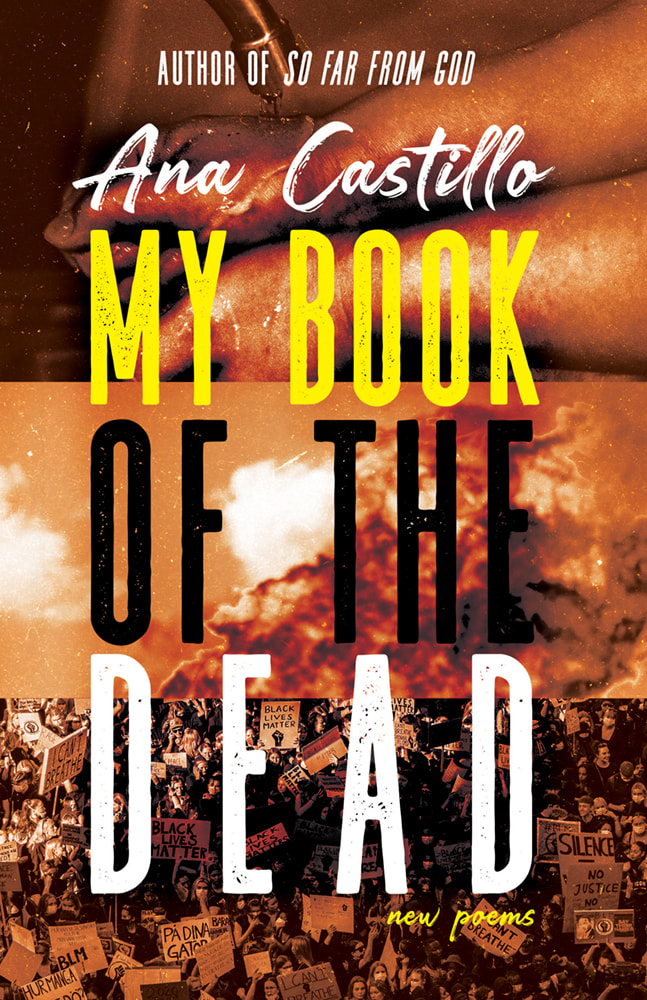

An Excerpt of Ana Castillo's My Book of the DeadThese Times In these times, you and I share, amid air you and I breathe, and opposition we meet, we take inspiration from day to day thriving. The sacred conch shell calls us, drums beat, prayers send up; aromatic smoke of the pipe is our pledge to the gods. An all-night fire vigil burns where we may consume the cactus messenger of the Huichol and of the Pueblo people of New Mexico. Red seeds of the Tlaxcalteca, mushrooms of María Sabina, tes de mi abuela from herbs grown in coffee cans on a Chicago back porch, tears of my mother on an assembly line in Lincolnwood, Illinois, aid us in calling upon memory, in these times. In other days, when memory was as unshakeable as the African continent and long as Quetzalcoátl’s tail in the underworld, whipping against demons, drawing blood, potent as Coatlicue’s two-serpent face and necklace of hearts and hands (to remind us of our much-required sacrifices for the sake of the whole). We did what we could to take memory like a belt chain around the waist to pull off, to beat an enemy. But now, in these times of chaos and unprecedented greed, when disrupted elements are disregarded, earth lashes back like the trickster Tezcatlipoca, without forgiveness if we won’t turn around, start again, say aloud: This was a mistake. We have done the earth wrong and we will make our planet a holy place, again. I can, with my two hands, palpitating heart; we can, and we will turn it around, if only we choose. In these times, all is not lost, nothing forever gone, tho’ you may rightly think them a disgrace. Surely hope has not abandoned our souls, even chance may be on our side. There are women and men, after all, young and not so young anymore, tired but tenacious, mothers and fathers, teachers and those who heal and do not know that they are healers, and those who are learning for the sole purpose of returning what they know. Also, among us are many who flounder and fall; they will be helped up by we who stumble forward. All of these and others must remember. We will not be eradicated, degraded, and made irrelevant, not for a decade or even a day. Not for six thousand years have we been here, but millions. Look at me. I am alive and stand before you, unashamed despite endless provocations railed against an aging woman. My breasts, withered from once giving suckle and, as of late, the hideousness of cancer, hair gone grey, and with a womb like a picked fig left to dry in the sun; so, my worth is gone, they say. My value in the workplace, also dwindled, as, too, the indispensable role of mother. As grandmother I am not an asset in these times but am held against all that is new and fresh. Nevertheless, I stand before you; dignity is my scepter. I did not make the mess we accept in this house. When the party is done, the last captive hung—fairly or unjustly-- children saved and others lost, the last of men’s wars declared, trade deals busted and others hardly begun, tyrants toppled, presidents deposed, police restrained or given full reign upon the public, and we don’t know where to run on a day the sun rose and fell and the moon took its seat in the sky, I will have remained the woman who stayed behind to clean up. From My Book of the Dead by Ana Castillo © 2021 by Ana Castillo. Courtesy of High Road Books, an imprint of the University of New Mexico Press. My Book of the Dead I They say in the Underworld one wanders through a perennial winter, an Iceland of adversity. Some end in Hades, consumed by ¨res that Christians and Pagans both abhor. <#> My ancestors too imagined a journey that mirrored Earth. Nine corridors-- each more dreadful than the one before-- promised paradise. You kept your soul but not your skin. II When my time came to return to the womb, I wasn’t ready. Anti-depressants, sex, a trip, prize, company of friends, love under moonlight or generous consumption of wine-- nothing did the trick to ease my mind. When the best, which is to say, the worst rose from swamp, elected to lead the nation-- I presumed my death was imminent. Eyes and ears absorbed from the media what shouldn’t have been. Had I time traveled back to 1933? Perhaps I’d only woken to a bad dream, or died and this was, in fact, Purgatory-- (Did being dead mean you never died?) The new president and appointed cabinet soon grabbed royal seats happy as proverbial rats in cheese. An era of calamity would follow. Holy books and history had it written. ¦e Book of Wisdom, for example, spoke of the wicked rollicking down the road, robbing the in¨rmed and the old. ¦ey mocked the crippled and dark skinned-- anyone presumed weak or vulnerable. Election Night-- I was alone but for the dog, moon obscured by nebulous skies; sixty-odd years of mettle like buoy armbands kept me afloat. Nothing lasts forever, I’d thought. Two years passed, world harnessed by whims of the one per cent. I managed-- me and the dog, me and the clouds, contaminated waters, and unbreathable air-- to move, albeit slowly, as if through sludge, pain in every joint and muscle. Sad to behold, equally saddened of heart, and still we marched. III Sun came up and set. Up and down, again. My throbbing head turned ball of iron. Thoughts fought like feral cats. Nothing made sense. The trek felt endless, crossing blood rivers infested with scorpions, lost in caverns, squeaking bats echoed, µying past, wings hit my waving hands. I climbed jutting flint, bled like a perforated pig, ploughed through snow-driven sierra, half-frozen—lost gravity, swirled high, hit ground hard. Survived, forged on. Two mountains clashed like charging bulls. Few of us made it through. (Ancestors’ predictions told how the Sixth Sun would unfold with hurricanes, blazes, earthquakes, & the many that catastrophes would leave in their wake.) IV (Demons yet abound, belching havoc and distress. Tens of thousands blown by gales of disgrace.) V (I hold steadfast.) VI ca. 1991 The Berlin Wall was coming down. One afternoon beneath gleaming skies of Bremen, Dieter was dying (exposure to asbestos in his youth). “My only lament in dying would be losing memory,” my friend said. “All whom I knew and all whom I loved will be gone.” Once a Marxist, after cancer—reformed Lutheran. (It was a guess what Rapture would bring a man with such convictions.) A boy during third Reich, Dieter chose to safekeep recollec- tions—from the smells of his mother’s kitchen to the streets of Berlin that reeked of rotting flesh as a boy. Men had always killed men, he concluded, raped women, bayoneted their bellies and torn out the unborn, stolen children, stomped infants’ heads, commit- ted unspeakable acts for the sake of the win, occupy land, exact revenge, glory for the sake of a day in the sun. (Do the dead forget us? I ask with the lengthening of days each spring. Do they laugh at our naïveté, long for what they left behind? Or do they wisely march ahead, unfazed?) VII Xibalba (Ximoayan & Mictlán & Niflheim, where Dieter rightly should have gone) cleansed human transgressions with hideous punishments. You drank piss, swallowed excrement, and walked upside down. Fire was involved at every turn. Most torturous of all, you did not see God. Nine hazards, nine mortal dangers for the immortal, nine missed menstruations while in the womb that had created you-- it took four years to get to heaven after death. Xibalba is a place of fears, starvation, disease, and even death after death. A mother wails (not Antcleia or la Llorona but a goddess). “Oh, my poor children,” Coatlicue laments. Small skulls dance in the air. Demon lords plot against the heavens I wake in Xibalba. Although sun is bright and soft desert rain feels soothing, fiends remain in charge. They take away food, peace of any kind, pollute lakes, water in which to bathe or drink, capture infants, annihilate animals in the wild. (These incubi and succubi come in your sleep, leave you dry as a fig fallen on the ground.) VIII There were exceptions to avoid the Nine Hells. Women who died giving birth to a future warrior became hummingbirds dancing in sunlight. Children went directly to the Goddess of Love who cradled them each night. Those who drowned or died of disease, struck by lightning or born for the task, became rainmakers-- my destiny—written in the stars. Then, by fluke or fate, I ended underground before Ehecátl with a bottomless bag of wind that blew me back to Earth. IX Entering the first heaven, every twenty-eight days the moon and I met. When I went to the second, four hundred sister stars were eaten by our brother, the sun. Immediately he spit them out, one by one, until the sky was ¨lled again. In the third, sun carried me west. In the fourth, to rest. I sat near Venus, red as a blood orange. In the fifth, comets soared. Sixth and seventh heavens were magni¨cent shades of blue. Days and nights without end became variations of black. Most wondrously, God dwelled there, a god of two heads, female and male, pulled out arrows that pierced skin on my trek. “Rainmakers belong to us,” the dual god spoke, his-her hand as gentle as his-her voice was harsh. Realizing I was alive I trembled. “You have much to do,” he-she directed. Long before on Earth a Tlaxcaltec healer of great renown crowned me granicera, placed bolts of lightning in my pouch. I walked the red road. Then came the venom and the rise of demons like jaguars devouring human hearts. They brought drought, tornados, earthquakes, and hurricanes-- every kind of loss and pain. The chaos caused confusion, ignorance became a blight. (Instead of left, I’d turned right, believed it day when it was night. I voyaged south or maybe north through in¨nity, wept obsidian tears before the dual god-- “Send me back, please,” I cried. “My dear ones mourn me.”) X The Plumed Serpent’s conch blew, a swarm of bees µew out from the shell. Angels broke giant pots that sounded like thunder. Gods caused all manner of distraction so that I might descend without danger. Hastily, I tread along cliffs, mountain paths, past goat herds and languishing cows. A small dog kept up as we followed the magenta ribbons of dawn. I rode a mule at one point, glided like a feather in air at another, ever drifting toward my son, the granddaughter of copper hair, sound of a pounding drum-- we found you there, my love, waiting by the shore, our return. From My Book of the Dead: New Poems by Ana Castillo © 2021 Ana Castillo. Excerpt courtesy of High Road Books, an imprint of the University of New Mexico Press. Buy a copy from the publisher here.  Ana Castillo is a celebrated author of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and drama. Among her award-winning books are So Far from God: A Novel; The Mixquiahuala Letters; Black Dove: Mamá, Mi’jo, and Me; The Guardians: A Novel; Peel My Love Like an Onion: A Novel; Sapogonia; and Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma (UNM Press). Born and raised in Chicago, Castillo resides in southern New Mexico.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Donate and Make Literature Happen

is published by the Somos En Escrito Literary Foundation,

a 501 (c) (3) non-profit, tax-exempt corporation. EIN 81-3162209

RSS Feed

RSS Feed