New Poetry by Ivan ArgüellesTHE FALL OF KABUL carpet-baggers locusts cannibals lice the head turns to stone the moon is drawn out of its well and decapitated in a dust flurry minutes before the evacuation promises of paper-flowers fruit without vermin bread ! for two decades a series of statues come and gone artillery composed of offal and headwinds ox-carts bearing sultans of medieval dialects everything a matter of renunciation movies cosmetics opium military footwear the greatest Demon in the world has just surrendered his vices in a big photograph swap history is written on mattresses with bedbugs remember the Soviet carrion ? remember the big Buddha at Bamian ? five thousand years since the Aryans bruited the Vedas in the Hindu Kush and today nothing but a reversal of system and value blond poster-girls peeling off bloodied walls hoodwinked soldier boys from Iowa City haunted by the part they played dismembering the carcass of progressive Reform Jihad ! Mujahideen ! turn the volume up ! the Twin Towers were destroyed by fireflies a nuisance of idioms and heresy monstrous illiteracy of social media lies verbiage and tattooed air multiples of Zero Balkh the birthplace of Rumi surrenders ! President of USA suffers from PTSD a painted screen a flutter of Chinese diplomats wearing poisoned masks an x-ray of Night what good are stealth bombers and drones ? red ants versus black ants ! civilization ! mendacity of General Petraeus and the CIA operatives who drill like moles through earth nothing is solid and even less is holy the Beloved ! houris wearing burkas on Main Street Yea this day is Paradise and Gehenna above and below and forever ! 08-15-21  Ivan Argüelles is a Mexican-American innovative poet whose work moves from early Beat and surrealist-influenced forms to later epic-length poems. He received the Poetry Society of America’s William Carlos Williams Award in 1989 as well as the Before Columbus Foundation’s American Book Award in 2010. In 2013, Argüelles received the Before Columbus Foundation’s Lifetime Achievement Award. For Argüelles the turning point came with his discovery of the poetry of Philip Lamantia. Argüelles writes, “Lamantia’s mad, Beat-tinged American idiom surrealism had a very strong impact on me. Both intellectual and uninhibited, this was the dose for me.” While Argüelles’s early writings were rooted in neo-Beat bohemianism, surrealism, and Chicano culture, in the nineties he developed longer, epic-length forms rooted in Pound’s Cantos and Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. He eventually returned, after the first decade of the new millennium, to shorter, often elegiac works exemplary of Romantic Modernism. Ars Poetica is a sequence of exquisitely-honed short poems that range widely, though many mourn the death of the poet’s celebrated brother, José.

0 Comments

Suburbano Ediciones publishes a bilingual collection of 32 poems by Hyam Plutzik (1911-1962) translated into Spanish by 14 translators, edited by George B. Henson, with a foreword by Richard Blanco.Richard Blanco reads the foreword. Richard Blanco was selected by President Obama as the fifth inaugural poet in U.S. history, the youngest and the first Latino, immigrant, and gay person in this role. Born in Madrid to Cuban exile parents and raised in Miami, he interrogates the American narrative in How to Love a Country. Other memoirs include For All of Us, One Today: An Inaugural Poet’s Journey and The Prince of Los Cocuyos: A Miami Childhood. A Woodrow Wilson Fellow, Blanco serves as Education Ambassador for The Academy of American Poets and as an Associate Professor at Florida International University. Connecticut Autumn I have seen the pageantry of the leaves falling-- Their sere, brown frames descending brakingly, Like old men lying down to rest. I have heard the whisperings of the winds calling-- The young winds—playing with the old men-- Playing with them, as the sun flows west. And I have seen the pomp of this earth naked-- The brown fields standing cold and resolute, Like strong men waiting for the end. Then have come the sudden gusts of winds awaked: The broken pageantry, the leaves upflailed, the trees Tremor-stricken, the giant branches rent. And a shiver runs over the remnants of the brown grass-- And there is cessation.... The processional recurs. I have seen the pageantry. I have seen the haggard leaves falling. One by one falling. Otoño en Connecticut He visto la ceremonia de las hojas cayendo-- Sus secos esqueletos marrones descendiendo quebrados, Como viejos hombres que se acuestan a descansar. He escuchado los susurros de los vientos llamando-- Los jóvenes vientos—jugando con los viejos hombres-- Jugando con ellos mientras el sol va hacia el oeste. Y he visto la pompa de esta tierra desnuda-- Los campos secos, fríos y resueltos, Como si fueran hombres fuertes que esperan el fin. Y entonces llegan sin avisar las ráfagas de viento que despiertan: La ceremonia quebrada, las hojas hacia arriba agitadas, los árboles Estremecidos, las ramas gigantes desgarradas. Y un temblor atraviesa los restos de los pastizales secos-- Y hay un cese.... La procesión se repite. He visto la ceremonia. He visto a las demacradas hojas cayendo. Una por una, cayendo. Traducido por Pablo Brescia Hiroshima The man who gave the signal sleeps well-- So he says. But the man who pulled the toggle sleeps badly-- So we read. And we behind the man who gave the signal-- How do we sleep? And they below the man who pulled the toggle? Well? Hiroshima El hombre que dio la señal duerme bien-- Eso dice, al menos. Pero el hombre que accionó la palanca duerme mal-- Eso leemos. Y nosotros, los que estamos detrás del hombre que dio la señal-- ¿Cómo dormimos? ¿Y los que están debajo del hombre que accionó la palanca? ¿Y? Traducido por Pablo Brescia The Milkman The milkman walks with mysterious movements, Translating will to energy-- To the crunch of his feet on crystalline water-- While the bad angels mutter. A white ghost in an opaque body Passing slowly over the snow, And a telltale fume on the frozen air To spite the princes of terror. One night they will knock on the milkman’s door, Their boots crunch hard on the front-porch floor, One-two, open the door. You are the thief of the secret flame, The forbidden bread, the terrible Name. Return what is let; go back where you came. One, two, the slam of a door. A woman crying: Who is there? And voices mumbling beyond the stair. Is there a fume in the frozen sky To spell that someone has been by, Under the sun and over the snow? El lechero El lechero camina con movimientos misteriosos, Que traducen la voluntad en energía-- Con un crujido de sus pasos sobre el agua cristalina-- Mientras los ángeles malos murmuran. Un fantasma blanco en un cuerpo opaco Que pasa lentamente sobre la nieve Y un vaho delator en el aire helado Para atormentar a los príncipes del terror. Una noche golpearán en la puerta del lechero, En el piso del pórtico anterior, sus botas crujirán duro, Uno, dos, abre la puerta. Eres el ladrón del fuego secreto, El pan prohibido, el Nombre terrible. Devuelve lo prestado, vuelve a dónde viniste. Uno, dos, el golpe de la puerta. Una mujer grita: ¿Quién está ahí? Y voces murmuran más allá de la escalera. ¿Hay un vaho en el cielo helado Para anunciar que alguien ha estado Bajo el sol y sobre la nieve? Traducido por Ximena Gómez y George Franklin On the Photograph of a Man I Never Saw My grandfather’s beard Was blacker than God’s Just after the tablets Were broken in half. My grandfather’s eyes Were sterner than Moses’ Just after the worship Of the calf. O ghost! ghost! You foresaw the days Of the fallen Law In the strange place. Where ten together Lament David, Is the glance softened? Bowed the face? De la fotografía de un hombre que nunca vi La barba de mi abuelo Era más negra que la de Yahvé Justo después de que las tablas Fueron partidas en dos. Los ojos de mi abuelo Eran más severos que los de Moisés Justo después de la adoración Del becerro. ¡Oh fantasma! ¡fantasma! Previste los días De la ley incumplida En la tierra extraña. Donde los diez reunidos Lloran a David, ¿Se enternece la mirada? ¿Se inclina el rostro? Traducido por George B. Henson Coda A recent traveler in Granada, remembering the gaiety that had greeted him on an earlier visit, wondered why the place seemed so sad. The answer came to him at last: “This was a city that had killed its poet.” He was talking, of course, of the great Federico García Lorca, murdered by Franco’s bullies during the Spanish Civil War. But are there not many cities and many places that kill their poets? Places nearer home than Granada and the Albaicín? The poets, true, are humbler than Lorca (for such genius is a seed as rare as a roc’s egg), and the deaths are less brutal, more subtle, more civilized. Against us, luckily, there are no squads on the lookout. There is no conspiracy against us, unless it is a conspiracy of indifference. But there are more powerful things in the modern world (and people who are the slaves of things, and people who are things) that move against poetry like an intractable enemy, all the more horrible because unconscious. They would kill the poet—that is, make him stop writing poetry. We must stay alive, must write then, write as excellently as we can. And if out of our labors and agonies there appears, along with our more moderate triumphs, even one speck of the final distillate, the eternal stuff pure and radiant as a drop of uranium, we are justified. For history, which does not lie, has proven that our product, if understood and used as it ought to be, is more powerful for the conservation of man than any mere material metal can be for his destruction. [This essay originally appeared as the Preface to Plutzik’s collection, Apples from Shinar, published by Wesleyan University Press in 1959 and reprinted in 2011 on the centennial of the poet’s birth.] Coda Un reciente viajero en Granada, al recordar cuánta alegría le había brindado la ciudad durante una visita anterior, se preguntaba por qué lucía el pueblo tan triste esta vez. Por fín se le ocurrió la explicación: “Este es un pueblo que mató a su poeta”. Se refería, por supuesto, al gran Federico García Lorca, asesinado por los verdugos de Franco, durante la Guerra Civil de España. Pero, ¿no son muchas las ciudades y demás sitios que matan a sus poetas? ¿Sitios mucho más cercanos que Granada o el Albaicín? Claro que aquellos poetas son más humildes que Lorca (porque tal genio es una semilla más escasa que el huevo del pájaro rokh), y aquellas muertes menos brutales, más sutiles, más civilizadas. A nosotros, afortunadamente, no nos vienen a perseguir cuadrillas. No hay complots contra nosotros, a no ser el complot de la indiferencia. Pero sí hay cosas más poderosas en el mundo moderno (y gente que son esclavos de las cosas, y gente que son cosas) que asaltan a la poesía como un enemigo inmutable, aún mas horrible por ser inconsciente. Matarían al poeta—es decir, no le permitirían escribir poesía. Nosotros tenemos la obligación de permanecer en vida, de seguir escribiendo, de escribir con toda la excelencia que nos sea posible. Y si nuestros esfuerzos, nuestras agonías, producen—entre los triunfos de mediano valor—aunque sea una migaja del destilado final, esa materia eterna y radiante como una gota de uranio, eso nos justifica. Porque así la historia, que no miente, logra comprobar que nuestro producto, si se comprende y se utiliza como debe ser, puede hacer más para conservar al hombre de lo que podrá hacer cualquier mero material metálico para lograr su destrucción. Traducido por Rhina P. Espaillat (Este ensayo apareció en su origen como prólogo al poemario Apples from Shinar (Manzanas de Sinar), publicado por Wesleyan University Press en 1959 y reeditado en 2011 para conmemorar el centenario del natalicio del poeta.) About the poet / Sobre el poeta: Hyam Plutzik was born in Brooklyn on July 13, 1911, the son of recent immigrants from what is now Belarus. He spoke only Yiddish, Hebrew, and Russian until the age of seven, when he enrolled in grammar school near Southbury, Connecticut, where his parents owned a farm. Plutzik graduated from Trinity College in 1932, where he studied under Professor Odell Shepard. He continued graduate studies at Yale University, becoming one of the first Jewish students there. His poem “The Three” won the Cook Prize at Yale in 1933. After working briefly in Brooklyn, where he wrote features for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Plutzik spent a Thoreauvian year in the Connecticut countryside, writing his long poem, Death at The Purple Rim, which earned him another Cook Prize in 1941, the only student to have won the award twice. During World War II he served in the U.S. Army Air Force throughout the American South and near Norwich, England; experiences that inspired many of his poems. After the war, Plutzik became the first Jewish faculty member at the University of Rochester, serving in the English Department as the John H. Deane Professor of English until his death on January 8, 1962. Plutzik’s poems were published in leading poetry publications and literary journals. He also published three collections during his lifetime: Aspects of Proteus (Harper and Row, 1949); Apples from Shinar (Wesleyan University Press, 1959); and Horatio (Atheneum, 1961), all three of which were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize. To mark the centennial of his birth, Wesleyan University Press published a new edition of Apples from Shinar in 2011. In 2016, Letter from a Young Poet (The Watkinson Library at Trinity College/Books & Books Press) was released, disclosing a young Jewish American man’s spiritual and literary odyssey through rural Connecticut and urban Brooklyn during the turbulent 1930s. In a finely wrought first-person narrative, young Plutzik tells his mentor, Odell Shepard what it means for a poet to live an authentic life in the modern world. The 72-page work was discovered in the Watkinson Library’s archives among the papers of Pulitzer Prize-winning scholar, Professor Odell Shepard, Plutzik’s collegiate mentor in the 1930s. It was featured in a 2011 exhibition at Trinity commemorating the Plutzik centenary. For further information, visit hyamplutzikpoetry.com. Hyam Plutzik nació en Brooklyn el 13 de julio de 1911, hijo de inmigrantes recién llegados de lo que ahora es Bielorrusia. Habló solo el yídish, el hebreo y el ruso hasta la edad de siete años, cuando se matriculó en la escuela primaria cerca de Southbury, Connecticut, donde sus padres tenían una granja. Plutzik se graduó en Trinity College en 1932. Continuó sus estudios de posgrado en la Universidad de Yale, llegando a ser en uno de los primeros estudiantes judíos allí. Su poema “The Three” ganó el Premio Cook en Yale en 1933. Tras haber trabajado un breve período en Brooklyn, Plutzik pasó un año thoreauviano en la campiña de Connecticut, escribiendo el poema Death at The Purple Rim, que le valió otro premio Cook en 1941. Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial sirvió en la Fuerzas Aéreas del Ejército de los Estados Unidos en el Sur Estadounidense y en Norwich, Inglaterra; experiencias que servirían como inspiración para muchos de sus poemas. Después de la guerra, Plutzik se convirtió en el primer miembro del cuerpo docente judío en la Universidad de Rochester, donde ocupó la Cátedra John H. Deane en la Facultad de Inglés hasta su muerte el 8 de enero de 1962. Los poemas de Plutzik fueron publicados en destacadas revistas literarias y antologías oéticas. También publicó tres colecciones durante su vida: Aspects of Proteus (Harper y Row, 1949); Apples from Shinar (Wesleyan University Press, 1959); y Horatio (Atheneum, 1961), el cual lo convirtió en finalista del Premio Pulitzer de Poesía ese año. Para conmemorar el centenario de su nacimiento, Wesleyan University Press editó una nueva edición de Apples from Shinar en 2011. En 2016, se lanzó Letter from a Young Poet (The Watkinson Library at Trinity College/Books & Books Press) que revelaba la odisea espiritual y literaria de un joven judío estadounidense por el Connecticut rural y la Brooklyn urbana durante los turbulentos años treinta. En una narración de primera persona finamente forjada, el joven Plutzik le dice a su mentor, Odell Shepard, lo que significa para un poeta vivir una vida auténtica en el mundo moderno. La obra fue descubierta en los archivos de la Biblioteca Watkinson entre los papeles del profesor Odell Shepard, ganador del premio Pulitzer y mentor universitario de Plutzik, y tuvo un papel destacado en una exposición que conmemoró en 2011 el Centenario del poeta. Para mayor información, visite hyamplutzikpoetry.com. About the translators / Sobre los traductores: Pablo Brescia was born in Buenos Aires and has lived in the United States since 1986. He has published three books of short stories: La derrota de lo real/The Defeat of the Real (USA/Mexico, 2017), Fuera de Lugar/Out of Place (Peru, 2012/Mexico, 2013) and La apariencia de las cosas/The Appearance of Things (México, 1997), and a book of hybrid texts No hay tiempo para la poesía/NoTime for Poetry. He teaches Latin American Literature at the University of South Florida. Pablo Brescia nació en Buenos Aires y reside en Estados Unidos desde 1986. Publicó los libros de cuentos La derrota de lo real (USA/México, 2017), Fuera de lugar (Lima, 2012; México 2013) y La apariencia de las cosas (México, 1997). También, con el seudónimo de Harry Bimer, dio a conocer los textos híbridos de No hay tiempo para la poesía (Buenos Aires, 2011). Es crítico literario y profesor en la Universidad del Sur de la Florida (Tampa). Ximena Gómez, a Colombian poet, translator and psychologist, lives in Miami. She has published: Habitación con moscas (Ediciones Torremozas, Madrid 2016), Último día / Last Day, a bilingual poetry book (Katakana Editores 2019). She is the translator of George Franklin’s bilingual poetry book, Among the Ruins / Entre las ruinas (Katakana Editores, Miami 2018). She was a finalist in “The Best of the Net” award and the runner up for the 2019 Gulf Stream poetry contest. Ximena Gómez, colombiana, poeta, traductora y psicóloga vive en Miami. Ha publicado: Habitación con moscas (Ediciones Torremozas, Madrid 2016), Último día / Last Day, poemario bilingüe (Katakana Editores 2019). Es traductora del poemario bilingüe de George Franklin Among the Ruins / Entre las ruinas (Katakana Editores, Miami 2018). Fue finalista al concurso “The Best of the Net” y obtuvo el segundo lugar en el 2019, en el concurso anual de Gulf Stream. George Franklin is the author of Traveling for No Good Reason (Sheila-Na-Gig Editions 2018); a bilingual collection, Among the Ruins / Entre las ruinas (Katakana Editores); and a broadside “Shreveport” (Broadsided Press). He is the winner of the 2020 Stephen A. DiBiase Poetry Prize. He practices law in Miami, teaches poetry workshops in Florida state prisons, and is the co-translator, along with the author, of Ximena Gómez’s Último día / Last Day. George Franklin es el autor de Traveling for No Good Reason (Sheila-Na-Gig Editions 2018), del poemario bilingüe, Among the Ruins / Entre las ruinas (Katakana Editores), un volante “Shreveport” (Broadsided Press), y es el ganador del primer Premio de Poesía Stephen A. DiBiase 2020. Ejerce la abogacía en Miami, imparte talleres de poesía en las prisiones del estado de Florida, y es el co-traductor, junto con la autora, del poemario de Ximena Gómez Último día / Last Day George B. Henson is a literary translator and assistant professor of Spanish Translation at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. His translations include works by some of Latin America’s most important literary figures, including Cervantes Prize laureates Elena Poniatowska and Sergio Pitol, as well as works by Andrés Neuman, Miguel Barnet, Juan Villoro, Leonardo Padura, Alberto Chimal, and Carlos Pintado. Writing in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Ignacio Sánchez Prado called him “one of the most important literary translators at work in the United States today.” In addition to his work as translator and academic, he serves as a contributing editor for World Literature Today and Latin American Literature Today. George B. Henson es un traductor literario y profesor de traducción en el Middlebury Institute of International Studies en Monterey. Sus traducciones incluyen obras de algunas de las figuras literarias más destacadas de América Latina, entre ellas las galardonadas con el Premio Cervantes Elena Poniatowska y Sergio Pitol, así como las obras de Andrés Neuman, Miguel Barnet, Juan Villoro, Leonardo Padura, Alberto Chimal y Carlos Pintado. Escribiendo en la Los Angeles Review of Books, Ignacio Sánchez Prado lo calificó como “uno de los más importantes traductores literarios en ejercicio en los Estados Unidos hoy en día”. Además de su labor como traductor y académico, es editor colaborador para las revistas World Literature Today y Latin American Literature Today. Rhina P. Espaillat is a Dominican-born bilingual poet, essayist, short story writer, translator, and former English teacher in New York City’s public high schools. She has published twelve books, five chapbooks, and a monograph on translation. She has earned numerous national and international awards, and is a founding member of the Fresh Meadows Poets of NYC and the Powow River Poets of Newburyport, MA. Her most recent works are three poetry collections: And After All, The Field, and Brief Accident of Light: A Day in Newburyport, co-authored with Alfred Nicol.

Rhina P. Espaillat, dominicana de nacimiento y bilingüe, es poeta, ensayista, cuentista y traductora, y fue por varios años maestra de inglés en las escuelas públicas secundarias de New York. Ha publicado doce libros, cinco libros de cordel, y una monografía sobre la traducción. Ha ganado varios premios nacionales e internacionales, y fue fundadora del grupo Fresh Meadows Poets en NYC y el grupo Powow River Poets en Newburyport. Sus obras más recientes son tres poemarios: And After All, The Field, y una collaboración con el poeta Alfred Nicol, Brief Accident of Light: A Day in Newburyport. Rezo a TonantzinBy Rafael Jesús González Tonantzin madre de todo lo que de ti vive, es, habita, mora, está; Madre de todos los dioses las diosas madre de todos nosotros, la nube y el mar la arena y el monte el musgo y el árbol el ácaro y la ballena. Derramando flores haz de mi manto un recuerdo que jamás olvidemos que tú eres único paraíso de nuestro vivir. Bendita eres, cuna de la vida, fosa de la muerte, fuente del deleite, piedra del sufrir. concédenos, madre, justicia, concédenos, madre, la paz. Prayer to TonantzinBy Rafael Jesús González Tonantzin mother of all that of you lives, be, dwells, inhabits, is; Mother of all the gods the goddesses Mother of us all, the cloud & the sea the sand & the mountain the moss & the tree the mite & the whale. Spilling flowers make of my cloak a reminder that we never forget that you are the only paradise of our living. Blessed are you, cradle of life, grave of death, fount of delight, rock of pain. Grant us, mother, justice, grant us, mother, peace.  Rafael Jesús González is an international activist for human rights and social justice, a bilingual poet and writer, Poet Laureate of Berkeley, California, and, always with our deepest appreciation, a frequent contributor to Somos en escrito. © Rafael Jesús González 2020. Poems by Carlota Caulfield from her book Los juguetes de Bertrand / Bertrand’s ToysReconocimiento Hacía bocetos. Aquí y allá una palabra. Después todo fue simple, un fuego interior que lo consumió de golpe. Al poco tiempo, un exilio impuesto. Después un cambio de fotografías y un borrón en la fecha de nacimiento. Bordes geográficos desvaneciéndose y confundidos en garabatos infantiles, y voces, voces infinitas en asedio. Esperas. Reconstruyes tu perfil y tu acento, vuelves a entrar en tu pasado, permaneces en uno de sus rincones, recorres los barrios de sus excesos, y nunca eres un huésped inoportuno, eso nunca te lo perdonarías. Recognition He made sketches. Here and there a word. Later on it was all-simple: an inner fire gobbled him up. A little later, an imposed exile, Later on, different photographs and a blotch over his birthdate. Geographic lines faded and interchanged over infantile scribbles, and voices, infinite voices laying siege. You wait. You redesign your profile and your accent, you reach the past, you settle into one of its corners, you stroll the neighborhood of your excesses, and you're not an inopportune guest, you'd never forgive yourself that. El oratorio de Aurelia La primera mirada es una mano en movimiento. Una gaveta se abre, otra se cierra, y así combinaciones imposibles del cuerpo. Un trapecio de lo familiar, del perchero y la colcha de la abuela. Cortinas donde se esconde la niñez, esas cortinas rojas del teatro, y el show del circo imaginario para mayores de ocho años. Sabiduría del acróbata y del pintor en su gotear de rojos y esos verdes y esos amarillos. Casi se pueden tocar. Entonces, los waltzes pirotécnicos, los abrigos y vestidos con vida propia, la música de acordeón, tangojazz, y trombón, eso parece. Y cuando todo se ha vuelto un Magritte, el timbre de un móvil desata una pelea violenta entre los otros, audiencia de marionetas crueles. Fin de la primera parte. Aurelia's Oratorio At first glance, it's a hand in motion. A drawer opens, another closes, and thereby impossible body combinations. A trapeze of the familiar, of the hanger and Grandma's bedspread. Curtains where childhood hides, those red curtains of the theater, and the show of the imaginary circus for those over eight. Wisdom of the acrobat and the painter in his splashing of reds and those greens and those yellows. You can almost touch them. Then the pyrotechnic waltzes, the coats and dresses coming to life, accordion music, tangojazz and trombone, that's what it's like. And when everything has turned into a Magritte, the ring of a cellphone unleashes a violent fight among the others, audience of cruel marionettes. End of part one. The poem “Aurélia’s Oratorio” alludes to the theater piece of the same name, a combination of a magic surreal show and acrobatics created and directed by Victoria Thierrée Chaplin that her daughter Aurélia Thierrée performs with extraordinary mastery and grace in theaters around the world. Nueve poemas para Charlotte 1. Agrietadas de pasión, las manos del titiritero descansan. Sólo en un pestañear, las marionetas se mueven y se confunden, y se enredan en sus cuerdas. Conmoción de un instante. 2. Dentro del armario, la sombra de un antiguo Pinocchio es una marca perenne. Así se hace la memoria y eso es lo mejor de todo, dejar que el corazón se fragmente con el tacto. Lo inexistente ha dejado un recuento. 3. Sus labios en una taza de té. Un sabor verde de Himalayas se confunde con la vasija terracota curtida por el uso. Capas y capas de residuos, testigos impregnados en el barro. Pone a un lado su diario. Mapa Mundi. 4. Su nombre reaparece en diferentes formas. En caligrafía es trazo llamado Tao. Su efímera inscripción lleva la espiritualidad de los sentidos. Digo y cuento, aunque raras veces es también toque de inscripción propia. 5. Puertas hinchadas de aguas a destiempo, como si la torrencial lluvia se hubiese vuelto un dulce y pegajozo delirio mientras observas las vestiduras extraviadas de la madera. En la ventana, una silente figura vacila. Y de pronto, el espacio de sonidos se confunde con grises, blancos y verdes. Lo de afuera entra y roza tus manos. 6. Ella, la que eres tú en ciertos días, deja un rastro de bruma y se reclina sobre varios senderos. Atrapar lo inasible se vuelve aquí furor y apatía. 7. Pasas bordeando voces. No quieres quedarte en la orilla de la muerte. Como un animal ebrio de miedo te enroscas hasta que la lluvia cese. Palabras en desorden. Trabalenguas. 8. Tú misma eres una abstracción. Todos los remedios disolviéndose. Noches de insomnio cercanas a la locura. Así tu cuerpo. Las treguas conjuradas. La parálisis un abismo de telas. La corrugada pesantez de tu espalda mancillada por bloques terapeúticos. 9. Mientras intocable hasta en la palabra, la presión de dedos y el aire denso de lugar a lugar, a tus labios coarteados les frotas unas gotas de miel y los pules como si fueran un desgarrón purpúreo. Así tus huesos, nervaduras de sombras chinescas lanzadas al piso. Tú. Nine Poems for Charlotte 1. Cracked by passion, the puppeteer’s hands rest. With only a blink, the marionettes move and are baffled, and get tangled in their cords. The commotion of an instant. 2. Inside the wardrobe, the shadow of an ancient Pinocchio is a perennial imprint. This is how memory is made and that’s the best of it all, to allow the heart into pieces if touched. The non-existent has left a trace. 3. Her lips sipping a cup of tea. A Himalayas’ green flavor is fused with the terracotta cup stained by use. Residual layers and layers, witnesses impregnated in the clay. She puts aside her diary. Mapa Mundi. 4. Her name reappears in different ways. In calligraphy it’s a pen stroke called Tao. Its ephemeral inscription carries the spirituality of the senses. I say and tell, although rarely it’s also a touch of self-inscription. 5. Doors swollen by untimely waters, as if the torrential rain had become a sweet and clinging frenzy while you observes the lost garments of the wood. In the window, a silent figure hesitates. And suddenly, the space of sounds blends with grays, whites and greens. The outside comes in and grazes your hands. 6. She, the one you are on certain days, leaves a trace of mist and bends, over several paths. Here to grasp the unreachable is fury and apathy. 7. You stroll around voices. Not wanting to remain on the verge of death. Like an animal drunk with fear you huddle until the rain stops. Words in disorder. Tongue Twisters. 8. You are yourself an abstraction. All solutions are dissolving. Nights of insomnia close to madness. So is your body. Conjured ceasefires. Paralysis, an abyss of cloths. The corrugated and heaviness of your back sullied by therapeutic blocks. 9. While untouchable even by words, the pressure of fingers and the misty air from place to place, onto your cracked lips you rub some drops of honey and you polish them like a purplish tear. And your bones, too, Chinese shadows nervures tossed on the floor. You. Bosques de Bélgica Voz suelta. Pura respiración. Labios de breves heridas. Después, un tañido. Boca sobre el metal. Voz hueca y los labios un pico abierto de pájaro. El aire es murmullos, rumores, silbidos, y marca permanente en la cámara interio. Rapidez del movimiento de la vara, privilegio de una mano. La mano tiene forma de U. Es una U. En el cielo de Berkeley hay pocas nubes, decías lentamente. Cierto, el aerófono es latón ligero, tríptico en un cuadro donde un trombón de vara parece pájaro en vuelo y alas de ángel. ¿Quién recuerda el nombre del cuadro? ¿Cómo se llamaba el pintor? Belgian Forests Voice unleashed. Pure breathing. Lips of brief wounds. Then, a note. Mouth to metal. Hollow voice and lips a bird's open beak. The air murmurs, whispers, whistles, and permanently marks the inner chamber. Rapidity of the valve's movement privilege of a hand. The hand is U shaped. It’s a U. In the Berkeley sky, here are few clouds, you were saying slowly. True, the aerophone is a light brass triptych in a painting where a valved trombone looks like a bird in flight, and angel wings. Who remembers what the painting is called? What was the painter's name?  Photo by David Summer at the Mersey in Liverpool, UK Photo by David Summer at the Mersey in Liverpool, UK Carlota Caulfield is a Cuban-born American poet, writer, translator and literary critic. She has published extensively in English and Spanish in the United States, Latin America and Europe. Her most recent poetry books are Cuaderno Neumeister / The Neumeister Notebook (2016) and Los juguetes de Bertrand / Bertrand’s Toys (2019). She is the recipient of several awards, among them The International Poetry Prize Dulce María Loynaz and The Ultimo Novecento, Poets of the World. Caulfield has also published widely on Argentine poet Alejandra Pizarnik, as well as on other Latin American and Latinx poets, including Magali Alabau and Juana Rosa Pita. She is the co-editor of A Companion to US Latino Literatures (2012 &2014) and Barcelona, Visual Culture, Space & Power (2012 & 2014). She is Professor of Spanish and Spanish American Studies at Mills College, Oakland, California. Mary G. Berg, a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center at Brandeis University, Boston, Massachusetts, has translated poetry by Juan Ramón Jiménez, Clara Roderos, Marjorie Agosín and Carlota Caulfield and novels by Martha Rivera (I’ve Forgotten Your Name), Laura Riesco (Ximena at the Crossroads), Libertad Demitropulos (River of Sorrows). Her most recent translations are of collections of stories by Olga Orozco and Laidi Fernández de Juan.

Dos Poemas del Destino |

| (sobre motivos de George Orwell) |

De niños, junto a un faro, nos creíamos

que ante la oscuridad y las tormentas

los barcos precisaban de la luz.

Hoy sabemos que éramos nosotros

los que más se ayudaban de esa creencia.

Tal vez sea mejor

que todo siga su cauce:

dejar de imaginar, de escribir,

dejar que, incluso en contra suya,

todo siga su cauce.

2.

En ocasiones nada es la mejor solución:

comprobar, sin más, que los días

se engarzan a una arena infalible,

que denigrados los libros

desertan de los estantes,

que prematuramente los cuerpos

se avienen a la ceniza

—los ojos, al vacío—,

que no sirve ya la pregunta

de cuál es o cuál podría ser…,

ni tampoco la respuesta

de que en ocasiones nada

—este poema incluido--

sea la mejor solución.

| Todo el poder que iría adquiriendo la casta de funcionarios (…) lo iría perdiendo el pueblo. José Martí, sobre La futura esclavitud |

nos hace imparciales:

creernos imparciales

nos lleva a la parcialidad.

«Oíd, amigos, la revolución ha fracasado.

Subid las campanas de nuevo al campanario,

devolvedle la sotana al cura y al capataz el látigo»,

escribió León Felipe hace décadas sin incluir

el siguiente reverso tan familiar:

Camaradas, oíd: La revolución ha triunfado.

Subid el nuevo (es un decir) pendón al campanario,

y sin dejar de aplaudir a los torcidos

funcionarios de turno, vedlos cómo se invisten

con la sotana del cura y el látigo del capataz.

New Poems by Ivan Argüelles

antes de abrir la demencia para descubrir

palabra tras palabra que no tiene sentido

diccionario de pulmones ! pulgas y rascacielos !

para mejor comprender lo que pasa dentro del ladrillo rojo

al margen de la calle que nos lleva al sur donde

los muertos tratan de olvidar lo que pasó ayer

cuando la gran máquina de nubes y sonidos

se acostó al lado del mar que sufre tantas camas

inexplicables y sin eco y ahora dime que quieres

con tus ojos apagados y tu mente como sirena

de ulises llamando a todos los náufragos

que la ambulancia está lista a partir !

ya me voy hacia la mejor tortillera que hay

para besarla en su coma de vidas paralelas

y entonces con una tristeza mundial

seguiré caminando un brazo mas famoso que el otro

una oreja de piedra y otra en ninguna parte

para qué poner en dos el uno ?

multiplicar significa morir !

07-21-20

for Joe who appeared yesterday morning

for a fraction of an instant in the doorway

standing in the light of the morning sun

confused with radiance and dazzling

the stanzas of an unwritten poem shift

in the monumental distances of air

crane-feathered shafts rotate like minds

ablaze in the pyramidal distances of sky

stone built on stone stepping to heaven

solar flares like tongues speaking loud

the destructions of cloud and thunder

and ever deeper the effects of amnesia

rain drowning cities of fine dust citadels

of bone and tumult havoc of wheels

spun out of control bringing down all

ten directions and mountains reared

overnight to mark off the western margin

where the archaic sea darkens rushing

to mirror itself in a dream of feathers

and the twins up and down they go

tracing each periphery of rock and grass

measuring how far it is to the lunar aleph

fading like dissolved aspirin at dawn

what fills the ear at such an early hour

if not the Sanskrit parrot reciting

chronologies and adamantine dynasties

names none can rightly recall inscribed

on the reverse of coins or obliterated

by a mere thumb on porous sandstone

libraries ! the tomb of words and to speak

the labyrinthine dialects communing

with deities of the Unseen and Unheard

pages torn at random from the codex

depicting the origins of divine Chaos

night ! splendors of ink in canyons

where the dead revive use of their hands

such a morning atop the great Teocalli

converting sums of air into breathless voice

hail all the heights and renown of fire !

we have come down the Panamerican

visiting each of the summers of 1953

and talking backwards to mummified

relatives wrapped in serapes of liquid gold

we will never reach tomorrow for sure

the Nymph death will take one of us

before the prophesy can be fulfilled

every day is this single bright moment

standing like phantom pharaohs immobile

in the pellucid movie film of memory

you are me and I am you ! there is grass

and maps strewn all over the lawn

and avenues that stretch as far back as

the first city carved out of the womb

ten minutes apart the matching Teocallis

that cast no shadow only black light !

06-11-20

cronología del aire ! arquitectura de las nubes !

soy de poco valor

que lástima ! las abejas en sus columnas verticales

de azul incendiado chupando chupando los huesos

de la hierba dormida

soy azteca

soy caldeo

soy de mucho valor

sierras de sueño blanco que veo nomás

cuando estoy nadando en mi césped de memorias

todo verde desde el hombro izquierdo de césar vallejo

hasta la rodilla derecha de garcía lorca

acumulando los dos las muchas muertes de la luz

aunque vivimos como momias en Tenochtitlan

apenas sufriendo el tránsito de los motores de las plumas

yo lo único que soy es la luna

chafada y transparente como aspirina a mediodía

y hay mares invisibles que suben los pirámides de la frontera

pistolas con ojos !

ahi viene la bala !

dame mi caballo corrompido

yo soy peruano

el último dios soy

el mero dios de la basura hieroglífica de chapultepec

fumando como nunca las chispas baratas

de las olas que han venido a ahogar el estado de california

poco a poco y a menudo con sus pronombres

y hierro de lenguas mas muertas que el sol negro

tapadera y tumba del fuego silencioso

de mis pasos en el jardín unitario de la duda

y por eso digo

yo soy

06-17-20

¿Y si no fuese a volver?

Por Ana Deniz Sutton-Ventura

también fuñía y fuñía

en los siguientes

meses, sin parar un día.

¿Qué dice? ¿Qué idioma es ese?

¿Será italiano? ¿Qué es?

¿Es que así hablan los gatos?

Saltaba en el charco; saltaba en diciembre.

Brincaba en noviembre y octubre. Brincaba por meses.

Con los ojos hurtados de un gato, los zapatos rojos.

La mochila pequeña, el abrigo corto.

¡Qué sonrisa! ¿corría?

Lloraba; reía. Apenas hablando aquel idioma tosco.

Mirando siempre a cada lado de la calle

Con sus ojitos de gato.

¿Cuándo fue que creciste tanto?

¿Dónde está el bebé con los ojos de gato?

¿Se habrá ido?

No lo veo más a diario.

Es que espero que esté bien; hablando más de espacio.

Observando al mundo con sus ojos de gato.

Art and Literature blog: https://caribeixa.blogspot.com/

PREÁMBULO: EN SUS PROPIAS PALABRAS:

Niñez y Juventud de Zheyla Loor Villaquirán

Nací en Portete, un pueblito ecuatoriano aislado y al cual sólo se llegaba en barco, Mi padre me registró a los 6 meses que viajó a la ciudad, el 20 de febrero de 1949. Creo que no quiso pagar la multa, así que todos mis documentos tienen esa fecha. Pero yo festejo el verdadero día en que nací: el 16 de agosto de 1948.

Creo yo tendría 6 años cuando mamá dejó Portete, donde nacimos todos, con sus dos últimos hijos, mi hermano Manolo y yo, para vivir en la ciudad de Esmeraldas. Jamás volvimos, aunque siempre teníamos las maletas listas porque mamá decía que nos iba a mandar de vacaciones con una hermana mayor que vivía allí. A la ciudad sólo se llegaba por medio de un barco muy primitivo. El dolor de la muerte de un hermano de 16 años y por la causa que ya se nos la iba llevando el mar (literalmente porque mi hermano y yo pescábamos desde la cocina), mi mamá decidió abandonar el pueblo. Portete, sigue siendo un pueblito, pero al frente se ha construido un resort muy moderno. Con la marea baja se puede cruzar a pie del hotel al pueblito. Al subir el mar hay que usar una lancha.

Que yo recuerde, estaría yo en 4to o 5to grado cuando comencé a escribir poesía. Casi todas mis compañeras de la escuela primaria eran mayores que yo y tenían enamorados. Supongo que sabrían que yo escribía poemas, por eso me pedían que les escribiera acrósticos para sus enamorados.

No recuerdo los poemas. El único poema que la memoria recuerda es el de mi primer amor por un torero imaginario que conocí en la “plaza”. Con decirte que yo no tenía ni idea de lo que era amor ni tampoco de lo que era una “plaza de toros”. La única plaza que yo conocía era la que también llamábamos mercado. Así es que a mi toreador “lo conocí” en el mercado. Mi maestra no creyó que yo hubiera escrito ese poema, pero lo corrigió y recuerdo la palabra “contendor” supongo de “contender” que ella substituyó por la mía:

Pasando yo por la plaza

vi a un hermoso torero

que por mí daba la vida

que por mí daba su amor

Estamos ya cara a cara

vamos para mi casa

que tengo todo arreglado

para realizar nuestra boda

Aquel torero garboso

le tocó pelear con un toro

de los más feroces que había

El toro ya lo vencía

cuando alzó la vista hacia mí

y dijo: ¡oh morena!

¿aquí habéis estado?

Sí, aquí me hallo mirando,

Mirando cómo peleas

por vencer a tu contendor

Pero, ¿de qué me vale ese honor?

Y así terminó mi vida

con aquel torero

que por mí daba su vida

que por mí daba su honor.

Mis hermanos mayores ya vivían por su cuenta y las mujeres ya casadas, pero todavía había dos hermanas que estaban en un internado estudiando en la ciudad. Allí nos fuimos Manolo y yo. Ya estábamos en edad escolar y por primera vez nos separaron. Me pasé todo el año llorando y por eso perdí mi primer grado. Mi escuela quedaba al frente de la de mi hermano, pero no estábamos juntos.

Mi escuela primaria era monolingüe. En la secundaria teníamos un profesor que había aprendido inglés por sí mismo, así que nos enseñó “a traducir”, entre comillas porque en realidad era puro vocabulario lo que nos enseñaba.

Cuando me casé, mi esposo decidió que debíamos visitar Portete. Tendría 23 años. En aquel tiempo sólo se podía ir en barco. Recientemente se construyó una carretera y dos sobrinos me han llevado las últimas veces que he ido a Ecuador.

Emigré porque estaba casada con “un gringo” que pertenecía al Cuerpo de Paz, “Peace Corps”. Lo conocí en el 2do año de universidad, cuando mi profesor de inglés tuvo que viajar a los EE.UU. y buscaba un remplazo por un mes. Encontró al que iba a ser mi esposo en la calle y él aceptó substituirlo. Así lo conocí. Mi hermano y yo nos sentábamos juntos en la clase de inglés y le hacíamos bromas de su pronunciación en español.

Todavía en Ecuador, nos casamos, y construimos una casa. Estudiábamos francés en la Alianza Francesa porque yo quería continuar mis estudios en la Sorbona. Mi profesor de francés, que también era el cónsul de Francia, me había seleccionado para que yo fuera la segunda estudiante de la Alianza que él mandaría. Mi profesora de literatura de la universidad había sido la primera becaria.

Pero tuvimos un terremoto muy fuerte que hizo que el edificio donde teníamos clases se derrumbara. Como mi esposo pertenecía al Cuerpo de Paz y por estar casado conmigo ya le habían renovado dos veces su estadía, le dijeron que tendría que regresar a los EE.UU. Teníamos los dos 30 años entonces.

Con el derrumbe del edificio terminó el sueño de ir a Francia. Y aquí estamos, en California.

ENTREVISTA:

EN PLATICA: Lucha Corpi (LC) y Zheyla Henriksen (ZH)

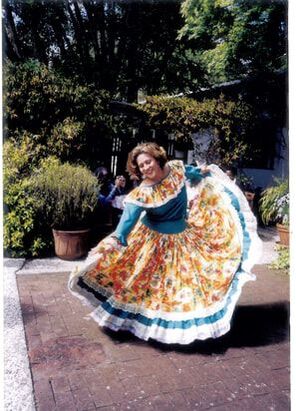

LC: Zheyla, tuve la suerte, por primera vez, de oírte declamar tus poemas en público durante un recital de poesía en Sacramento, California, patrocinado por Escritores del Nuevo Sol en conjunto con Círculo de Poetas. Dijiste algo muy interesante a modo de preámbulo a tu presentación, y es que casi exclusivamente escribes “poesía erótica”.

En general, cuando alguien, y en especial una mujer dice eso, creo que el público inmediatamente piensa en el sexo o acto sexual mismo. Aunque ya no tan a menudo, también consideran a la mujer amoral. No piensan en la sensualidad, la cual es producto de la imaginación. Es decir que el erotismo no es producto del cuerpo, enteramente, y puede no preceder o ser parte del acto sexual. Así mismo, consideran a los poetas (sexo masculino) como primordiales exponentes de la poesía erótica. Aquí mis preguntas con la idea de aproximarnos a tu propia definición de tu arte poético:

LC: A tu parecer, ¿Cuáles son los elementos primordiales que definen la poesía erótica en general? ¿Y de qué manera se manifiestan estos en tu propia obra?

ZH: Bueno, mira, no es que yo escriba exclusivamente poesía erótica, pero me inclino bastante a ella. Lo que pasa es que por haber quedado como finalista en el concurso internacional de poesía erótica en las dos veces que participé, me han dado ese título y yo me lo he apoderado. En cuanto a lo erótico como campo masculino, no lo veo desde la visión histórica sino desde el punto mítico-religioso.

Me explico: Míticamente los ritos “orgásmicos” primordiales le corresponden a la mujer porque es ella la suprema dadora del placer.

Entre muchos estudios, voy a mencionar sólo tres: The Great Cosmic Mother: Rediscovering the Religion of the Earth de Monica Sjöö y Barbara Mor, y en Sacred Pleasure de Riane Eisler, explican que fisiológicamente es en la mujer donde, exclusivamente, existe una conexión similar al trance religioso en el cerebro frontal y el cerebellum lo que permite el enganche al “neocortex”. Por eso en el acto sexual, la mujer experimenta un cierto trance espiritual, el éxtasis. Si observas tú la estatua de Bernini, El éxtasis de Santa Teresa, la contorsión y el relajamiento del cuerpo de la estatua es similar gesto del éxtasis sexual, (tuve la dicha de verla en W. D.C.)

LC: De acuerdo. Entonces en todo esto, la mujer es la dadora del placer en la pareja! Y si es así, ¿Qué papel juega el hombre?

ZH: Así es. Las investigadoras observan que en los ritos sumerios, el hombre es el objeto del placer. En los himnos a la diosa Inana, que hoy se consideran más antiguos de lo que se creía; a la mujer se la presenta como la dadora y conductora de la energía divina a través del sexo. Por tanto es también la creadora de la escritura sagrada llamada el Kundalini. Estos versos son los más bellos cánticos a la sexualidad.

Sin ir más lejos, en el libro histórico como que es la Biblia, el Cantar de los Cantares contiene versos de tremendo contenido erótico. En ellos es la amada, la hablante, la que seduce y canta a su amado.

LC: Hace muchos años que leí algunos de ellos, pero a escondidas. Ya sabes, la religión católica le prohíbe a la mujer leerlos. Y crecí en México, donde la iglesia católica manda.

ZH: En realidad se piensa que estos versos pertenecían a libros míticos, pero con la imposición más tarde del patriarcado no pudieron eliminarlos, y más bien fue un caso de “co-option” política. La religión moderna los interpreta como un canto de amor entre el creyente y la iglesia.

LC: Claro. La iglesia. La que a veces ve solamente por sus propios intereses y enriquecimiento, y la liberación sexual de la mujer no le conviene.

ZH: Al imponerse el patriarcado lo erótico y la escritura erótica pasó a ser dominio del hombre y desde entonces él es el que puede cantar a la sexualidad, al amor, al erotismo no sólo de él sino de la mujer. ¿Te parece esto justo?

LC: Claro que no. Pero en estos casos nunca se trata de justicia, ni siquiera de caridad, sino de conveniencia y poder.

ZH: En lo que respecta a la mujer latina. El hombre le ha impuesto la modestia y el silencio, según las editoras del libro Pleasure in the Word: Erotic Writing by Latin American Women, e indican que la política del patriarcado cercenó el derecho que desde tiempos prehistóricos le correspondía a la mujer como dadora del placer y de la escritura.

LC: Es decir que la mujer, al escribir cualquier tema que se le tilde de “erótico,” está aceptando que es la mejor exponente del erotismo. Pero el varón no puede aceptar la competencia, aunque hay muchos que lo ponen en términos de hacerle un bien a la mujer al reprimirla, Por el bien de la raza humana. Pero eso ya va cambiando debido a movimiento feminista. ¿Cuál es tu parecer?

ZH: Lo que las poetas, y me incluyo yo entre ellas, están haciendo es recuperar su sexualidad, al crear su propio lenguaje para expresar lo erótico, deshaciéndose de la palabra-masculina. Y como me inclino mucho a lo mítico, incluso en mis investigaciones, tengo la tendencia de buscar y encontrar fácilmente símbolos míticos.

Considero que en nuestro inconsciente colectivo se conservan esos mitos que son actualizados por el rito de la escritura erótica. Según Cassirer y Jung, la escritura, y especialmente la poesía, es el rito por el cual se actualizan los mitos.

Ahora te voy a contar una anécdota personal. La primera vez que fui a una conferencia a la universidad de Louisville, Kentucky donde me aceptaron tanto en ponencia como en poesía, me encontré por primera vez en el panel de poesía a dos poetas eróticas, Nela Rio e Ivonne Gordon, compatriota esta última. Por primera vez leía mi poesía erótica y con tanta vergüenza que agachaba la cabeza. Luego me dice Nela, Zheyla, no debes de avergonzarte de leer tus poemas eróticos y de allí me invitó a otra lectura en Washington D.C para poemas del cuerpo y más tarde, a otras conferencias y poco a poco fui perdiendo la vergüenza que ahora me siento una “sin vergüenza”. Nela ha sido una de las poetas más generosas con la que me he encontrado en el camino de las letras, ella fue la que me dio información sobre el Concurso Internacional de Poesía Erótica en la que le habían otorgado una mención honorífica especial.

LC: ¡Qué linda y generosa Nela! No tuve el placer de conocerla, pero tuve el gusto de conocer y compartir con Ivonne Gordon en San Antonio. No recuerdo bien el nombre de la conferencia, pero si el tema: Mujeres Poetas del Mundo Latino. Había otras grandes poetas de América Latina, al igual que Norma Cantú.

ZH: Poema a Nela

Nela contigo puedo jugar a las rayuelas

cantar una ronda infantil

"qué quería mi señorío

matun-tiru-tiru-lán"

-queremos ser poetas y cocineras,

matum-tirun-tiru-lán

Nela contigo vuelvo

a la infancia con una canción de cuna

"duérmete mi niño que tengo que hacer"

lavar estos versos ponerme a comer

Nela de niñas

yo te enseñaría

el "tun, tun ¿quién es?

el diablo con los siete mil cachos

o el ángel con la bola de oro"

que quiere una fruta o cinta

para ponerle colores

colocarla en un moño

Nela Correríamos nuevamente

una calle cualquiera

pero tomadas de la mano

para robar una estrella.

LC: Es como si se hubieran conocido tú y Nela desde la niñez, jugado juntas —desde siempre. Bello.

Cambiando un poco el tema. Veo que has publicado tu poesía en un sinnúmero de antologías y revistas, y en ediciones de tus libros. El único de tus poemarios que tengo es el último, Confesiones de un cuerpo/Confessions of a Body, editado por la Editorial Académica española en el 2019. ¿Cuáles son los títulos de tus otros poemarios?

ZH: 1) Pedazos, los recuerdos/Shattered Memories 2) Caleidoscopio del Recuerdo/Kaleidoscope of Memories 3) Confesiones de un cuerpo: Estaciones de Pasión/Confessions of a Body, Seasons of Passion.

LC: Me has dicho que conociste a Phan Thi Kim muchos años después de que terminó la guerra en Viet Nam. Pero escribiste este poema muchos años antes. ¿Qué te hizo escribirlo?

ZH: Otro ejemplo de la violencia contra la mujer ya desde niña, está fotografía icónica, en especial de una niña vietnamita desnuda, huyendo, de la guerra en Viet Nam. El poema que yo le escribí:

“PHAN THI KIM”, fue publicado en 2003 en la exposición de poesía Outspoken Art/Arte Claro,

dedicado a la eliminación de toda forma de violencia contra la mujer.

PHAN THI KIM

You have forgiven us.

Your fragile body running naked

stuck in my mind.

For years the picture

has been encrusted in my retina,

behind the infernal dust

that burned your body half.

Nic Ut save your image

for the world to see his crime.

I still don’t understand

why man has created war.

Tiny body, open mouth

arms flapping horizontally,

Behind, in front, in the center you,

the Christ, the city.

And still the world goes on

the same crime for ever and ever.

Phan Thi you are thirty three now

and you came to forgive us.

**********

LC: Ha sido un placer platicar contigo, Zheyla. Mil gracias por tus versos. Un cálido abrazo.

© Poetry by Zheyla Henriksen

Two Poems:

Rosario Moderno

and

Before Friday Comes Again

El primer misterio.

Oremos… por ellos.

Como eran en un principio,

Ahora y siempre,

Por los siglos de los siglos,

Serán:

Ulises.

Alhaja sin oro.

Marcos.

Canción sin coro.

Daniel.

Ladrido de lobo, sin morder.

Fue por mi culpa,

Por mi gran culpa.

Tengo la cruz en la boca,

Las perlas me ahorcan.

Soy la Soñadora Suprema.

La Llorona con Corona.

Lágrimas de Limón.

Haré una Limonada.

Trago amargo es el amor.

El último misterio.

Oremos… por ellas.

Como eran en un principio,

Ahora y siempre,

Por los siglos de los siglos,

Serán:

Maria.

Fruta sin semilla.

Cristina.

Flor sin espina.

Raquel.

Obra de arte, sin poder.

Por mi culpa, por mi culpa,

Por mi gran culpa.

Tengo a Jesús en la boca,

La serpiente me azota.

Soy la Celosa Suprema.

La Llorona con Corona.

Lágrimas de Limón.

Haré una Limonada.

Trago amargo es el amor.

I had ideas

But I forgot them

After a half drag

And a right swipe

I had ideas

But I forgot them

After a subtweet

Laughed, passed the blunt to the back seat

I had ideas

I had a concept

Maybe pretentious

But with endless potential

I had ideas

And then I double tapped

And then his hand grabbed

I had ideas

That slipped while I was grinding

While I was bumpin’

I had ideas

That would have blended better

Than this contour

Than this mezcal

Than this shopping cart

Than this dancefloor

My pout still stands though

Ideas come back though

In a different form, though

Still important to record.

I pray my attention span

Doesn’t evaporate

I pray my pen can hold my gaze

Before Friday comes again.

| Karen Valencia is a first generation Mexican American poet born and raised on Chicago’s Southwest side. A Northwestern graduate, Karen has appeared in Huizache, The Magazine for Latino Literature (2014) and most recently in the Literary Issue of Southside Weekly (2019). Karen is also a fashion stylist, model, DJ and co-creator of DESMADRE, a Latinx fashion styling collective. To see more of her work you can visit her website (karenvalencia.com) and to check out her other projects, follow her on Instagram (@karennoid). |

Dentro llevamos voces mixtas -- nuestro legado

(al modo nahua)

By Rafael Jesús González

La flor y canto que nos llega

es desarraigado --

se marchitan las flores,

se desgarran las plumas,

se desmorona el oro,

se quiebra el jade.

No importa que tan denso el humo de copal,

cuantos los corazones ofrendados,

se desarraigan los mitos,

mueren los dioses.

Tratamos de salvarlos

de las aguas oscuras del pasado

con anzuelos frágiles

forjados de imaginación y anhelo.

Dentro llevamos voces mixtas --

abuelas, abuelos

conquistados y conquistadores

— nuestro legado.

De él tenemos que escoger lo preciso,

lo negro, lo rojo,

cultivar nuestras propias flores,

cantar nuestros propios cantos,

recoger plumas nuevas para adornarnos,

oro para formarnos el rostro,

buscar jade para labrarnos el corazón --

sólo así crearemos el nuevo mundo.

Within we carry mixed voices

— our legacy

(in the Nahua mode)

The flower & Song that come to us

is uprooted --

flowers wither,

feathers tear,

gold crumbles,

jade breaks.

It matters not how thick the incense smoke,

how many the hearts offered,

myths are uprooted,

the gods die.

We try to save them

from the dark waters of the past

with fragile hooks

forged of imagination & longing.

Within we carry mixed voices --

grandmothers, grandfathers

conquered & conquerors

— our legacy.

From it we have to choose the necessary,

the black & the red,

grow our own flowers,

sing our own songs,

gather new feathers to adorn ourselves,

discover new gold to form our face,

seek jade to carve our hearts --

only thus can we create the new world.

| Rafael Jesús González es Poeta Laureado de la Ciudad de Berkeley, California/is Poet Laureate of Berkeley, California. Por décadas, ha sido un activista pro la paz y justicia usando la palabra como una espada de la verdad. For decades, he has been an activist for peace and justice, wielding the word like a sword of truth. © Rafael Jesús González 2019. |

Archives

July 2024

April 2024

February 2024

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

March 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

November 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

March 2017

January 2017

May 2016

February 2010

Categories

All

Archive

Argentina

Bilingüe

Book

Book Excerpt

Book Review

Boricua

California

Caribbean

Central American

Cesar Chavez

Chicano

Chicano/a/x

Chumash

Chupacabra

Círculo

Colombiana

Colombian American

Colonialism

Cuban American

Culture

Current Events

Death

Debut

Dia De Los Muertos

Diaspora

Dominican American

Dreams

East Harlem

Ecology / Environment

El Salvador

Emerging Writer

English

Excerpt

Family

Farmworker Rights / Agricultural Work / Labor Rights Issues

Flashback

Floricanto

Food

History

Identity

Immigration

Imperialism

Indigenous

Indigenous / American Indian / Native American / First Nations / First People

Interview

Language

Latin America

Love

Mature

Memoir

Memory

Mestizaje

Mexican American

Mexico

Nahuatl

Nicaraguan-diaspora

Nicaraguan-diaspora

Ofrenda

Patriarchy

Performance

Peruvian American

Poesia

Poesía

Poesía

Poet Laureate

Poetry

Prose Poetry

Puerto Rican Disapora

Puerto Rico

Racism

Review

Salvadoran

Social Justice

Southwest

Spanish

Spanish And English

Surrealism

Texas

Translation

Travel

Ulvalde

Visual Poetry

War

Women

Young-writers

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed