros de Frida** quien sin miedo te sacó de penumbras ensalzando los colores brillantes de tus hilos. Así volviste a colorear las fiestas adornando con gracia a las mujeres quienes ahora en cuerpos te lucían o zapateando en moños te enredaban. Rebozo que en los campos de batalla de la intemperie protegías a guerrilleras y en las noches cubriendo a los amantes creabas mundo privado en que chasquidos de besos resonaban en el aire y después el amor bajo de ti hacían porque quizá la luz del sol Ya no verían Rebozo, con tus hebras acaricias de las futuras madres sus vientres esponjados, entibiando matrices, dando calor a fetos, enlazando dos seres en comunión sagrada Cordón umbilical de madre y niño porque cuando ellas cargan, cual marsupias, a sus tiernos infantes, ellos saben que no hay peligro alguno porque tú con firmeza los sostienes. Y también con amor cubres los senos cuando el pequeño cual gatito tierno mama la tibia leche de su madre y arrullado con ritmos de latidos sueña envuelto en respiros melodiosos y despierta al sentir hondo suspiro y se ve reflejado en dulces ojos. **Nota Bene: Frida Kahlo volvió a hacer famoso el rebozo de seda mexicano. A este rebozo también se le conoce como Rebozo de seda de Santa María, el pequeño pueblo en el estado de San Luis Potosí, en donde se encuentran los telares de rebozos. Ahí mismo también se pueden ver los sembradíos de las plantas de las que se alimentan las orugas que el público en general conoce como “los gusanos de seda”. Frida también mostró el modo, arte y orgullo de portarlo el rebozo. Fue precisamente durante las décadas de los años sesenta y setenta que las mujeres chicanas, México-americanas y latinas volvieron una vez más a hacer legítimo el uso del rebozo, tanto el de algodón como el de seda. -LC Tlaloc There came a day when your gigantic statue was moved from its birth place to Chapultepec’s sacred emerald forest where hundreds of crickets sing for you the eternal welcoming song Slowly, so slowly 168 tons of stone moved through Tenochtitlan’s streets cradled in the specially-built trailer going slowly, So slowly. During the night, work crews disconnected and reconnected electrical wires needed because of your 23-foot height. Perhaps you laughed At all the attention From the multitudes After the 30-mile journey, came the huge explosion, like a Big Bang, embedding our memories back in our city recalling years of invasions, centuries of deep pain. But finally, the gift of spiritual Renaissance as you passed through the Zócalo, The Great Temple, El Templo Mayor. At that precise instant came the deluge, your fertility water, your life-giving water, your survival water, your baptismal water, your melting jade rain that poured over us running in force through our city washing us in blessings and forgiving waters through archeological sites, the burial homes of your ancestors the burial homes of our ancestors. Tláloc, the Great Tláloc: The eagle and the serpent Acknowledged you As the Lord of the Third Sun, As God of all Water. PINCELADAS Instantly becoming one With the new born moon And the eastern star All of a sudden Autumn smiles Reddish leaves Cosumnes River Witness in silence Courtship of cranes The broom Escapes from my hands Dishes Look at me with anger Only the pencil Calls me by my name Magic of Jazz Is for me Sensuality and Spirituality Interwoven Only the pencil Calls me by my name Rain, flamenco woman Dancer Stamping On the roof of my house. **CHICANOS Y LA LENGUA Esta es la historia de la gente… que nace o emigra en retroceso, a esas tierras que ancestros disfrutaron, a lugares viniendo de regreso, que ejércitos extraños conquistaron, sitio donde las grullas con su beso y su baile, colonias iniciaron. Esta es la gente que con ansia busca, un lugar en el sol, cosa muy justa. ... **EPIFANÍA CHICANA Aztlán renace, del chicano cuna su núcleo de las cuatro direcciones aurículas en Utah y Colorado ventrícula del sur en Arizona y otra en Nuevo México hechicero, Aztlán cuyas arterias cristalinas de estrellas salpicadas son Ríos Grande, Colorado y también el Sacramento. ... **LC: Estrofas de Educación: Una Epica Chicana, p. 3 y 24 GBR: Aquí estamos José Montoya y yo esperando una de las cuatro ceremonias pre-Colombinas en Sacramento (la de los niños, la de las jóvenes o Xilonen, la de los jóvenes y el Día de los Muertos). En los setenta José fue uno de los iniciadores de ellas y tuvo a su cargo el altar del norte o el de los viejitos. Yo empecé en el sagrado círculo como a principio de los ochenta y duré en la dirección del norte con José como 25 años o más que fueron inolvidables pues pasar más de 9 horas en compañía de José preparando el altar, marcar el círculo con polvo de maíz, mantener el fuego en el salmador, esperar al grupo que iba a recibir consejos y dárselos fue una de mis mejores experiencias. Con él y los Chicanos aprendí muchísimo. Generalmente leo con mi grupo “Escritores del Nuevo Sol”. Yo soy la que organizo los recitales poéticos en Sacramento. Nuestros programas son en lugares como “Sol Collective”, “Luna’s Café”, y “The Poetry Center”. Hace tiempo iba con mi grupo de escritores a leer en las ciudades de San Francisco, Stockton, Yuba City y otros lugares en California. También en ocasiones leo como parte del grupo al que también pertenezco “Círculo de Poetas & Writers” con base en Oakland, California y miembros en varias ciudades del norte de California. LC: ¿Cómo y dónde pueden los interesados conseguir el libro Educación: Una Épica Chicana?

1) De la autora: email: [email protected] 2) Sol Collective, Sacramento, California LC: No hay duda, apreciada Graciela, que has tenido una larga y fascinante carrera como catedrática y poeta. Me encanta tu actitud ante la vida: siempre optimista. Eres de gran inspiración a todos nosotros, tanto a los “Escritores del Nuevo Sol” como los miembros del “Círculo de poetas & Writers”. Mil gracias por tu participación en esta serie de entrevistas, patrocinadas por el periódico bilingüe Somos en escrito y por “Círculo de poetas & Writers” en la bahía de San Francisco. **En especial, mis más sinceras gracias a Jenny Irizary of Somos en escrito, por su paciencia y asistencia técnica en esta serie de entrevistas mes tras mes. Abrazos, Jenny. **Igualmente, gracias a Paul Aponte y Betty Sánchez de “Círculo de poetas & Writers” (SFBA) y “Escritores del Nuevo Sol”, Sacramento por su ayuda con las fotos que aquí se incluyen. © Poetry, Graciela Brauer Ramírez, de su libro: Educación: Una Épica Chicana Undesirable – Race and Remembrance is a collection of poems by Robert René Galván, inspired by a boyhood raised in the heart of Texas, days spent between his folks’ home in San Marcos and family in San Antonio. René has a way not only of shaping the meaning of words but how he wants us to see and feel what he has seen and felt: in this book, his memories become ours. Born in San Antonio, he now lives in New York City, a noted Chicano poet and multi-talented musician. He is the product of a legacy fashioned by Galván’s antepasados who survived the Great Depression, the WWII years, the decades of discrimination and deprivation–a communal memory that he treasures and preserves in this book.

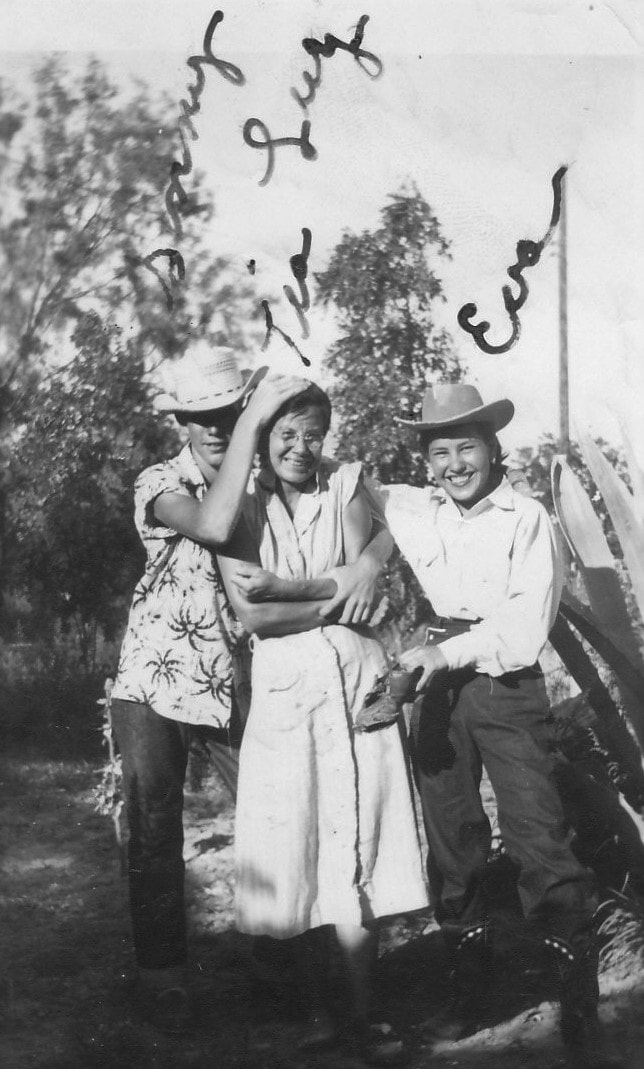

antepasados who survived the Great Depression, the WWII years, the decades of discrimination and deprivation–a communal memory that he treasures and preserves in this book. Galván tells of his elders riding on aging trucks to harvest a few dollars from the fields in the ’30s and ’40s, of his writer father filling his ink pen, its “barrel, incandescent as opal,” of the childhood home bought through a white friend so his family could buy it, even of the relentless reach of racism when recently a white man cursed him for being brown in a NYC supermarket. The subtitle, Race and Remembrance, speaks to the dark undertones of the obras in his book; the cover hints at the seemingly fun trips his elders made from Texas to California to harvest the grapes, pick clean the beet fields, and whatever other crop farmers were hiring workers to pick. The cover photo shows his mother, Eva Mireles Ruiz, third from the left, with some of her siblings and cousins, seated, legs dangling, on the bed of Abuelito Toño's truck, which carried the family to California and back as migrant workers. His Aunt Belia is far left and his Uncle Reyes (of the poem, “Hero”) is on the far right. An earlier collection of poems titled, Meteors, was published by Lux Nova Press (1997). He is also featured in Puro ChicanX Writers of the 21st Century (2020). Another book of poems, The Shadow of Time, is forthcoming from Adelaide Books in 2021. Other poems are found in Adelaide Literary Magazine, Azahares Literary Magazine, Gyroscope, Hawaii Review, Hispanic Culture Review, Newtown Review, Panoply, Somos en Escrito Magazine, Stillwater Review, West Texas Literary Review, the Winter 2018 issue of UU World, and Yellow Medicine Review: A Journal of Indigenous Literature, Art and Thought. Copies are available in print and e-book formats from online booksellers (including Amazon and Barnes & Noble), but we ask that you support your local bookstores.

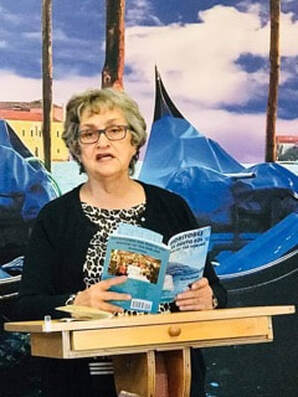

JoAnn Anglin JoAnn Anglin JoAnn Anglin THE POET: IN HER OWN WORDS CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE I think I was just under 3 years old, and already had 2 younger sisters, and we lived in Bremerton, Washington. My Dad was a truck driver. We were all three baby girls in a small, crowded room — it could even have been some kind of back porch, it was very light, sunny. I was standing in my crib, and my dad came in. I recall him looking at us, smiling in delight, as if he was thinking, Look at what I’ve created! All my memories of those early years, up until the time I was around 11 years old, are pretty good. Due to the Second World War, we did some moving around. My dad was drafted into the Navy, so my mom took us back to their home area of South Dakota, where we lived with her parents for a while out in the country. Then my dad was stationed at Treasure Island and we came out here and lived in Hayward for a while. My mom was fine with driving back and forth cross country. Once he shipped out, she moved to Sacramento; we lived in the garage of an old friend of hers who rounded up beds and cribs for us. My dad was probably a bigger influence on me than my mom. Later, some of my first poems would be about him. We had good conversations and he always paid more attention to what was going on in the world. I am a feminist, but always interested to hear the male point of view. I don’t write about those specific locations, but I do realize that I became an observer at an early age, Some might find this now hard to believe, but I was a pretty quiet kid and on the shy side. Usually very obedient. We were strong on rule-following. I can look back at all those years like a slide show, scene after scene, in my head. Going to school was where I became more outgoing. They were Catholic parochial schools from 1st grade through high school. At first, we lived in public housing. In retrospect, it was kind of dumpy, but with a post-war housing shortage, everyone was in the same boat. This was before the days of air conditioning, and the insides were small and crowded, so we all spent a lot of time outside. I walked through Southside Park to get to Holy Angels School, and we played at the park. Before I started school, my mom taught me how to print my name. I was satisfied to spend a lot of time on my own. I wasn’t rebellious, but I was pretty independent. In 3rd Grade, with my dad’s VA-FHA loan they bought a house in a little subdivision, with railroad tracks and empty fields around us. I think the religious sisters who taught in our schools were okay, but favored well-behaved girls. In those days of corporal punishment, even I got my hands whacked with a ruler a few times. But the boys got the worst of it. Even worse, in our school at least, there were often 50 or more kids to a classroom. One thing my sisters and I recall is that there was no sharp demarcation between not-reading and reading. It was just something we flowed into, like a creek into a river. Also, we were strict-practicing Catholics. It’s almost 50 years since I left the church, but I have a great sympathy for writing that includes spiritual aspect, including the idea of mystery. And many of my poems directly or indirectly refer to Catholic terminology or ceremonial practice. About age 10 or 11, I read a lot and loved movies and wanted to make my own stories. Of course I didn’t understand about plot or structure, so the stories might start with a description of a heroine, but then just trail off with no conclusion I loved words for as long as I can remember, and would read everything, breakfast cereal boxes to comic books to Reader’s Digest. I read the newspaper funnies and, before long, some articles and letters to the editor. In high school I wrote some letters to the editor myself. I generally got good grades, but don’t recall creativity being encouraged. The emphasis was on learning the correct answers and responses, especially related to the catechism. But I will always be grateful to Sister Mercy in 7th and 8th grades for giving credit for poetry memorization. We were part of the pre-Boomer generation, my friends and I would create little skits or dances and might perform them at lunch time on rainy days when we had to stay in the classroom. I didn’t know anyone who took piano lessons, although I took tap lessons for a few years. I would add that I was very daydreamy, but that fantasizing didn’t get written down much. During elementary school, drawing was a more usual artistic outlet for me. The topic of fairness was on my mind from an early age. This would come up in my assignments for speech or debate classes. And I always wished to have more beauty in my life. I also saw life as struggle and that often surfaces in my writing. In high school, after turning in some essay assignments, I was recruited to be editor of my school paper. I became deeply involved in all kinds of writing then — interviews, reviews, profiles, etc., and also began to understand about layout and some basics of journalism. This was never seen as a real career prep, though, just an extracurricular activity. POEMS Easter 1999, to my Dad I’m thinking of you and thinking of Mom, And many Easters now long gone; Thinking of eggs and candy rabbits, Of jelly beans and pastel baskets, Of Lenten churches, purple-clad, And Easter pancakes we sometimes had. From out of the house, we’d all of us file And into the old green Plymouth pile. Some of us sang then, in the choir While showing off our new attire – Our shiny shoes and new straw hats – and briefly put aside our spats. I remember those days, and I’m glad we had ‘em; Memories that can still warm and gladden. Now, thinking of flowers and alleluia, Again I wish Happy Easter to you! Neri’s Sculpture: “Nude” (Written sometime in the late ‘90s) She isn’t whole, doesn’t know if she ever will be. Since her shatter, she has started to disappear. Her once-strong edges of sweeping curves, elegant angles demarcated her world. Sometimes she misses what was solid, sometimes not. Unexpected barbs cannot hook her now, nor tear her substance. As the abrupt world flows around her shards of her being chip off. She is amazed at what can pass through. Once somebody’s memory, now a faded dream of essence that uses space, shifts, casts shadows. Exquisite tension holds the stones of her in shapely structure, a cairn. She tries to move in fluid shimmer gatherer of river gravels that lead to dissolve, shuffling rocks that glint and reflect what pours into yet never fills her. Somehow the shaky sculpture keeps moving forward. She is seen as through frosted glass, and knows well the force of her yearning, but not whether she yearns to be whole or to fully dissolve. The Chagall Lovers October 2003 (Written for Arturo and Christina Mantecon) Ascending each evening, they float in the sky drawn up by kisses and each other’s eyes. We hold our breaths, but they are buoyed up above city streets on thermals of love Their bouquets trail petals marking their flight through satin blue evenings of levitation They stair step the roofs in the forest of dusk glisten as moon rise whispers its secrets And gaze past their radiant halo songs to stars chiming softly in heaven’s seas Tender as tulips emerging from earth they hold each other in night sky gardens Up there with fiddlers and gods and devils dancing with goats and calves and doves Nourished on scents from the orange trees below veiled in the rapture of fortunate love Their hands round the necks of roosters and horses, tangled in garlands braided in manes, The town beneath is a chorus of wishes that rise up like bubbles, like scarlet balloons. They smile. They smile at gravity that has nothing to do with them. Secrets of a Babysitter As if she were a robot with no curiosity, They wave themselves away Sure she has homework, they say it’s okay To have some snacks or use the telephone. She bathes the children, reads to them Spoons ice cream into slack pink mouths. Once they are in bed, she eyes drawer pulls And door handles, cupboards and latches She knows where the crème de menthe Sits stickily on the pantry shelf Where the glossy Polaroids are kept In the back of the lingerie drawer While children sleep she fingers coupons Foreign coins and keys in the kitchen drawer Examines paperback books, CDs and videos Turns album pages, sits at the computer Shakes each pill bottle in the medicine cabinet Removes and pockets one from each prescription. Sprays herself with golden scents from a mirrored Tray, slips on a silky camisole that skims her nipples Smacks her lips as she tries on lipstick in shades She’d never wear, wonders at its fruity, slippery taste. The News March 2007 No news is not good news No news means something is in a gather of foreboding, lurks under snarled brush, just beyond the darkened horizon. No news means a smudge on the old photograph, a missed chance to reclaim that patient sepia image. Stains only worsen when rubbed. To fray lacks the order of ravel. There was a song, a vinyl record, a larkish trill of hope rising, now scratched by disregard. Something once held with care set now among danger. Imagination both helps and hurts. News keeps breaking into or out. Patch the shattering — tape or spackle may soften the force, but it comes. Seepage will enter, its outline remain. Boy’s Ranch November 2010 Before you arrive at the gate, you have wound through the clefts of pale yellow hills. You have seen flocks — wild turkeys, then Canada geese — and shallow pools reflecting blue skies. Further, like old men, crouched turkey vultures pause in their pavement feast. Beyond fences: cattle, tilting trees. Drive on through the oak grove where a loping coyote stares back. The gate arm lifts, lets you pass. Not such a bad place, you say at the last curve, as jays and woodpeckers fly through the double rolls of razor wire atop the 20-foot steel fence. My To-Do List April 2013 I checked off the decision to have two failed marriages. And children who lacked confidence in me: checked. The pet dog who ate the poison. Checked. There was the boss who made me cry. Check. The one who made me crazy. Check. Plumbing that corroded, beloved serving dish that broke. Check. Wrong turn that took me out of my way for two years. Check. Many checks for arguments on religion, race, sex, politics. Laughing in the wrong place. Saying Yes, saying No. Saying too much. Not enough. Check, and check. Unfiled income tax. What I owe family, former lovers. All checked off. Sleeping one more time with that man. Not sleeping with another. Saying I’m sorry too often. Double checks. Saying ‘sleeping with’ instead of sex. Saving the money, getting the cheapest substitute. Oh yeah, check. Fearing dogs and horses. Check. Smoking, check. Being persuaded, checked off again. In heavy ink. The days I don’t know who I am. Or why. Checking. Then, checking in too late. Checking out too soon. Source June 2015 Was I, then, in her? That serf girl, many centuries past, who hauled hay. Potato digger who sought small branches in the woods. Who paused to stand, wipe sweat from her brow. Was there ever a wondering of what lay in far castle, or further down the road? Probably an unwilling or unwanted suitor, to plant in her as she planted beans for another crop, wondered how much to raise, how much to keep, or pass on to the owners. And what of her child, or several, wrapped and slung against her soon worn body? And that child’s child? And so on. Where in me is planted the something of her? In how I pause to touch a day lily, to smell a melon, to note the lowering clouds? In how I have birthed children? And now, these poems, planting words in a line for her who could not read. Word of Mouth March 2016 I watch you sleep and lay beside you and want to go where you go, behind your eyelids. At times, you murmur soft indistinguishable sounds, urgent but amused, and I know you are not speaking to me. I try to imagine that language, that realm: if you are in a cabin on the mountain, or on the mountain looking birds in the eye. They would understand you, shy looks and cocked heads. Trust. Your voice resembling chirps, assenting to flight that’s regardless of wings, needs nobody. You start a little. You must be tasting the air, finding the currents, riding the updrafts. I want to be the one you return to. You can always land on me. A Day Muy Frio (date unsure) Como esta? Estoy bien. Oh yeah? Explain, por favor: Where is your sombrero? Your jaqueta? Your dinero? Donde es el carro, to ride to the supermercado? Donde es tu amigo? Captured by la migra? NEWS poem: (January 2020) “Inmates Released into ICE Custody” What do they try to carve when they slice this man away? What shape beautified by loss of his hands and eyes, when he becomes swiped off leftover clutter? Look for the resignation, sour, like rain’s stain already marking his worn surface. Instead of putting away the pain, and anointing what has healed, their hands rip off the new skin, throw it to the desperate dogs.  Escritores del Nuevo Sol anthologies Escritores del Nuevo Sol anthologies PLÁTICA: JoAnn Anglin (JAA) and Lucha Corpi (LC) in Conversation: LC: By circumstance, being an immigrant wife in the Bay Area, having no family here, being the mother of a young child, and years later going through a divorce, I began to write just as an exercise on spiritual and mental survival. I needed to know who I had become after getting married, and coming to the U.S. So many questions I had to find answers to. I felt that putting my feelings and life experience in the U.S. in writing would help me to make sense of my life and survive emotionally. It did. And I discovered I was a poet and writer in the process. You’ve told me the following about your beginnings as a writer: JAA: We had no creative writing classes (in high school), no literary journals. On my own I wrote poems, which I rarely showed, and song lyrics which I never showed. These were mostly imitative of popular music, show tunes, or church hymns. It would take community college to really open my mind and awareness of other creative or philosophical paths. My reading expanded, sometimes via assignments, and sometimes from recommendations from other students. Sometimes at home, I would want to talk about the reading, much as I’d liked to retell the movie stories when younger, but my interests made me the ‘odd duck’ in the family. LC: Was there a mentor/Teacher? Other poets at the time, from whom you learned your craft? JAA: I wish I could say yes. One community college English teacher, Margaret Harrison, saw potential in me. I can see this looking back. She wanted me to apply to Holy Names College in the Bay Area, but I was positive this wasn’t something my family could afford. I knew nothing of scholarships, loans, or work-study. I didn’t see a way. I never saw a counselor. I soon dropped classes so I could work and afford a (junky) car. I even went to the draft office of the Navy, but was discouraged from joining. By age 20, I was married and pregnant. My husband’s story was similar. Later, after divorcing, we both finished college, me graduating with my BA at age 41! LC: You are a member of Escritores del Nuevo Sol group in the Sacramento area. Later you and some of the poets in Escritores also became members of Círculo de Poetas y Escritores in Oakland and the East Bay Area, including Santa Cruz. The late Francisco X. Alarcón was instrumental in establishing both organizations. As a matter of fact, I was invited by Francisco to attend a workshop-meeting of Escritores. I met many of you there. I was very impressed with the group. I am also very impressed with Círculo de Poetas y Escritores members: Could you share how and when you and Francisco X. Alarcón met? JAA: I have to give huge credit to La Raza Galeria Posada, the Latino Art Center in Sacramento. I became aware of their work when I was a public information officer for seven years at the California Arts Council. At the time, I knew vaguely of the Royal Chicano Air Force, the Chicano artists group, and of José Montoya and Esteban Villa. A couple of my co-workers were the artists Juan Carrillo and Loraine Garcia, and also Tere Romo and Josie Talamantez, so my consciousness was really being raised in this area. I began going to public LRGP events, one of them a poetry reading, organized by Galeria board members Art Mantecón and Francisco Alarcón. At the reading, Francisco announced the decision to start a writers’ group, the Taller Literario. The next week I called Tere Romo who became the Galeria director and curator. I asked if I could join, although I’m not Latino. Her answer: of course! Later the name was changed because people were confused by the word Taller when wrongly interpreted as referring to height. As I recall, Francisco and Art came up with the name of Los Escritores del Nuevo Sol, mainly because of Francisco’s fascination with the Aztec calendar. José Montoya stressed to us the need for preserving Latino arts and literature. We met monthly at LRGP, eventually having public poetry readings, usually related to major holidays – Mother’s Day, Day of the Dead, and such. When the Galeria went through some major inner turmoil, we began to meet at members’ homes. I cannot give enough credit and praise to Francisco Alarcón. Whether personally, socially, in poetry, or in politics, he was the most generous, kind, and forgiving person I have ever known. And I still remain in awe of his talent and energy. I believe that he was at times subjected to prejudice due to his accent or to his being gay. If he felt bitter about it, he never turned that bitterness on anyone else. Like others who knew him, I will never stop missing him. When the Crocker Art Museum hosted the Latino art exhibit, Our America, he invited several of our most active Escritores to be part of a project of ekphrastic art – each participant choosing a painting to inspire a piece of poetry. He also drew on his friendship with and knowledge of poets throughout California, particularly the Bay Area, which led to the positive interactions among the two areas. Some, reluctant to let the interaction fade, later founded the Círculo. We continue to be enriched by it. LC: How has (or not) being in the workshop helped you focus on your poetry in a more productive way? JAA: One major thing: my membership in Los Escritores made me realize that my aptitude was for poetry, not fiction. We took turns facilitating exercises at our meetings, and I began to understand better the difference between words spoken and words on the page. Sometimes I’d bring a poem to read, and realize as I read it that segments of it, or just one word, didn’t really work. One of those exercises, by the way, was to give human personality to a non-human object. Francisco’s poem was called “Laughing Tomatoes,” which inspired him to write a series of related poems and became the title of his first children’s book. He also urged us to put together our first anthology of writing by Los Escritores. LC: I love your “My to do list,” poem. Do you remember what you were doing when the muse showed up? What was the first line, the first imagined “when”? JAA: Thank you! Interesting that you refer to the muse. I recently read a writer’s comment that if you wait for the muse, you will never write. However, that poem did come to me more easily than most. I would say that the more you write, the more you will be able to write. In this case, I had made an off-hand jokey remark about something that I’d have to put on my To Do list, and then that the list was pretty long. I followed that train of thought and the poem came together rather quickly, with fewer drafts than usual. Audiences always like it, too. LC: As a published poet, what advice would you give to younger poets who are just beginning to make their poetry known and establish their authorship? JAA: Write a lot and submit a lot. Read your work at open mics. Read what others are writing. Anthologies are wonderful for this. Do not be discouraged by rejection. It may or may not mean your poem needs more work. Often you will realize that your poem wasn’t quite right for one publication, but will be perfect for another. I have heard of poets submitting a particular poem dozens of times before it’s accepted. I had an instructive exchange at a writing conference a few years ago. During a break, somebody next to me at a table heard I was from Sacramento. An editor, she asked me if I knew Indigo Moor. (He later became our poet laureate.) She said, He’s a wonderful writer. She had been a judge in a contest he submitted to. He hadn’t won the contest, but his name had become familiar to several people who would be paying attention next time his poems came across their submissions desk.  SHORT BIO JoAnn Anglin has taught poetry writing in schools, at Shriners’ Children’s Hospital, for a program with Crocker Art Museum, at a senior facility, and most recently, for 8 years at California State Prison, Sacramento (New Folsom). JoAnn received a District Arts Award from the Sacramento City Council and the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors. A coach for 10 years for Poetry Out Loud, she is a member of California Poets in the Schools (CPITS), the Sacramento Poetry Center, the Círculo des Poetas y Escritores, and Los Escritores del Nuevo Sol/Writers of the New Sun. Several journals and anthologies have included her poems, most recently, The Los Angeles Review of Books. LC: Also, are you participating in any programs/readings in the area in the near future? How can people contact you about future programs and presentations? Do you have a newsletter? E-mail? Please tell:

JAA: The pandemic has pretty much stopped everything for now, although I’m encouraged with what people are doing via the ZOOM platform. A local publisher, 3 Bean Press, published my chapbook Heat in late January. I had one reading, and another scheduled, when everything was shut down. My work at the prison is now being done in a remote learning format and I really miss the in-class participation. Once the world evolves into whatever new shape it takes, I’d love to do more readings. My email is: [email protected]. LC: It’s been wonderful getting to know you through our mutual work with the Círculo de Poetas y Escritores, JoAnn. Mil gracias, JoAnn. Hasta pronto. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed