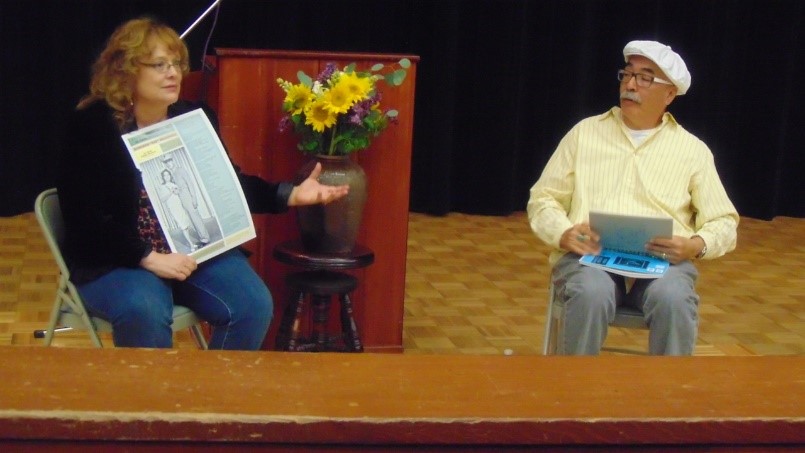

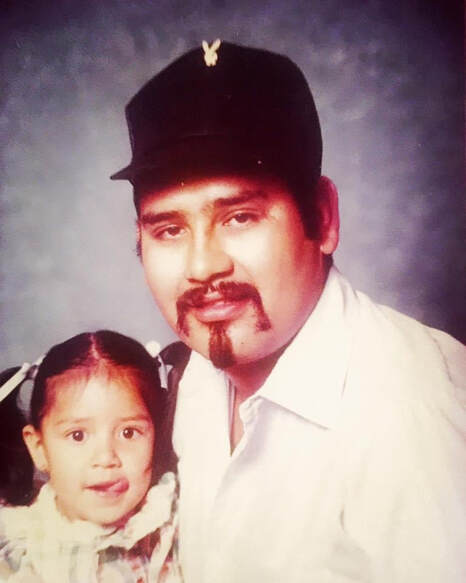

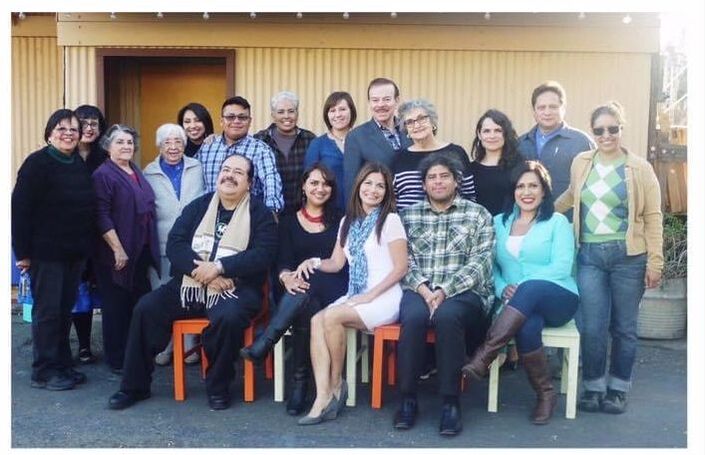

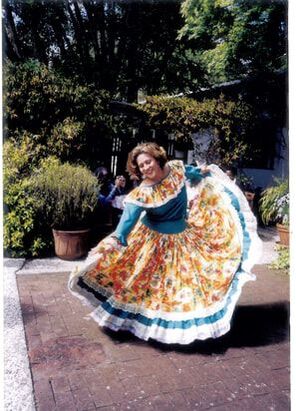

“Por escrito” Lucha Corpi (LC) entrevista a Graciela Brauer Ramírez (GBR), Catedrática jubilada de la Universidad Estatal de California en Sacramento. Poeta y narradora chicana, y trabajadora cultural incansable. Miembro de “Escritores del Nuevo Sol” en el Valle de Sacramento y de “Círculo de poetas & Writers” en la Bahía de San Francisco, con sede en Oakland. AZTLÁN – El lugar de las garzas LC: Querida Graciela, cómo se ve claramente, en la portada de tu libro están estampadas las garzas, aves que normalmente habitan a orillas de los ríos en California y en México: Algunos de los ríos más caudalosos se encuentran en el sur de México y precisamente en el estado de Veracruz y cerca de la Ciudad de México de donde eres originaria. Me fascinó ver que tu obra comienza con una descripción del Río Americano (the American River) que atraviesa de lado a lado la Cd. de Sacramento, capital del estado de California. Según la leyenda indígena mexicana, AZTLÁN era el lugar de origen de las varias tribus pre-colombinas, las que poblaban el continente de América, desde Alaska y Canadá hasta Tierra del Fuego en Sudamérica. A primera vista se podría también decir que EDUCACIÓN: Una Épica Chicana de la catedrática, poeta y narradora, Graciela Brauer Ramírez, es un libro de texto histórico. Ofrece una visión y cronología histórico-política de acontecimientos que se suscitaron en la Cd. de Sacramento, capital del estado de California, durante las décadas de 1960 a 1980. Al mismo tiempo, ofrece una vista panorámica del movimiento socio-político y pro-derechos civiles del pueblo México-americano en EE.UU., es decir de la población que se autodefine políticamente como chicanos. De una manera más general, bosqueja también el impacto de los logros de esta población, desde entonces hasta la fecha. Desde el punto de vista literario sigue las reglas de una epopeya clásica, es decir como lo fueran la Odisea o Ilíada en la antigüedad. Es un relato en verso y trata de las hazañas de héroes en tiempos de guerra y en defensa de su pueblo, su historia y cultura. Más aún, es la infra-historia de una familia californiana, con fuertes lazos culturales, literarios e históricos, con México y el sudoeste de Estados Unidos. Gracias. Graciela. Lucha Corpi Entrevista y plática: Lucha Corpi (LC) y Graciela Brauer Ramírez (GBR) en conversación. Influencias: En familia o comunitarias: LC: Tu obra culturalmente es parte de una tradición oral, pero lo es también de la literaria. Es en verdad, Una Épica Chicana, y una obra monumental. ¡Enhorabuena, Graciela! Ahora, cuéntanos un poco sobre tu niñez y adolescencia en familia. Sabemos que tu padre fue de gran influencia en ti, quien estimuló tu sed intelectual por el conocimiento y la lectura. Aprendiste a leer a los cuatro años. Entiendo que tu convivencia con otros parientes, en ambos lados, también fue muy importante. En familia, aparte de tu papá y mamá, ¿Quiénes más fueron de gran influencia en ti durante tu niñez? GBR: Como digo en mi libro, Una épica chicana, por las noches, en familia, nos juntábamos en el patio y cada uno decía poesías o contaba historias. Por ejemplo, a mi tío Homero le gustaban las historias del mar y de barcos. Después fue marinero. Mi tío Sergio siempre nos contaba la misma historia sólo le cambiaba los nombres de los personajes. A mí me subían en una silla y recitaba: “Mamá, soy Paquito, no haré travesuras…” Y también una que dice: “Guadalupe la Chinaca va en busca de Pantaleón su marido…” Dado que a los 2 o 3 años yo no podía todavía hablar bien, recitaba este verso a mi manera: “aupe anaca busca a neon maido…” Mi tía Elena, aun cuando ya estaba yo grande, se burlaba de mí imitándome, pues a esa edad temprana no podía yo hablar claro, pero, según yo, ya recitaba. También mi tía me decía que cuando terminaba yo les pedía aplausos al “púbico” (el público). LC: Me haces reír. Muy divertido. Ya entrando a la secundaria, ¿seguiste recitando poemas en público? GBR: Claro que sí. Ya de estudiante, en la secundaria, recitaba en concursos y en uno de ellos gané el primer premio al recitar de memoria el poema “Los Motivos del Lobo” de Rubén Darío el gran poeta de Nicaragua. Hasta la fecha, ya en mi vejez, aún recuerdo todo este poema tan largo. LC: Entonces, en cuanto a los lugares que fueron importantes en tu desarrollo durante tus años tempranos, sabemos que naciste y viviste en la Ciudad de México y que sufriste los calores y el bochorno del trópico en el puerto de Veracruz. En el prólogo de Educación: Una Épica Chicana, JoAnn Anglin, gran poeta y narradora, a quien también tengo el gusto y la honra de conocer, nos da algunos datos personales tuyos, pero bastante esquemáticos. LC: Si te es posible, cuéntanos un poco de ti, de tu vida personal antes de unirte al cuerpo docente de la Universidad Estatal de California (California State University at Sacramento-CSUS). GBR: Las gentes que tuvieron más influencia en mi infancia fueron mi papá y mi tía abuela Juanita. El me introdujo a la lectura, al grado de que cuando fui al kínder ya había leído varios libros de cuentos que él siempre me compraba. Mi tía abuela Juanita tenía una tienda de abarrotes a media cuadra de nuestro apartamento. Ella tenía su recámara arriba de la tienda. A veces ella me cuidaba o cuando iba a la tienda inmediatamente subía a su recámara pues ahí tenía muchos libros. Ahí leí: Corazón Diario de un Niño, Las Mil y Una Noches y muchas otras obras que aún viven en mi mente y que me han ayudado a sobrevivir. Un día mi tía me sorprendió mucho cuando me regaló estos dos libros y algunos más. También mi papá. Él era militar, y por algunas horas, también valuador en la mayor casa de empeño controlada por el gobierno. A veces tenían subastas y la mercancía que quedaba la repartían entre los trabajadores. Esta era generalmente de libros, los cuales él traía al apartamento. Entre esos libros leí, con ayuda de adultos, La Vuelta al Mundo en Ochenta Días, El Jorobado de Nuestra Señora de París y muchos más. Fui muy afortunada. LC: Nos has contado que debido al trabajo de tu papá, quién era militar, viviste en diferentes lugares. ¿Cómo afectó el pasar tu infancia y adolescencia en comunidades tan diferentes una de la otra? GBR: Primero, era una bebé y mientras que las mismas personas me cuidaran, no había problema. Después, cuando contaba con cuatro años, mi papá me ponía en el tren los viernes por la noche y mi abuelito me recogía en el puerto de Veracruz en la mañana del sábado. El regreso era viaje opuesto, por supuesto, de domingo en la noche a lunes por la mañana. También pasaba todas las vacaciones en la costa del Golfo de México, que era la costa veracruzana. Vivir en el puerto de Veracruz fue para mí una experiencia muy afortunada pues mi abuelito era una persona muy educada al haber estudiado en el seminario; había leído mucho. Con él aprendí bastante. También en Veracruz vivían mis tíos quienes eran muy adeptos a las poesías. Mi tío Carlos, por ejemplo, sabía muchas de ellas de memoria. En las noches nos recitaba versos de sus autores favoritos como Díaz Mirón, poeta veracruzano. Mi tía Estela recitaba en las escuelas. Aún recuerdo una de sus poesías favoritas que dice: “…espera la caída de las hojas.” Mi abuelito y su hijo mayor trabajaban en el ferrocarril me conocían y me querían bastante. A menudo, ellos me llevaban de viaje. Durante mis viajes la tripulación del ferrocarril me cuidaba. LC: Cuéntanos también de tu familia materna y de tu educación formal y adolescencia GBR: Cursé la primaria en El Colegio de San Ignacio de Loyola comúnmente conocido como Colegio de las Vizcaínas, una escuela católica en la Ciudad de México. Mis padres se divorciaron cuando yo tenía menos de un año. Mi papá tomó la responsabilidad de criarme. Él era militar así es que yo crecí regimentada, cosa que siempre le he agradecido pues aprendí disciplina, algo que me ha servido toda mi vida, y que él hizo con mucho amor. A los 15 años me fui a vivir con mi mamá. Ella era una famosa cantante de música ranchera. Mi vida con ella era excitante pues me llevaba a los teatros y estaciones de radio en donde conocí artistas famosos de aquella época. Por otro lado, ella era una persona muy extrovertida y se impacientaba mucho conmigo por ser yo sumamente introvertida. Con ella viajé en sus giras por muchos estados de México y lugares en los Estados Unidos como las ciudades fronterizas de El Paso, Texas y San Diego, California, además de Los Ángeles en California, entre otras. Desgraciadamente mi mamá y yo éramos demasiado diferentes. Ella era una feminista que a los 40 años se hizo torera aficionada; yo vivía dentro de los libros. Con mis padres crecí en dos mundos completamente opuestos. Sin embargo, en ambos mundos, todas mis experiencias fueron muy buenas. LC: En esta entrevista quiero hacer resaltar no sólo tu trayectoria poética-literaria sino también tu participación en el movimiento pro-derechos civiles y humanos del pueblo chicano en Estados Unidos. Al leer tu obra, me doy cuenta que tú fuiste testigo y participante en muchos de los acontecimientos que describes en tu libro durante “el movimiento chicano”. Cuéntanos sobre esta importante época de tu vida. GBR: Mi participación en los primeros años de pertenecer al movimiento chicano, fue la siguiente: ayudaba en lo que podía como organizar eventos poéticos, así como los Simposios de Pensadores del Tercer Mundo y otros más. También ayudaba en sus funciones para recaudar fondos como ventas de pan dulce, tacos etc. Me daba de voluntaria para ayudar a organizaciones como CAMP (College Assistance Migrant Program) entre otras. También tuve en el barrio, en el Washington Neighborhood Center, un programa tutorial en el que llevaba estudiantes de la universidad a enseñar a los niños. Lo óptimo de mi participación fue cuando formulé y comencé a enseñar el curso “La Mujer Chicana” en el Departamento de Estudios Étnicos, de la Universidad Estatal de California en su campus de Sacramento-CSUS. El gran poeta y activista chicano, José Montoya, era catedrático en este mismo departamento. Después de haber recibido algunos reconocimientos por mi participación en el movimiento chicano, mi mayor orgullo llegó un día cuando José Montoya me llamó y me dijo: “Gracias, Graciela, porque nunca nos has dejado”. Este ha sido el mejor reconocimiento que he recibido en mi vida. José tenía razón. He creído siempre que es un derecho de todo ser humano tener acceso a la educación formal. Me uní al Movimiento Chicano Pro-derechos humanos y civiles. Para los chicanos, acceso a una buena educación era lo que más deseaban. Sentí como si un imán me atraía hacia ellos. También a José Montoya siempre le viviré agradecida. El organizaba programas y recitales de poesía en la universidad. Fue él quien me apoyó é invitó a leer mi obra poética en público, por primera vez en mi vida. Cómo recuerdo cuanto sufrí, y las ansias que me causó, pues tenía demasiado miedo de leer en público. Yo había leído en programas escolares pero nunca en programas en público en general. José lo notó y con sus palabras me animó mucho. Al fin, temblaba pero lo hice. La Poesía de Graciela B. Ramírez REBOZO Rebozo que humillado te escondías, mas con la revolución volviste altivo en los hombros de Frida** quien sin miedo te sacó de penumbras ensalzando los colores brillantes de tus hilos. Así volviste a colorear las fiestas adornando con gracia a las mujeres quienes ahora en cuerpos te lucían o zapateando en moños te enredaban. Rebozo que en los campos de batalla de la intemperie protegías a guerrilleras y en las noches cubriendo a los amantes creabas mundo privado en que chasquidos de besos resonaban en el aire y después el amor bajo de ti hacían porque quizá la luz del sol Ya no verían Rebozo, con tus hebras acaricias de las futuras madres sus vientres esponjados, entibiando matrices, dando calor a fetos, enlazando dos seres en comunión sagrada Cordón umbilical de madre y niño porque cuando ellas cargan, cual marsupias, a sus tiernos infantes, ellos saben que no hay peligro alguno porque tú con firmeza los sostienes. Y también con amor cubres los senos cuando el pequeño cual gatito tierno mama la tibia leche de su madre y arrullado con ritmos de latidos sueña envuelto en respiros melodiosos y despierta al sentir hondo suspiro y se ve reflejado en dulces ojos. **Nota Bene: Frida Kahlo volvió a hacer famoso el rebozo de seda mexicano. A este rebozo también se le conoce como Rebozo de seda de Santa María, el pequeño pueblo en el estado de San Luis Potosí, en donde se encuentran los telares de rebozos. Ahí mismo también se pueden ver los sembradíos de las plantas de las que se alimentan las orugas que el público en general conoce como “los gusanos de seda”. Frida también mostró el modo, arte y orgullo de portarlo el rebozo. Fue precisamente durante las décadas de los años sesenta y setenta que las mujeres chicanas, México-americanas y latinas volvieron una vez más a hacer legítimo el uso del rebozo, tanto el de algodón como el de seda. -LC Tlaloc There came a day when your gigantic statue was moved from its birth place to Chapultepec’s sacred emerald forest where hundreds of crickets sing for you the eternal welcoming song Slowly, so slowly 168 tons of stone moved through Tenochtitlan’s streets cradled in the specially-built trailer going slowly, So slowly. During the night, work crews disconnected and reconnected electrical wires needed because of your 23-foot height. Perhaps you laughed At all the attention From the multitudes After the 30-mile journey, came the huge explosion, like a Big Bang, embedding our memories back in our city recalling years of invasions, centuries of deep pain. But finally, the gift of spiritual Renaissance as you passed through the Zócalo, The Great Temple, El Templo Mayor. At that precise instant came the deluge, your fertility water, your life-giving water, your survival water, your baptismal water, your melting jade rain that poured over us running in force through our city washing us in blessings and forgiving waters through archeological sites, the burial homes of your ancestors the burial homes of our ancestors. Tláloc, the Great Tláloc: The eagle and the serpent Acknowledged you As the Lord of the Third Sun, As God of all Water. PINCELADAS Instantly becoming one With the new born moon And the eastern star All of a sudden Autumn smiles Reddish leaves Cosumnes River Witness in silence Courtship of cranes The broom Escapes from my hands Dishes Look at me with anger Only the pencil Calls me by my name Magic of Jazz Is for me Sensuality and Spirituality Interwoven Only the pencil Calls me by my name Rain, flamenco woman Dancer Stamping On the roof of my house. **CHICANOS Y LA LENGUA Esta es la historia de la gente… que nace o emigra en retroceso, a esas tierras que ancestros disfrutaron, a lugares viniendo de regreso, que ejércitos extraños conquistaron, sitio donde las grullas con su beso y su baile, colonias iniciaron. Esta es la gente que con ansia busca, un lugar en el sol, cosa muy justa. ... **EPIFANÍA CHICANA Aztlán renace, del chicano cuna su núcleo de las cuatro direcciones aurículas en Utah y Colorado ventrícula del sur en Arizona y otra en Nuevo México hechicero, Aztlán cuyas arterias cristalinas de estrellas salpicadas son Ríos Grande, Colorado y también el Sacramento. ... **LC: Estrofas de Educación: Una Epica Chicana, p. 3 y 24 GBR: Aquí estamos José Montoya y yo esperando una de las cuatro ceremonias pre-Colombinas en Sacramento (la de los niños, la de las jóvenes o Xilonen, la de los jóvenes y el Día de los Muertos). En los setenta José fue uno de los iniciadores de ellas y tuvo a su cargo el altar del norte o el de los viejitos. Yo empecé en el sagrado círculo como a principio de los ochenta y duré en la dirección del norte con José como 25 años o más que fueron inolvidables pues pasar más de 9 horas en compañía de José preparando el altar, marcar el círculo con polvo de maíz, mantener el fuego en el salmador, esperar al grupo que iba a recibir consejos y dárselos fue una de mis mejores experiencias. Con él y los Chicanos aprendí muchísimo. Generalmente leo con mi grupo “Escritores del Nuevo Sol”. Yo soy la que organizo los recitales poéticos en Sacramento. Nuestros programas son en lugares como “Sol Collective”, “Luna’s Café”, y “The Poetry Center”. Hace tiempo iba con mi grupo de escritores a leer en las ciudades de San Francisco, Stockton, Yuba City y otros lugares en California. También en ocasiones leo como parte del grupo al que también pertenezco “Círculo de Poetas & Writers” con base en Oakland, California y miembros en varias ciudades del norte de California. LC: ¿Cómo y dónde pueden los interesados conseguir el libro Educación: Una Épica Chicana?

1) De la autora: email: [email protected] 2) Sol Collective, Sacramento, California LC: No hay duda, apreciada Graciela, que has tenido una larga y fascinante carrera como catedrática y poeta. Me encanta tu actitud ante la vida: siempre optimista. Eres de gran inspiración a todos nosotros, tanto a los “Escritores del Nuevo Sol” como los miembros del “Círculo de poetas & Writers”. Mil gracias por tu participación en esta serie de entrevistas, patrocinadas por el periódico bilingüe Somos en escrito y por “Círculo de poetas & Writers” en la bahía de San Francisco. **En especial, mis más sinceras gracias a Jenny Irizary of Somos en escrito, por su paciencia y asistencia técnica en esta serie de entrevistas mes tras mes. Abrazos, Jenny. **Igualmente, gracias a Paul Aponte y Betty Sánchez de “Círculo de poetas & Writers” (SFBA) y “Escritores del Nuevo Sol”, Sacramento por su ayuda con las fotos que aquí se incluyen. © Poetry, Graciela Brauer Ramírez, de su libro: Educación: Una Épica Chicana

0 Comments

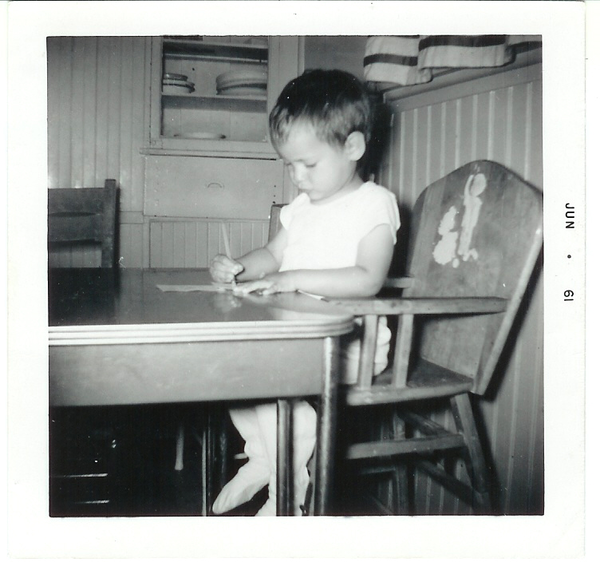

JoAnn Anglin JoAnn Anglin JoAnn Anglin THE POET: IN HER OWN WORDS CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE I think I was just under 3 years old, and already had 2 younger sisters, and we lived in Bremerton, Washington. My Dad was a truck driver. We were all three baby girls in a small, crowded room — it could even have been some kind of back porch, it was very light, sunny. I was standing in my crib, and my dad came in. I recall him looking at us, smiling in delight, as if he was thinking, Look at what I’ve created! All my memories of those early years, up until the time I was around 11 years old, are pretty good. Due to the Second World War, we did some moving around. My dad was drafted into the Navy, so my mom took us back to their home area of South Dakota, where we lived with her parents for a while out in the country. Then my dad was stationed at Treasure Island and we came out here and lived in Hayward for a while. My mom was fine with driving back and forth cross country. Once he shipped out, she moved to Sacramento; we lived in the garage of an old friend of hers who rounded up beds and cribs for us. My dad was probably a bigger influence on me than my mom. Later, some of my first poems would be about him. We had good conversations and he always paid more attention to what was going on in the world. I am a feminist, but always interested to hear the male point of view. I don’t write about those specific locations, but I do realize that I became an observer at an early age, Some might find this now hard to believe, but I was a pretty quiet kid and on the shy side. Usually very obedient. We were strong on rule-following. I can look back at all those years like a slide show, scene after scene, in my head. Going to school was where I became more outgoing. They were Catholic parochial schools from 1st grade through high school. At first, we lived in public housing. In retrospect, it was kind of dumpy, but with a post-war housing shortage, everyone was in the same boat. This was before the days of air conditioning, and the insides were small and crowded, so we all spent a lot of time outside. I walked through Southside Park to get to Holy Angels School, and we played at the park. Before I started school, my mom taught me how to print my name. I was satisfied to spend a lot of time on my own. I wasn’t rebellious, but I was pretty independent. In 3rd Grade, with my dad’s VA-FHA loan they bought a house in a little subdivision, with railroad tracks and empty fields around us. I think the religious sisters who taught in our schools were okay, but favored well-behaved girls. In those days of corporal punishment, even I got my hands whacked with a ruler a few times. But the boys got the worst of it. Even worse, in our school at least, there were often 50 or more kids to a classroom. One thing my sisters and I recall is that there was no sharp demarcation between not-reading and reading. It was just something we flowed into, like a creek into a river. Also, we were strict-practicing Catholics. It’s almost 50 years since I left the church, but I have a great sympathy for writing that includes spiritual aspect, including the idea of mystery. And many of my poems directly or indirectly refer to Catholic terminology or ceremonial practice. About age 10 or 11, I read a lot and loved movies and wanted to make my own stories. Of course I didn’t understand about plot or structure, so the stories might start with a description of a heroine, but then just trail off with no conclusion I loved words for as long as I can remember, and would read everything, breakfast cereal boxes to comic books to Reader’s Digest. I read the newspaper funnies and, before long, some articles and letters to the editor. In high school I wrote some letters to the editor myself. I generally got good grades, but don’t recall creativity being encouraged. The emphasis was on learning the correct answers and responses, especially related to the catechism. But I will always be grateful to Sister Mercy in 7th and 8th grades for giving credit for poetry memorization. We were part of the pre-Boomer generation, my friends and I would create little skits or dances and might perform them at lunch time on rainy days when we had to stay in the classroom. I didn’t know anyone who took piano lessons, although I took tap lessons for a few years. I would add that I was very daydreamy, but that fantasizing didn’t get written down much. During elementary school, drawing was a more usual artistic outlet for me. The topic of fairness was on my mind from an early age. This would come up in my assignments for speech or debate classes. And I always wished to have more beauty in my life. I also saw life as struggle and that often surfaces in my writing. In high school, after turning in some essay assignments, I was recruited to be editor of my school paper. I became deeply involved in all kinds of writing then — interviews, reviews, profiles, etc., and also began to understand about layout and some basics of journalism. This was never seen as a real career prep, though, just an extracurricular activity. POEMS Easter 1999, to my Dad I’m thinking of you and thinking of Mom, And many Easters now long gone; Thinking of eggs and candy rabbits, Of jelly beans and pastel baskets, Of Lenten churches, purple-clad, And Easter pancakes we sometimes had. From out of the house, we’d all of us file And into the old green Plymouth pile. Some of us sang then, in the choir While showing off our new attire – Our shiny shoes and new straw hats – and briefly put aside our spats. I remember those days, and I’m glad we had ‘em; Memories that can still warm and gladden. Now, thinking of flowers and alleluia, Again I wish Happy Easter to you! Neri’s Sculpture: “Nude” (Written sometime in the late ‘90s) She isn’t whole, doesn’t know if she ever will be. Since her shatter, she has started to disappear. Her once-strong edges of sweeping curves, elegant angles demarcated her world. Sometimes she misses what was solid, sometimes not. Unexpected barbs cannot hook her now, nor tear her substance. As the abrupt world flows around her shards of her being chip off. She is amazed at what can pass through. Once somebody’s memory, now a faded dream of essence that uses space, shifts, casts shadows. Exquisite tension holds the stones of her in shapely structure, a cairn. She tries to move in fluid shimmer gatherer of river gravels that lead to dissolve, shuffling rocks that glint and reflect what pours into yet never fills her. Somehow the shaky sculpture keeps moving forward. She is seen as through frosted glass, and knows well the force of her yearning, but not whether she yearns to be whole or to fully dissolve. The Chagall Lovers October 2003 (Written for Arturo and Christina Mantecon) Ascending each evening, they float in the sky drawn up by kisses and each other’s eyes. We hold our breaths, but they are buoyed up above city streets on thermals of love Their bouquets trail petals marking their flight through satin blue evenings of levitation They stair step the roofs in the forest of dusk glisten as moon rise whispers its secrets And gaze past their radiant halo songs to stars chiming softly in heaven’s seas Tender as tulips emerging from earth they hold each other in night sky gardens Up there with fiddlers and gods and devils dancing with goats and calves and doves Nourished on scents from the orange trees below veiled in the rapture of fortunate love Their hands round the necks of roosters and horses, tangled in garlands braided in manes, The town beneath is a chorus of wishes that rise up like bubbles, like scarlet balloons. They smile. They smile at gravity that has nothing to do with them. Secrets of a Babysitter As if she were a robot with no curiosity, They wave themselves away Sure she has homework, they say it’s okay To have some snacks or use the telephone. She bathes the children, reads to them Spoons ice cream into slack pink mouths. Once they are in bed, she eyes drawer pulls And door handles, cupboards and latches She knows where the crème de menthe Sits stickily on the pantry shelf Where the glossy Polaroids are kept In the back of the lingerie drawer While children sleep she fingers coupons Foreign coins and keys in the kitchen drawer Examines paperback books, CDs and videos Turns album pages, sits at the computer Shakes each pill bottle in the medicine cabinet Removes and pockets one from each prescription. Sprays herself with golden scents from a mirrored Tray, slips on a silky camisole that skims her nipples Smacks her lips as she tries on lipstick in shades She’d never wear, wonders at its fruity, slippery taste. The News March 2007 No news is not good news No news means something is in a gather of foreboding, lurks under snarled brush, just beyond the darkened horizon. No news means a smudge on the old photograph, a missed chance to reclaim that patient sepia image. Stains only worsen when rubbed. To fray lacks the order of ravel. There was a song, a vinyl record, a larkish trill of hope rising, now scratched by disregard. Something once held with care set now among danger. Imagination both helps and hurts. News keeps breaking into or out. Patch the shattering — tape or spackle may soften the force, but it comes. Seepage will enter, its outline remain. Boy’s Ranch November 2010 Before you arrive at the gate, you have wound through the clefts of pale yellow hills. You have seen flocks — wild turkeys, then Canada geese — and shallow pools reflecting blue skies. Further, like old men, crouched turkey vultures pause in their pavement feast. Beyond fences: cattle, tilting trees. Drive on through the oak grove where a loping coyote stares back. The gate arm lifts, lets you pass. Not such a bad place, you say at the last curve, as jays and woodpeckers fly through the double rolls of razor wire atop the 20-foot steel fence. My To-Do List April 2013 I checked off the decision to have two failed marriages. And children who lacked confidence in me: checked. The pet dog who ate the poison. Checked. There was the boss who made me cry. Check. The one who made me crazy. Check. Plumbing that corroded, beloved serving dish that broke. Check. Wrong turn that took me out of my way for two years. Check. Many checks for arguments on religion, race, sex, politics. Laughing in the wrong place. Saying Yes, saying No. Saying too much. Not enough. Check, and check. Unfiled income tax. What I owe family, former lovers. All checked off. Sleeping one more time with that man. Not sleeping with another. Saying I’m sorry too often. Double checks. Saying ‘sleeping with’ instead of sex. Saving the money, getting the cheapest substitute. Oh yeah, check. Fearing dogs and horses. Check. Smoking, check. Being persuaded, checked off again. In heavy ink. The days I don’t know who I am. Or why. Checking. Then, checking in too late. Checking out too soon. Source June 2015 Was I, then, in her? That serf girl, many centuries past, who hauled hay. Potato digger who sought small branches in the woods. Who paused to stand, wipe sweat from her brow. Was there ever a wondering of what lay in far castle, or further down the road? Probably an unwilling or unwanted suitor, to plant in her as she planted beans for another crop, wondered how much to raise, how much to keep, or pass on to the owners. And what of her child, or several, wrapped and slung against her soon worn body? And that child’s child? And so on. Where in me is planted the something of her? In how I pause to touch a day lily, to smell a melon, to note the lowering clouds? In how I have birthed children? And now, these poems, planting words in a line for her who could not read. Word of Mouth March 2016 I watch you sleep and lay beside you and want to go where you go, behind your eyelids. At times, you murmur soft indistinguishable sounds, urgent but amused, and I know you are not speaking to me. I try to imagine that language, that realm: if you are in a cabin on the mountain, or on the mountain looking birds in the eye. They would understand you, shy looks and cocked heads. Trust. Your voice resembling chirps, assenting to flight that’s regardless of wings, needs nobody. You start a little. You must be tasting the air, finding the currents, riding the updrafts. I want to be the one you return to. You can always land on me. A Day Muy Frio (date unsure) Como esta? Estoy bien. Oh yeah? Explain, por favor: Where is your sombrero? Your jaqueta? Your dinero? Donde es el carro, to ride to the supermercado? Donde es tu amigo? Captured by la migra? NEWS poem: (January 2020) “Inmates Released into ICE Custody” What do they try to carve when they slice this man away? What shape beautified by loss of his hands and eyes, when he becomes swiped off leftover clutter? Look for the resignation, sour, like rain’s stain already marking his worn surface. Instead of putting away the pain, and anointing what has healed, their hands rip off the new skin, throw it to the desperate dogs.  Escritores del Nuevo Sol anthologies Escritores del Nuevo Sol anthologies PLÁTICA: JoAnn Anglin (JAA) and Lucha Corpi (LC) in Conversation: LC: By circumstance, being an immigrant wife in the Bay Area, having no family here, being the mother of a young child, and years later going through a divorce, I began to write just as an exercise on spiritual and mental survival. I needed to know who I had become after getting married, and coming to the U.S. So many questions I had to find answers to. I felt that putting my feelings and life experience in the U.S. in writing would help me to make sense of my life and survive emotionally. It did. And I discovered I was a poet and writer in the process. You’ve told me the following about your beginnings as a writer: JAA: We had no creative writing classes (in high school), no literary journals. On my own I wrote poems, which I rarely showed, and song lyrics which I never showed. These were mostly imitative of popular music, show tunes, or church hymns. It would take community college to really open my mind and awareness of other creative or philosophical paths. My reading expanded, sometimes via assignments, and sometimes from recommendations from other students. Sometimes at home, I would want to talk about the reading, much as I’d liked to retell the movie stories when younger, but my interests made me the ‘odd duck’ in the family. LC: Was there a mentor/Teacher? Other poets at the time, from whom you learned your craft? JAA: I wish I could say yes. One community college English teacher, Margaret Harrison, saw potential in me. I can see this looking back. She wanted me to apply to Holy Names College in the Bay Area, but I was positive this wasn’t something my family could afford. I knew nothing of scholarships, loans, or work-study. I didn’t see a way. I never saw a counselor. I soon dropped classes so I could work and afford a (junky) car. I even went to the draft office of the Navy, but was discouraged from joining. By age 20, I was married and pregnant. My husband’s story was similar. Later, after divorcing, we both finished college, me graduating with my BA at age 41! LC: You are a member of Escritores del Nuevo Sol group in the Sacramento area. Later you and some of the poets in Escritores also became members of Círculo de Poetas y Escritores in Oakland and the East Bay Area, including Santa Cruz. The late Francisco X. Alarcón was instrumental in establishing both organizations. As a matter of fact, I was invited by Francisco to attend a workshop-meeting of Escritores. I met many of you there. I was very impressed with the group. I am also very impressed with Círculo de Poetas y Escritores members: Could you share how and when you and Francisco X. Alarcón met? JAA: I have to give huge credit to La Raza Galeria Posada, the Latino Art Center in Sacramento. I became aware of their work when I was a public information officer for seven years at the California Arts Council. At the time, I knew vaguely of the Royal Chicano Air Force, the Chicano artists group, and of José Montoya and Esteban Villa. A couple of my co-workers were the artists Juan Carrillo and Loraine Garcia, and also Tere Romo and Josie Talamantez, so my consciousness was really being raised in this area. I began going to public LRGP events, one of them a poetry reading, organized by Galeria board members Art Mantecón and Francisco Alarcón. At the reading, Francisco announced the decision to start a writers’ group, the Taller Literario. The next week I called Tere Romo who became the Galeria director and curator. I asked if I could join, although I’m not Latino. Her answer: of course! Later the name was changed because people were confused by the word Taller when wrongly interpreted as referring to height. As I recall, Francisco and Art came up with the name of Los Escritores del Nuevo Sol, mainly because of Francisco’s fascination with the Aztec calendar. José Montoya stressed to us the need for preserving Latino arts and literature. We met monthly at LRGP, eventually having public poetry readings, usually related to major holidays – Mother’s Day, Day of the Dead, and such. When the Galeria went through some major inner turmoil, we began to meet at members’ homes. I cannot give enough credit and praise to Francisco Alarcón. Whether personally, socially, in poetry, or in politics, he was the most generous, kind, and forgiving person I have ever known. And I still remain in awe of his talent and energy. I believe that he was at times subjected to prejudice due to his accent or to his being gay. If he felt bitter about it, he never turned that bitterness on anyone else. Like others who knew him, I will never stop missing him. When the Crocker Art Museum hosted the Latino art exhibit, Our America, he invited several of our most active Escritores to be part of a project of ekphrastic art – each participant choosing a painting to inspire a piece of poetry. He also drew on his friendship with and knowledge of poets throughout California, particularly the Bay Area, which led to the positive interactions among the two areas. Some, reluctant to let the interaction fade, later founded the Círculo. We continue to be enriched by it. LC: How has (or not) being in the workshop helped you focus on your poetry in a more productive way? JAA: One major thing: my membership in Los Escritores made me realize that my aptitude was for poetry, not fiction. We took turns facilitating exercises at our meetings, and I began to understand better the difference between words spoken and words on the page. Sometimes I’d bring a poem to read, and realize as I read it that segments of it, or just one word, didn’t really work. One of those exercises, by the way, was to give human personality to a non-human object. Francisco’s poem was called “Laughing Tomatoes,” which inspired him to write a series of related poems and became the title of his first children’s book. He also urged us to put together our first anthology of writing by Los Escritores. LC: I love your “My to do list,” poem. Do you remember what you were doing when the muse showed up? What was the first line, the first imagined “when”? JAA: Thank you! Interesting that you refer to the muse. I recently read a writer’s comment that if you wait for the muse, you will never write. However, that poem did come to me more easily than most. I would say that the more you write, the more you will be able to write. In this case, I had made an off-hand jokey remark about something that I’d have to put on my To Do list, and then that the list was pretty long. I followed that train of thought and the poem came together rather quickly, with fewer drafts than usual. Audiences always like it, too. LC: As a published poet, what advice would you give to younger poets who are just beginning to make their poetry known and establish their authorship? JAA: Write a lot and submit a lot. Read your work at open mics. Read what others are writing. Anthologies are wonderful for this. Do not be discouraged by rejection. It may or may not mean your poem needs more work. Often you will realize that your poem wasn’t quite right for one publication, but will be perfect for another. I have heard of poets submitting a particular poem dozens of times before it’s accepted. I had an instructive exchange at a writing conference a few years ago. During a break, somebody next to me at a table heard I was from Sacramento. An editor, she asked me if I knew Indigo Moor. (He later became our poet laureate.) She said, He’s a wonderful writer. She had been a judge in a contest he submitted to. He hadn’t won the contest, but his name had become familiar to several people who would be paying attention next time his poems came across their submissions desk.  SHORT BIO JoAnn Anglin has taught poetry writing in schools, at Shriners’ Children’s Hospital, for a program with Crocker Art Museum, at a senior facility, and most recently, for 8 years at California State Prison, Sacramento (New Folsom). JoAnn received a District Arts Award from the Sacramento City Council and the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors. A coach for 10 years for Poetry Out Loud, she is a member of California Poets in the Schools (CPITS), the Sacramento Poetry Center, the Círculo des Poetas y Escritores, and Los Escritores del Nuevo Sol/Writers of the New Sun. Several journals and anthologies have included her poems, most recently, The Los Angeles Review of Books. LC: Also, are you participating in any programs/readings in the area in the near future? How can people contact you about future programs and presentations? Do you have a newsletter? E-mail? Please tell:

JAA: The pandemic has pretty much stopped everything for now, although I’m encouraged with what people are doing via the ZOOM platform. A local publisher, 3 Bean Press, published my chapbook Heat in late January. I had one reading, and another scheduled, when everything was shut down. My work at the prison is now being done in a remote learning format and I really miss the in-class participation. Once the world evolves into whatever new shape it takes, I’d love to do more readings. My email is: [email protected]. LC: It’s been wonderful getting to know you through our mutual work with the Círculo de Poetas y Escritores, JoAnn. Mil gracias, JoAnn. Hasta pronto. ADELA NAJARRO THE POET: IN HER OWN WORDS I was born in San Francisco, and then around the age of four or five we moved to the Los Angeles area. We lived in many L.A. suburbs, Downey, Pico Rivera, Cerritos, and Torrance. We moved around a lot. I went to a different school almost every year. I learned to adapt and understand U.S. suburban culture. I also learned how all fluctuates and is indeterminate. My love of writing and ability to play between two languages arose from the randomness of my childhood. My early years were filled with what can best be termed chaotic love, and so I came to understand how the world is not set in one place, language, or mode of seeing, which just happens to be the perfect upbringing for a poet in a post-modern world! I have done a lot of inner work analyzing and articulating my childhood. My family, my memories, mi pasado, fuel my poems, though perhaps not directly in a one-to-one translated narrative. My early memories focus on my father. In one, he is carrying me from the car to the house. My head rests on his shoulder and I have my arms wrapped around his neck. We lived in San Francisco, at the time. We are going up the stairs to the door. In the other, I am in the same doorway, and someone asks my name. I reply “Adelita.” He tells me that my name is Adela and that Adelita is a term of endearment used in the family. Of course, he didn’t use those words since I must have been around four years old and this would have taken place in Spanish. I also have a memory of standing at the top of a street in San Francisco and looking down. I fear falling. My parents and grandparents were born in Nicaragua. Some of my cousins were born here in the U.S. while others were born in Nicaragua. Nearly all family members are now living in the United States. I’m sure there are a few distant cousins in Nicaragua. I don’t know them, but I would like to. Instead, what I do is travel to Nicaragua through my imagination—what was Nicaragua like for my mother, my father, mis abuelas? I love to imagine los pericos in the tropical rainforest and iguanas sunbathing in the branches of barren trees. I have always written. I have memories of writing poems in elementary school. I write to understand my place in the world THE POET'S BIO Adela Najarro is the author of three poetry collections: Split Geography, Twice Told Over and My Childrens, a chapbook that includes teaching resources. With My Childrens she hopes to bring Latinx poetry into the high school and college classroom so that students can explore poetry, identity, and what it means to be a person of color in US society. Her extended family’s emigration from Nicaragua to San Francisco began in the 1940’s and concluded in the eighties when the last of the family settled in the Los Angeles area. She currently teaches creative writing, literature, and composition at Cabrillo College, and is the English instructor for the Puente Project, a program designed to support Latinidad in all its aspects, while preparing community college students to transfer to four-year colleges and universities. Every spring semester, she teaches a “Poetry for the People,” workshop at Cabrillo College where students explore personal voice and social justice through poetry and spoken word. She holds a doctorate in literature and creative writing from Western Michigan University, as well as an M.F.A. from Vermont College, and is widely published in numerous anthologies and literary magazines. Her poetry appears in the University of Arizona Press anthology The Wind Shifts: New Latino Poetry, and she has published poems in numerous journals, including Porter Gulch Review, Acentos Review, BorderSenses, Feminist Studies, Puerto del Sol, Nimrod International Journal of Poetry & Prose, Notre Dame Review, Blue Mesa Review, Crab Orchard Review, and elsewhere. POEMS FROM TWICE TOLD OVER Early Morning Chat with God This morning I’m back to asking for patience. With my cup of coffee I sit outside to say hello to you God, my Jiminy Cricket, my salsa dancing quick-with-a-dip amigo. We have a very collegial relationship. I laugh at all your jokes and praise the wonders of a sky’s watercolors. I know you like me, a benign affection and tolerance as I run around like a chicken with its head cut off, a truly gruesome image, nevertheless hilarious like a grisly cartoon. The blood spurting. The body winding down to zero. The crashing into unforeseen objects. I think if I were back on my great-grandmother’s farm, the farm that I know only through stories my mother tells of Nicaragua, Bluefields, a tortilla filled with just enough, and I saw the long scrawny neck and the axe, I would be sick to my stomach: the aimlessness of her final strut, the reality of blood loss, her claws scratching the dirt, kicking up rocks, a panic. But when she stops, into the pot she goes. A meal, what we need to continue, her flesh simmered off the bone. Truly delicious in a tomato sauce flavored with green peppers and onions. Transformation. The feathers plucked, soil and dust washed away. The table set. Goblets of red wine, white china plates, a cast iron pot twirling a bay leaf scented steam. Then a prayer and gratitude that we have enough to make it through another night alone, a night filled with longing whispers and the turbulence of dreams. Between Two Languages Misericordia translates to mercy, as in God have mercy on our souls. Ten piedad, pity us the poor and suffering, the lost and broken. Have mercy. Ten piedad. Misericordia, a compassionate forgiveness, carries within miseria, misery, the stifled cry on a midnight bus to nowhere, and yes, the hunger, a starless night’s piercing howl, the shadows within shadows under a freeway overpass, the rage that God might be laughing, or even worse, silent, gone, a passing hallucination. Our nerve-wracked bodies tremble. Our eyes have trouble peering into night. Let us hope for more than can possibly be. Señor, ten misericordia de nosotros. And if we are made in the image of God, then we can begin heading toward the ultimate zero, the void that is not empty, forgive ourselves, and remember the three seconds when we caught a glimpse of someone else’s stifling cry. Compassion, then miseria, our own misery intensified by the discordant ringing of some other life. Our ultimate separation. Our bodies intolerably unable to halt the cacophonous clamor of unanswered prayers. But nevertheless we must try for no reason at all. Once more, Señor, ten misericordia de nosotros, forgive us for what we cannot do. Redlands I'm coming to the conclusion that I'm simple, like my mother, my grandmother, father. All of them from Nicaragua where time goes back further. Here, wagons and rifles, the prairie plowed into fields of soybeans and sunflowers. Sunken wood barns and tombstones rattle as a six-by-six tractor-trailer rumbles through exit 41a and on past peach cobbler, a shot of Jim Beam Whiskey, and the Stop'n'Go, 7-11, Circle K, whatever name on that one corner, in that one place, where someone calls the intersection of a convenience store and a gas station their town, their home, their grass. Paint or aluminum siding. A kitchen and carpet. Photos of Aunt Edna and Uncle Charlie. That summer Chuck went for a ride on a Harley under redwoods and past cool stream shadows while Julie, as little girl, slept in a Ford station wagon. Faded blue. Wood paneling peeling open to rust. The back flipped down for her and Ursa Major poured out sky. * In Nicaragua the colors are electric water in air. The weight of clouds on winged cockroaches and crocodiles in streams. La Virgen de Guadalupe. My cousin, Maria Guadalupe Sanchez, on a bike with Brenda through a suburb of Managua on the handlebars. The streets were Miguel, her brother, with a rifle shooting iguanas from a tree in a pickup or Jeep. The huge overbearing green of myriad plants inching their way past monkeys and chickens to a patio whitewashed and cool. The distance away from grandmother. Actually great-grandmother and her son, the witch doctor who could stop malaria with powder or a gaze into trembling hearts. The known ancient crossing to psychology, biology, chemistry. The workings of ourselves. A railroad blasted through mountain. * I want to dance during the Verbenas. I don't know the word or correct spelling. V or a B? Just a sound from a one-time visit to Nicaragua. A celebration. A truck lined with palm fronds in a parade, then dancing. At three in the morning, it was still warm. Verbenas. An old colonial colonel's name? A street? A time to celebrate the harvest of bananas, yucca, corn, beans? I don't know. There was a monkey on a leash, on the roof. The tiles curved from Tía Teresa and Tío Rafael to me being pretty sitting at a table with my first rum and coke. The loss of my virginity was to be a golden icon mined from history where my grandfather was a child hidden under a loose brown skirt and delivered to a convent. Mi abuelita with her eight kids. My aunts and uncles. My mother with us. In college with Philip, a boy standing naked looking out a window, his butt prettier than mine, it was California. There were palm trees. I was correctly 18. I had gone to visit Planned Parenthood. The ladies behind a desk were asking questions and taking notes. With a brown paper bag I waited on grass, in the park, knowing already Interstate 80 divides this nation in two, beginning in San Francisco cutting straight through to New Jersey on the Atlantic Coast. IN CONVERSATION: ADELA NAJARRO (AN) AND LUCHA CORPI (LC)

LC: Adela, I have enjoyed listening to you read some of your poems a few times. Mostly, when we happened to coincide at meetings and readings sponsored by Escritores del nuevo sol in Sacramento and Círculo de poetas and Writers in Oakland. It’s been a treat every time. But quite a double and triple treat now to read and reread your exquisite poetry in solitude, as I prepare for our charla here today. And I am in awe, not just for this pleasure of hearing and reading your poetry. I have also had the opportunity to see you organize public events with an ease that never ceases to amaze me. Also because reading your biographical material I realize that you are a wife, mother, indefatigable professor, community organizer, a “dynamo” poet… and so much more. Above, in your biographical information of your early years, you close your narrative with a line that immediately held my attention: “I write to understand my place in the world.” Could you elaborate? AN: That arises from the idea that poetry is discovery. A rant, a diatribe, a polemic , all make statements about what is already known. The rant is yelling, screaming, crying on the page over events that have happened; the diatribe is an attack; the polemic tries to convince through astute argument. All of these begin from a standpoint of knowing, knowing how one has been wronged, knowing the wrong itself, and knowing how to correct and proceed. That’s not poetry. Poetry has to begin with an open mind that follows language into a discovery or truth. It is through writing that I discover the truth of what surrounds me, in the past, the present, and even in the future; in that sense I come to understand my place in the world. I have no fear. If the truth I find is one of betrayal, hatred, violence, anger, then that is a part of the world I live in. Even so, it surprises me over and over, how writing always takes me to hope. Even when I write about issues that have broken others or myself, I always find beauty. Maybe it’s about being alive, being able to breathe, being able to wake up one more day. Praise God and sing Hallelujah! Poetry and religion merge onto the same roadway in that they both seek the human spirit and lead us to compassion, again, our place in the world. LC: In “Redlands, California,” you tell the story of living in the United States while imaging life in Nicaragua. Could you talk about the context you had in mind when you imagine a homeland, Nicaragua, that you don’t know since you grew up in the United States? AN: My brain developed a duality of language and culture as I grew up. I learned English in pre-school while my first language was Spanish. I was living in U.S. Anglo culture while at home it was all about Nicaragua. So—"Los dos fit better than one alone.” That’s my line from “Conversation with Rubén Darío's ‘Eco y yo’,” which was first published in Nimrod International Journal of Poetry & Prose and appears in my collection, Twice Told Over. Los dos. I view myself in terms of Whitman and Anzaldúa in that I contain multitudes in my mestizaje. I seek an American literary tradition that contains the Anglo, the male, the Latinx, female, and all the range between. There is no set answer, just the flux of words, our thoughts, the daily wakening to a new day that somehow seems old and familiar. “Redlands, California,” has three sections, the first is about life in the States; in the second, I imagine life in Nicaragua; the final section tries to create a new juxtaposition between these two states of being, and, of course, it ties in with sex because what else captures the union of two distinct bodies? The Nicaragua I know is the Nicaragua of my imagination and that of the stories told by my parents, abuelitas, cousins, tías y tíos. I tell and retell their stories to bring them into the literary conversation of the Americas. They matter. They are part of the American story. As a writer it falls to me to create poems that capture this duality of language, culture, immigration, las penas and the joy. LC: Tell us what you will about your creative process. Do you sit down to write at certain times of the day on certain days? What happens if you get inspired while driving or in other similar situations? Do you memorize the lines for the time you finally write the poem where they belong? Or hope for the best? AN: There was a time when I wrote nearly non-stop. I remember being at a job training and writing a poem. I have written poems on napkins. I have written using big orange markers. I feared that if I stopped writing, then the Muse or inspiration would vanish. But it never has. As I accepted that writing was part of my identity, of who I am, and what makes Adela, Adela, I took a couple of days off. Then I wrote about those days. Then I took a few more days off, then wrote new poems. Eventually, I realized that my mind collects ideas, images, language, every waking and sleeping moment. When I sit down to write, it comes out. Then the work becomes revision. Editing. Cutting that which doesn’t belong and expanding that which is hidden, all the while finding the exact words and rhythms. Doesn’t that sound like joy? It is to me. When I write, I am at one with everything. I accept whatever shows up. The pain, the horror, the laughter, the jokes, the image. Right now there is an owl in the eucalyptus tree outside my bedroom patio. Earlier coyotes were howling at sirens, not the moon, but sirens. Someone on their way to a hospital. Tomorrow, a mint leaf will open in a pot. There are spiders in the eaves. Every waking moment holds something and then the world of dreams, the imagination, the possibilities. Here are the final lines to “Conversation with Rubén Darío's ‘Eco y yo’”: Out of the delirium, the sweat, the anxiety of every morning, we weave a soft and tender sea, the mermaids, the song, the possibility, and all begins again. *** Thank you Lucha for this conversation. It is always such a pleasure to see you and collaborate! Hasta la proxíma. Mil gracias, Adela. © Adela Najarro: the poems that appear in this interview are from Twice Told Over, published by Unsolicited Press, 2015, with permission of the author. More information about Adela can be found at her website: www.adelanajarro.com. NICOLE NOEL HENARES THE POET: A PERSONAL NARRATIVE I was born in the Monterey peninsula, California, in August, 1974. I proudly share the same birth date as the great labor activist and guerrillera cultural, Luisa Moreno, who organized the women of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, my grandmother’s labor union. My grandparents and their families were members of the immigrant communities who worked on Cannery Row between the 1920’s and 1930’s in the Monterey Bay Area, California. After the collapse of the sardine canning eras in the 1950’s, my grandfather taught himself carpentry. Although it took him three times to pass the test, he became a general contractor. He was very proud of achieving his goal, as he did so without having any formal education. All my cousins and I celebrated our birthdays at the Carousel in the old Edgewater Packing Company on Cannery Row. My fascination with Cannery Row and my family history began then. I started school when I was five years old. I went to Marina Del Mar elementary school. Marina del Mar was a bedroom community of Fort Ord, the largest military base on the west Coast at that time. My mother was a teacher at the school I attended, and piloted one of the first multicultural education curriculums in the country under the tutelage of Dr. Charlie Knight, the first black superintendent of Monterey Peninsula Unified School District. I read a poem when I was five years old. It was about strawberries and fairies. I felt inspired by the fairy book of poems I read then. But I didn’t write my first poem until I was seven. Every time I wrote poems I felt exalted. At the time, I wrote about many other subjects. But I loved writing about fairies. I was really into fairies. I attended a predominantly white high school, in the city of Carmel, located near the city of Monterey. My high school English teacher was Ms. Gilbert--who is now Señora Quintanilla. It was in her classes, during my sophomore year, that we started discussing themes of race and gender. She had us reading everything from Chaim Potok to Lorraine Hansberry and Ray Bradbury. My favorite subjects were English, History and, French. I’m ashamed to admit that I took French and not Spanish to spite my father, because he used to tease me so much, telling me that I spoke Spanish like a gringa. I was very shy around boys and didn’t feel safe around them until I was in high school. But I did have a lot of friends who helped me get through my freshman year. When I was in the ninth grade I was lucky to be mentored by a Latina student who was a senior. She advised me not to compare myself to the white girls. To be myself. She is now Dr. Lauren Padilla-Valverte, the head of the California Community Foundation. The most memorable event in my life before age 18 was playing the Vivaldi violin concerto at the Spring Concert in 1989, my sophomore year, and getting straight A’s except for a B in math. I hated Math. I was 14. Along with a B in Math, I got a D- in Health because pretended to sleep during Sex ED. I was very uncomfortable in that class - I'm a survivor of early childhood sexual abuse. In high school my friends and I were being groomed and molested by an older man we knew at the skating rink. Many of my girlfriends at that time were also victims of what we would call now intimate partner violence. It all bothered me. I didn't know how to talk about anything so I pretended to sleep. The teacher threw erasers at me, but ended up telling my mom I was a "good kid" he just didn't understand what was wrong. Even in my poems from that time, I chose to focus on the resilience within love and connection for the world around me, rather than the pain. However, to fully understand our resilience the trauma it comes from needs to be acknowledged. THE POETRY They say the fourth plane that morning was heading here: 5pm Lonely brass frog statues and armed barricades surround the Trans-America Pyramid, glowing up Columbus Avenue to lime and cherry chipped neon where strip club barkers idle: Tonight, only the regular horny wander in, a hunchbacked Cornell educated former engineer, now poet, with rainbow suspenders, a skin condition, and Mork from Ork hair, needing some semblance of normalcy in a stripper named Scout. Faithful restaurants hesitantly remain open but empty; rows of tables, garlic, pannini, and chianti wait for customers who never come. 7pm The streets are still, like Easter morning, except, instead of church the people hide in the temple of FOX, CNN, and ABC news, praying the dead find resurrection while polychromatic screens synthesize background music, instant replays and red blocked letters AMERICA UNDER ATTACK. In the bar with the photos of naked, now dead, beat poets holding peace signs & flowers, a gaggle of workers from the financial district dissolve around the television that hovers morning into night. One stockbroker, his hair a perfect wave, who says his friends worked in the Towers, loudly slurs through curled lips, “I hope we bomb them, bomb them all, even the young, before they’re old enough to kill..” The bartender shaky with white knuckles, wants to reply but the day has been slow and she needs the tip. 9:30 pm In another bar, one of the only in North Beach without a television, an overly hormonal tranny torch singer, an English teacher, and a piano player named Sam-I-Am share a basket of Danish cheese and crackers, while arguing over the spelling of Afghanistan and the logic that Grendel killed the Danes just because he was “evil”. They wait for James, who’s full of Wizard of Oz masonic conspiracy theories, complaints about backwards baseball caps and the price of hot-dogs, to hear what he’s gonna say. 11pm Wearing wrinkled pinstripes, two young blues musicians play guitar in an alley with Lightnin’ Hopkins’ vengeance- They never say a word about the tempo, terrorists, or vapid late summer night. If John Lee Hooker’s holy Crawlin’ Kingsnake, or a big legged woman slithered next to them they’d only butter from 12 to 7 bar blues. One of them has suffered heroin, baby mama drama, and recently five days in the drunk tank. The other, on vacation from Finland, has lost his wallet, passport, and two guitars in three months. Every blues is their blues; through the night in doorways with purple and green mardi gras beads, lousy tarps and bottles of Hennessey to keep them warm. 2004 Thou Mayest THIS IS THE BREAD OF THE CHOSEN THIS IS THE FOOD OF THE ACCURSED we are a culture of beernuts/ fox sports/ major league/ too much/ shopping/ when the going gets rough/ towers are bombed/ the tough are encouraged/ to consume/ Keep America Open For Business/ one night stands and three marriages moralistic lies /a smoke and mirrors of values and greed/ spooning chainsaws jetskies NASCAR gasoline/ racing / buy one pie get the second for free we are a nation of flatulence go team go faster bigger MORE where the package is more interesting than the toy it’s a cataclysm of the heart a wanton sickness cheap words and extravagant catcalls placing me head first into the bellies of vases/legs flying out/ heart shaped orchid exposed/ only for/ a copulating squawk as the coin twists in the air the shock of the bourgeoisie/ the self proclaimed café hip/ just another commodity for sale/ thinking poetry is bread of the enlightened/ the chosen so smug in hip righteousness/words pockmarked in cheap jewels & artificial fruity blossoms this is the food of the accursed/ the morsels of the damned/ the kernels of those/ who are nothing/ but a statistic to throw around in coffee shops/ a girl who has seen more death at sixteen/ than anyone should/ she told me she couldn’t even recognize his face because it was so covered in blood when he was shot after school on the 29 MUNI and she lives here/ in this city/ in our backyard the slaughter continues /another kid in a coffin we’re not allowed to see/ another imprisoned /headlines just hyper-reality television/ while others like them fight and torture in foreign lands and in our glittering high-rises the twins dance tangerine waltzes /acerbic hipsters syncopate f# on the half note/sip pinot grigio spritzers/ sway with venetian glass eggs up their stoned asses/ point that’s so bourgeois / in between troubled time signatures/ and watery coughs from next-door yet it is the same melancholic tune at 2 am/ babies in cradles of filth/ momma just a baby raised by the television/ so come and see come and see DO YOU SEE I am a deformation for the cursed I snore variations composed on laughter with my cape on and kitchen utensil corsage dirging sonorous nonsense / as a meal my mouth is filled with muddied jellied flowers juggling soured waters pustulled clocks gnawing on the husks of time between my black sounds /the death among the bougainvillea/ live giant balloons/ and hummingbird springs pale stalks of corn /blackberries/ without brambles/ snapped open fuchsia blossoms /releasing nectar for the bleeding while the arrogant wear their spoils I swallow poetry as a prayer 2004 The Dance Of The Urban Honeybee for Ric Masten I needed to mail a letter so I go to my corner Walgreen’s and purchase 4 stamps for $1.99... Later, when the 48 cent difference occurs to me, I wonder if I paid extra for the red cursive emblemed cardboard and plastic wrapping, or convenience? Yesterday I saw a man yell at hotel strikers- workers of less than $10/hour, locked out for demanding health benefits. The man said the strikers made too much noise" "Shut the fuck up!" "Shut the fuck up!" They call me teacher, poet, guide; the honeybee sent out to find a new destination where the hive can find safety. Yet, I'm finding no answers; my students think I'm crazy, too tough of a grader, there's a hole in the ceiling of my classroom, and the heater doesn't work. On the streets, panhandlers stand on their heads next to marquis that say, "All you could ever want to eat". While, Bitsey, the heroin addict midget prostitute crutches across Market Street her freshly amputated left stump swinging in rhythm with the swoosh of traffic. And what's most sad is that it is all so familiar. So I dance my hallucinatory jig that's supposed to tell, "this is where we go from here" to a vacant hive of no answers just a solitary moan of panicked despair. 2004 The Downcast Dreamer Tonight in this limpid ball it's just me and the alleyway mourning doves saying to hell with it all. I surround myself in miniature ornamental beauty because it’s easier to live in the watery glitter of a snow-globe than search for the ineffable in the perfume of the city’s rust and dream white laced with sorrow and the ash of rage. I'm turning mermaid and a bit sea-witch, my heart with the sexless ocean, shiny hard and gaudy, while the doves get drunk like pigeons and hoot tintinnabulations of angels and soundless blessings to empty arms. 2005 Comfort Of The Dead I dreamt of the dead last night, for the second time this week. It was a most rare vision, perhaps past the wit of man to say what dream it was. We were at a play that was being performed in a big auditorium with red, white and blue seats. He had arrived early. He wasn’t high, he didn’t even have a beer with him. He had arrived early, and was waiting for me. He even saved me a seat. The show was sold out. It was a performance of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice - (Once upon a time, he ground scored an entire pocket book collection of Shakespeare for me because he knew that I loved Shakespeare.) I was running late, in self pity and despair. Then the realization set in- Yes, our country had elected a president, but he was still alive. He never had died. He was alive and he was waiting for me in an auditorium where we were going to watch a performance of A Merchant of Venice. Some of my students were in the lobby handing out programs. I panicked to find my seat. He wasn’t angry, he held my hand and whispered in my ear that of course he would hold a seat for me, he would always hold a seat for me. He said all that he said when he was alive- That his white last name did not matter, he would always be proud of his brown skin. It did not matter what the historians could or could not dig up, his family had been here since before there were borders, before this was even a state, and was just a place with a made up name. “First we were generals and governors, then we were bad hombres: All that glitters isn’t gold, the quality of our mercy is very fucking strained, and why shouldn’t it be?” The only thing that had changed, was that he no longer said anything about his punk rock nihilism, or wanting to watch the world burn. The only thing he said he wanted to do was watch that play. And as the curtain rose, he whispered, “The poem’s the thing to love for eternity.” 2016 Then And Now “If the problem with PTSD is disassociation the goal of treatment would be association- integrating the cut off elements of the trauma into the ongoing narrative of life, so that the brain can recognize that ‘that was then, and this is now.’” BESSEL VAN DER KOLK Now that I have remembered I can never forget the tick of your heart against my cheek in cold and time travel and fog. your caution knew me and hung in my mouth. You were in trouble, needed to leave, but wanted to say, I didn’t need to marry a poet to be a poet confessions stitched my griefs into silence. I knew you too. You were water and mirror my body remembers in rhythms and strange dreams haunt me. Dreams of the dead and regret when I am sitting in a vat of truth addicted to the taste of illusion and shadow, my greedy skin like dragon scales all sense of myself made no sense. So I scratched and scratched until my fingernails dug beyond flesh, beyond longing, until there was nothing left but blood and bone, and the stubbed beginnings of great green feathers. Happiness is more than earthly delights. (There is only so much sadness allowed.) The poems synthesize, enter a temple of prayer. My words tell me things: Conjoin clever rhymes find coyness within symbols that never dissolve like eighth notes carved into mountains. Chimeras are imperishable and can mother beauty. Forget the intoxication of anger and fear and rot Now is winter in my kitchen. Now is earth and my ear pressed to chest after washed dishes, thank you falls from lips. Now is spring and cusp, bending down onto knees and teasing my cat with a bright pink feather attached to a stick. Now is entwined fingers speeding along the blur of blacks and golds on a nighttime bridge of lights amid pandemic and awakening. EL POEMA es la erección del ahorcado. Demasiado tarde y para nadie. Pero ahí. -David Eloy Rodriguez I Will Wear Yellow Te quiero, entiendes? I will wear yellow. Estas palabras son las palabras de mi sangre, y mi alma, entiendes? No entiendo como tú eres como eres. No entiendo nada, ni el por qué devoras mi corazón, mi cuerpo, mi cabeza, y mis ojos. No entiendo nada, sólo que te quiero. No entiendo nada más. Te quiero. I will wear yellow because I am always trying to find light. Every night the sunset echoes from behind the trees. I remain a heart in the green of mourning. But I will wear yellow. Tonight I am with the waning moon who hovers over the world with her ever changing face. I have listened closely to the secrets the past has told. Don’t worry so much about the future- only the differences between intention and expectation. The oranges are beginning to appear again, and in May the jacaranda will bloom electric and purple. There is always the possibility of starvation and catastrophe and ego and war, but, even then, there is the humble magic of licorice and I know how to find it. Sometimes I hear pointing, accusatory silences, and the sunset continues to cry louder and louder with the click of time. I will wear brass hoops around my ears and around my wrists. I will fall into water. I will wear yellow. All lovebirds are mourning doves. They know my sorrow, like you know my sorrow, and have poured salt and pepper into these wounds, reminding me to look for light as my words turn into the echoes of ragged claws scuttling across the ocean floor, and I dress my heart in yellow. 2020 IN CONVERSATION: Lucha Corpi (LC) and Nicole Noel Henares (NNH) LC: While I’m reading your wonderful poems, Nicole, I’m searching for the reason I haven’t been back to San Francisco just to sightsee on a May or October Sunday afternoon in such a long time. Living in Oakland and crossing the Bay Bridge wasn’t a big deal those Sundays, long ago. The bumper to bumper traffic on the Bay Bridge has become a deterrent now. And I am much older, too. Back then, I always loved driving my young son Arturo and me places, especially on Sundays. Driving by North Beach on our way to Fisherman’s Wharf on my VW Beetle—the Volchi. Taking a deep breath and pushing with my soul and stomach to inch up to the top of Nob Hill hills, fearing that the engine would stall and ... It never happened. After, we’d make our way back to The Mission to savor a fabulous and, at the time, inexpensive meal at a Central American, South American or Mexican Restaurant. Later, after Arturo left home, every so often I would meet Francisco X. Alarcón, Juan Felipe Herrera, Víctor Martínez, Elba Sánchez, Odilia Galván Rodríguez, Rogelio Reyes, Juan Pablo Gutiérrez and other writers of Centro Chicano de Escritores there and have a good time catching up, reading our new poems to one another, and laughing a lot. Enough reminiscing. Let’s talk about you. ****** LC: Nicole, did you live in San Francisco’s North Beach at the time you wrote these poems? When? Why? NNH: From 2001-2013 I lived in Lower Nob Hill about a fifteen minute walk from near North Beach. I gravitated to that neighborhood because of its history with the Beats. LC: How were those years different from your life in Monterey and your painful experiences in Carmel as you were growing up? NNH: In 2001, after 9-11, everything was surreal in the ways it wasn’t surreal. In August 2001 one of my closest friends had OD’d on heroin and had to be identified by his dental records. Two months after 9-11, my godbrother was killed in a drug related murder. There was something familiar about all the chaos. It was easier to make sense out of the political chaos than my personal chaos, but I realize how much both were interconnected. In 2001 I started keeping a notebook again because I had moved to San Francisco to teach and to write. But I had always been writing intermittently throughout my life and expressed political views. I started keeping a diary in 1981 when I was five years old. My first diary entry was, “The hostages were released today, poor Jimmy Carter.” LC: Did writing poetry offer you a way to deal with the unmitigated pain, “the green of mourning”? NNH: The “green of mourning” was about the series of violent deaths I experienced in 2001, including all the deaths in 9-11 . The “green of mourning” circles also the edge of the wound of lost childhood. Compassion means to suffer with and to celebrate. Even as a child, writing was a way to find self compassion, and compassion for the world around me amid the effects of childhood sexual abuse. Though it is never directly stated, it is always there as a subtext. I love my family. Both of my parents were community activists, trying to do the best they could. The adult son of one of my grandmother’s cousins had been molesting me for years—it began when I was three years old, and went on until I was six. He was very disturbed. After my grandmother died and my grandfather remarried, this cousin defaced my grandmother’s grave and sent crazy letters to the house in cut and paste letters. I never talked about any of these things because I felt doing so would somehow betray my family. Only recently in facing these memories did I begin to remember how much my parents suspected but never knew what had happened much less how long it had been happening. When my father found out something was going on he said something to the cousin in English explicitly so I could understand. Part of the terror in facing this trauma is that it happened in a different language. I am still struggling how to allow my resilience to define me more than my trauma. Part of that I think has been speaking Spanish again, and falling in love with the Spanish language, as well as symbols of my childhood that were part of my resilience—like fairies, strawberries, and unicorns. LC: There’s a line in your poem “Now And Then”: “I didn’t need to marry a poet to be a poet.” When I read it, I wasn’t sure whether the lover or the poet was saying it. I suppose it could be an interchangeable line, when the end of a relationship is clear to both. Could you elaborate? NNH: I got engaged to my first husband within two weeks of knowing him. He was/is a great poet. But at that time I didn’t consider myself a poet. I put him on a pedestal as “the poet.” The person who said this to me knew me well enough to call me on my bullshit. LC: Nowadays, what makes you happy? Angry? What springs feed your creative streams?