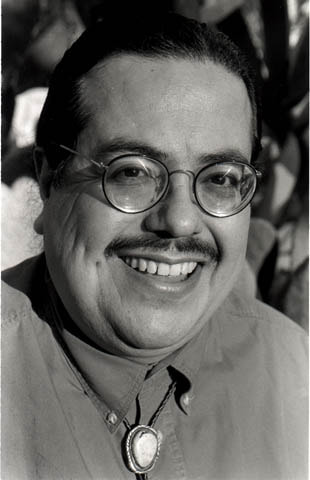

“The Jolly Chicano Poet |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

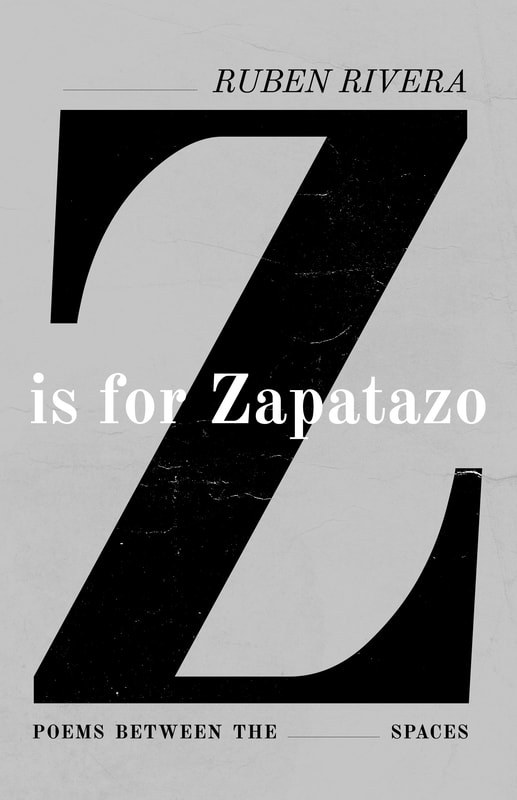

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed