Extracto de Sintaxis Ilegal, poesías de Iván Argüelles en inglés y español |

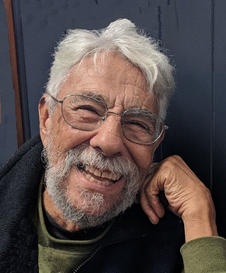

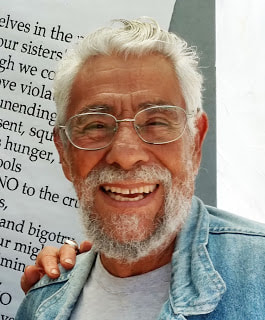

| Rafael Jesús González es Poeta Laureado de la Ciudad de Berkeley, California/is Poet Laureate of Berkeley, California. Por décadas, ha sido un activista pro la paz y justicia usando la palabra como una espada de la verdad. For decades, he has been an activist for peace and justice, wielding the word like a sword of truth. © Rafael Jesús González 2019. |

Archives

July 2024

April 2024

February 2024

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

March 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

November 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

March 2017

January 2017

May 2016

February 2010

Categories

All

Archive

Argentina

Bilingüe

Book

Book Excerpt

Book Review

Boricua

California

Caribbean

Central American

Cesar Chavez

Chicano

Chicano/a/x

Chumash

Chupacabra

Círculo

Colombiana

Colombian American

Colonialism

Cuban American

Culture

Current Events

Death

Debut

Dia De Los Muertos

Diaspora

Dominican American

Dreams

East Harlem

Ecology / Environment

El Salvador

Emerging Writer

English

Excerpt

Family

Farmworker Rights / Agricultural Work / Labor Rights Issues

Flashback

Floricanto

Food

History

Identity

Immigration

Imperialism

Indigenous

Indigenous / American Indian / Native American / First Nations / First People

Interview

Language

Latin America

Love

Mature

Memoir

Memory

Mestizaje

Mexican American

Mexico

Nahuatl

Nicaraguan-diaspora

Nicaraguan-diaspora

Ofrenda

Patriarchy

Performance

Peruvian American

Poesia

Poesía

Poesía

Poet Laureate

Poetry

Prose Poetry

Puerto Rican Disapora

Puerto Rico

Racism

Review

Salvadoran

Social Justice

Southwest

Spanish

Spanish And English

Surrealism

Texas

Translation

Travel

Ulvalde

Visual Poetry

War

Women

Young-writers

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed